The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Water

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Water

The [media]need for a source of clean water is arguably the reason why Sydney was founded where it is today. When the First Fleet approached the coast off what is now Sydney in January 1788, their initial explorations took them to Botany Bay, where they anchored for several days. Of that initial landing in Botany Bay, Governor Arthur Phillip observed:

Several small runs of fresh water were found in different parts of the bay, but I did not see any situation to which there was not some very strong objection…Several good situations offered for a small number of people, but none that appeared calculated for our numbers. [1]

On 24 January 1788 Lieutenant William Bradley of the Sirius reported that Phillip had returned from an exploratory expedition into Port Jackson,

having discovered Port Jackson to be an exceeding [sic] fine Harbour with many coves all forming Inner Harbours, the soils far preferable to that at Botany Bay & in some parts a good soil & well supplied with water. [2]

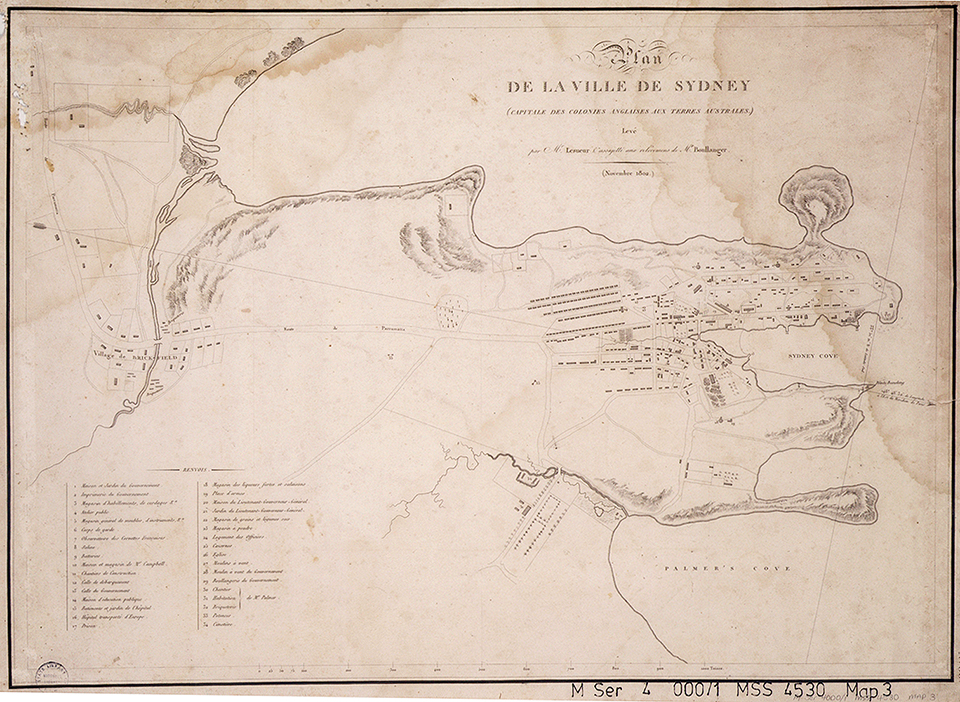

[media]Following Phillip's discovery of a good source of fresh water, the Fleet moved into Port Jackson before anchoring at what became known as Sydney Cove, attracted by both the good harbour and the stream running through the mudflats and out into the cove. Such an apparently reliable source of water would have been a boon for the Fleet, which had been subject to water rationing throughout the voyage from England. [3]

The early settlement straddled this as-yet-unnamed watercourse, with the Governor's house and the government farm located to the east and the other buildings of the colony – including barracks for both prisoners and soldiers – located to the west. [4] In addition to being a source of water, the stream became a line of social demarcation and administrative control. By 1792 this arrangement had shifted, with the soldier's huts still west of the stream and the prisoners' barracks moved to the east, closer to the government workshops and farm. [5]

The Tank Stream – the first water supply

[media]Water quickly became an issue for the young city, with the stream proving to be rather more intermittent than originally thought and, as the settlement grew, drinking water was supplemented with wells and cisterns. Contemporary observers, such as Captain Watkin Tench, noted that the new colony had considerable difficulty in sourcing sufficient fresh water, [6] and as early as February 1788 Bradley had noted that the streams feeding the early colony would run dry in hot weather. [7]

This central watercourse was supplied from a catchment which started near present-day Hyde Park and included most of what is now the central business district. By 1790 work had been undertaken to smooth the stone bed of the stream to improve its flow, and to cut tanks into the rock on either side of the stream for the storage of water, giving the stream its name. [8]

The encroachment of the settlement upon the stream, known by then as the Tank Stream, also became an issue for the early colony. Governor John Hunter issued an order to the colony on 22 October 1795 that

any person found using a path from the house to the [Tank S]tream, or keeping hogs in the neighbourhood thereof…will be removed, and the house pulled down. [9]

Hunter repeated this order in January 1796 but his efforts were ultimately unsuccessful in keeping the Tank Stream from becoming little more than an open sewer by the end of the eighteenth century. In October 1803, the government made an effort to clean out and restrict access to the stream; [10] however a further notice regarding the penalties for polluting the stream was published in the Sydney Gazette on 18 December 1803, and again reiterated in an order of Governor Macquarie on 8 February 1810. [11] The problem of pollution had become an endemic one, and its prevention was ultimately a losing battle for the colonial government. Other sources of water had to be found.

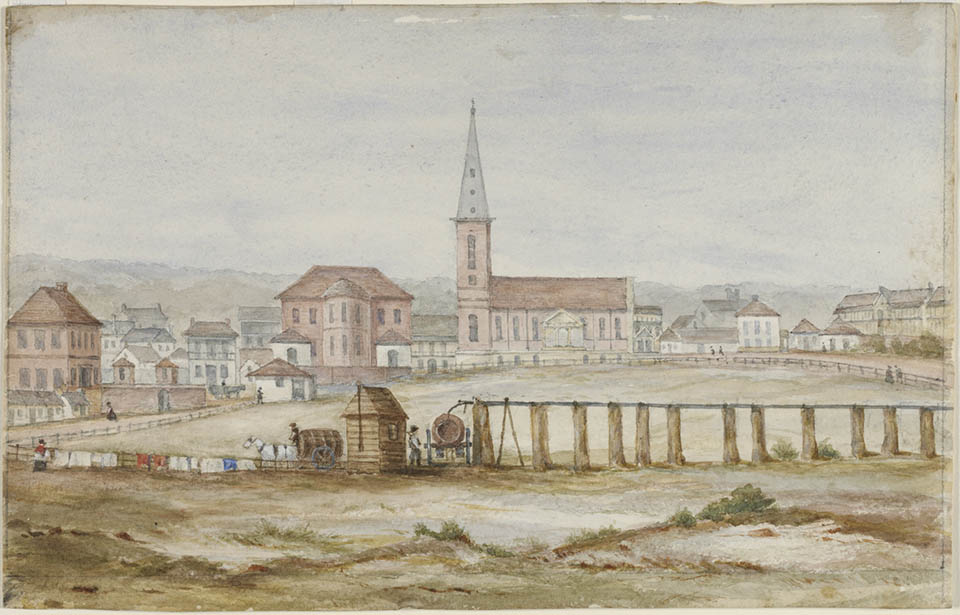

[media]As the city grew and the Tank Stream began to fail as a source of water, wells were dug in various places. Major public wells with pumps were located in several places in the centre of the city, as well as at Haymarket, in Paddington near Victoria Barracks, at Queen's Wharf, at the Park Street entrance to Hyde Park, opposite Darlinghurst Court House and at other locations. [12] In the 1840s, control of the pumps was leased out, with the lessee having the right to sell water to the public.

[media]While it remained an open watercourse for nearly another four decades, the Tank Stream had become merely an open sewer and was progressively enclosed in stone and brick from 1860. Today, sections of this channelised Tank Stream continue to serve as a stormwater drain beneath the northern part of the central business district.

Busby's Bore – the second water supply

The encroachment of the settlement and progressive pollution of the Tank Stream saw a greater reliance on inland sources of water, wells and captured rainwater stored in cisterns. Drought conditions during the 1810s and continued growth of the city meant that, by the 1820s, a new source of water was desperately required. By 1826 the Tank Stream had ceased all use as a potable water supply [13] and water was carted from the Lachlan Swamps in what is now Centennial Park while plans were made for a new supply.

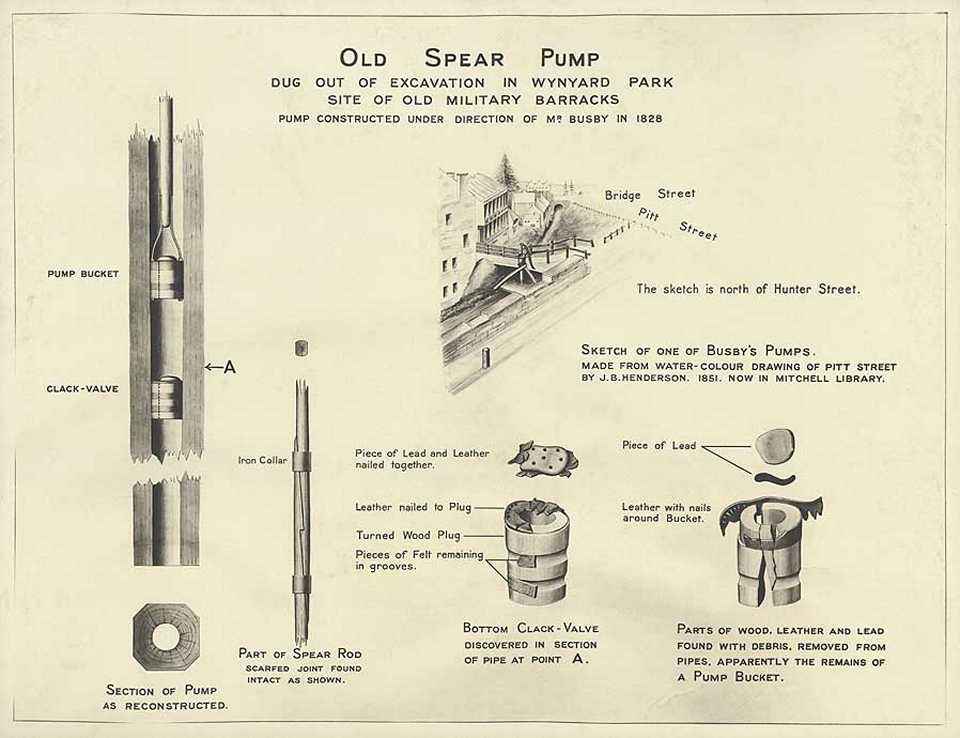

[media]Mining engineer John Busby arrived in New South Wales in 1824 and by 1827 had been given the commission to design and supervise the construction of a tunnel to bring water from [media]the Lachlan Swamps into Hyde Park. Construction of the tunnel took 10 years and was conducted by convict labour working solely with hand tools. The men drove the tunnel over a distance of about four kilometres and with a height of generally less than 1.5 metres. The tunnel was constructed using a series of shafts, 28 in total, driven down to the desired depth, with horizontal tunnels struck out between them. Ground conditions varied between rock and loose sand. The path of the bore is rather irregular, with several portions of the tunnel heading off at odd angles. This was at least in part due to the Bore following the solid rock wherever possible, [14] however there persists a story that Mr Busby refused to enter the bore with the convict labour force to supervise the work directly, preferring to provide direction from the surface. This is said to have led to several false starts in the tunnelling. [15] Scepticism that the project would ever be completed was evidenced in the newspapers at the time, [16] as well as Mr Busby bearing the brunt of many jokes about the 'great bore'. [17]

The bore began to provide limited water as early as 1830 but the full extent of the tunnel was not completed until 1837. Pumps were installed at the Lachlan Swamps in 1854 to increase the flow and in 1858 the Botany Swamps Scheme came into operation. The bore was cleared of debris and extensively surveyed in 1872, which dramatically increased its flow. It was however prone to contamination from surface runoff, and by 1902 the water had been diverted to the Royal Botanic Gardens for the purposes of flushing the ponds. In 1934 much of the bore was filled with sand to limit the risk of subsidence and collapse. [media]While the bore remains in existence, it is disused and no longer accessible.

The Botany Swamps Scheme – the third water supply

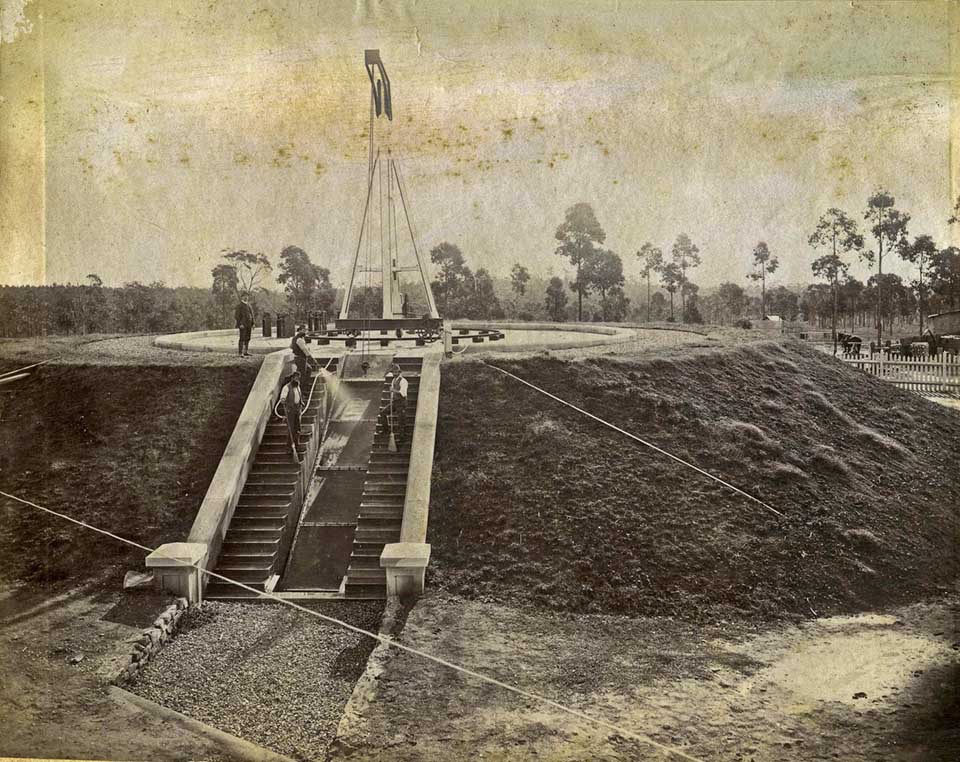

[media]The Council of the City of Sydney was established in 1842, and took control of most municipal services, including water. A prolonged drought in the 1840s saw Council appoint a special committee in 1850 to investigate the issue of improving the water supply. The report of the committee was received in 1852 and the colonial government separately appointed a Board to examine the use of the Botany Swamps specifically. The Council was replaced by the City Commissioners in 1854 and one of their early actions was to establish a steam pump in what is now Alison Road, Randwick, to pump water from the Lachlan Swamps into Busby's Bore, to augment supply. [18] Work commenced on the Botany Swamps Scheme; however much of the affected land had been the subject of earlier land grants and had to be progressively resumed.

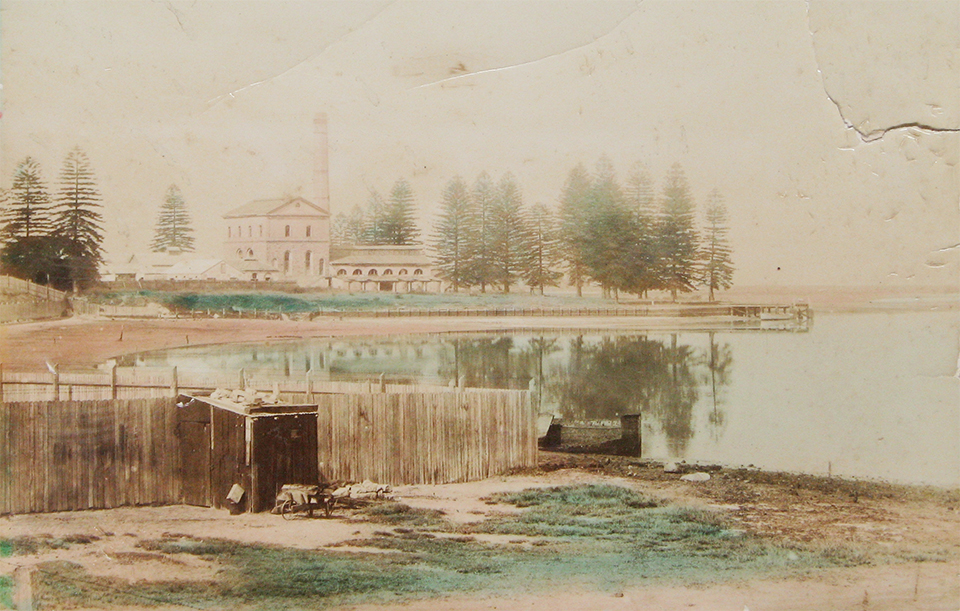

A substantial [media]steam pumping station located within what is now Sydney Airport drove the Botany Swamps Scheme. Fragments of its footings and a truncated section of the pumping station smokestack still exist and, for many years, served as a vent for the Southern and Western Suburbs Ocean Outfall Sewer. The station pumped water through 6.5 kilometres of water main into a reservoir in Crown Street, Surry Hills, which opened in 1859. Crown Street Reservoir, located at the corner of Crown and Campbell Streets, remains in service and is the oldest operating part of the water supply system in Sydney. The scheme also pumped water to the Paddington Reservoir on Oxford Street, which was completed in 1864. The Paddington Reservoir is no longer in service, but has been adapted and reused as the new Paddington Reservoir Gardens:[media] an urban park with a sunken garden and a lake of contemplation at its centre, in homage to the reservoir's past.

[media]Despite the expansion of the water supply system, the city continued to grow and the pace of growth often outstripped the ability of the water supply system to cope. Water shortages continued through the 1860s and further works were undertaken to expand the water captured at Botany Swamps. Six additional dams were constructed to supplement the Botany Scheme starting in 1867 and were not fully completed until 1873, due to difficulties in construction and several failures of the dam walls. Concerns over the adequacy of supply saw the restriction of water to customers imposed throughout the mid-1880s.

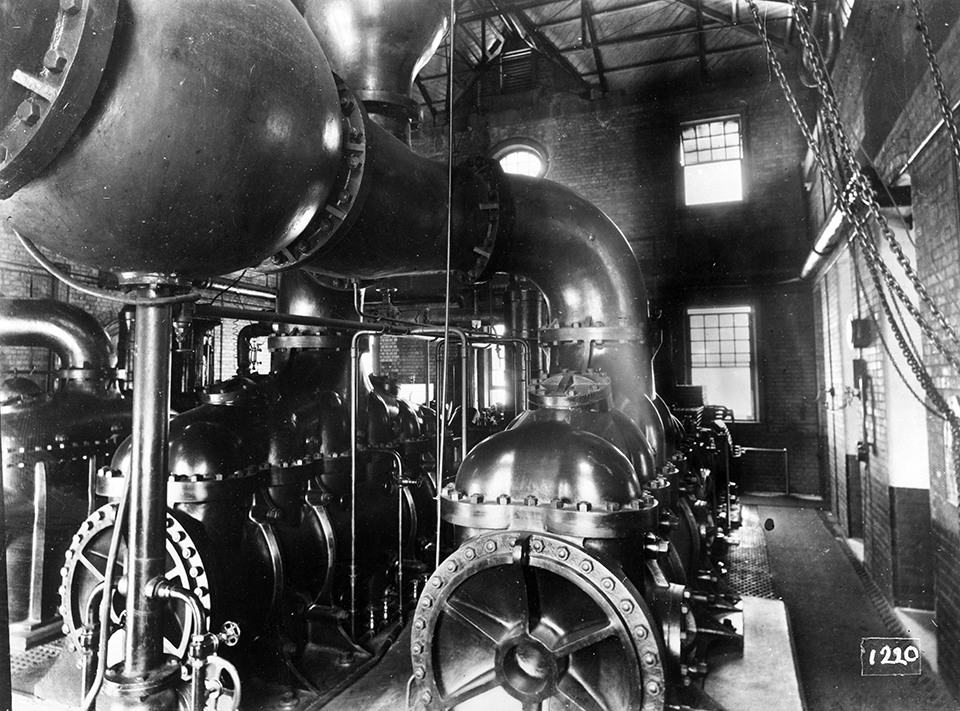

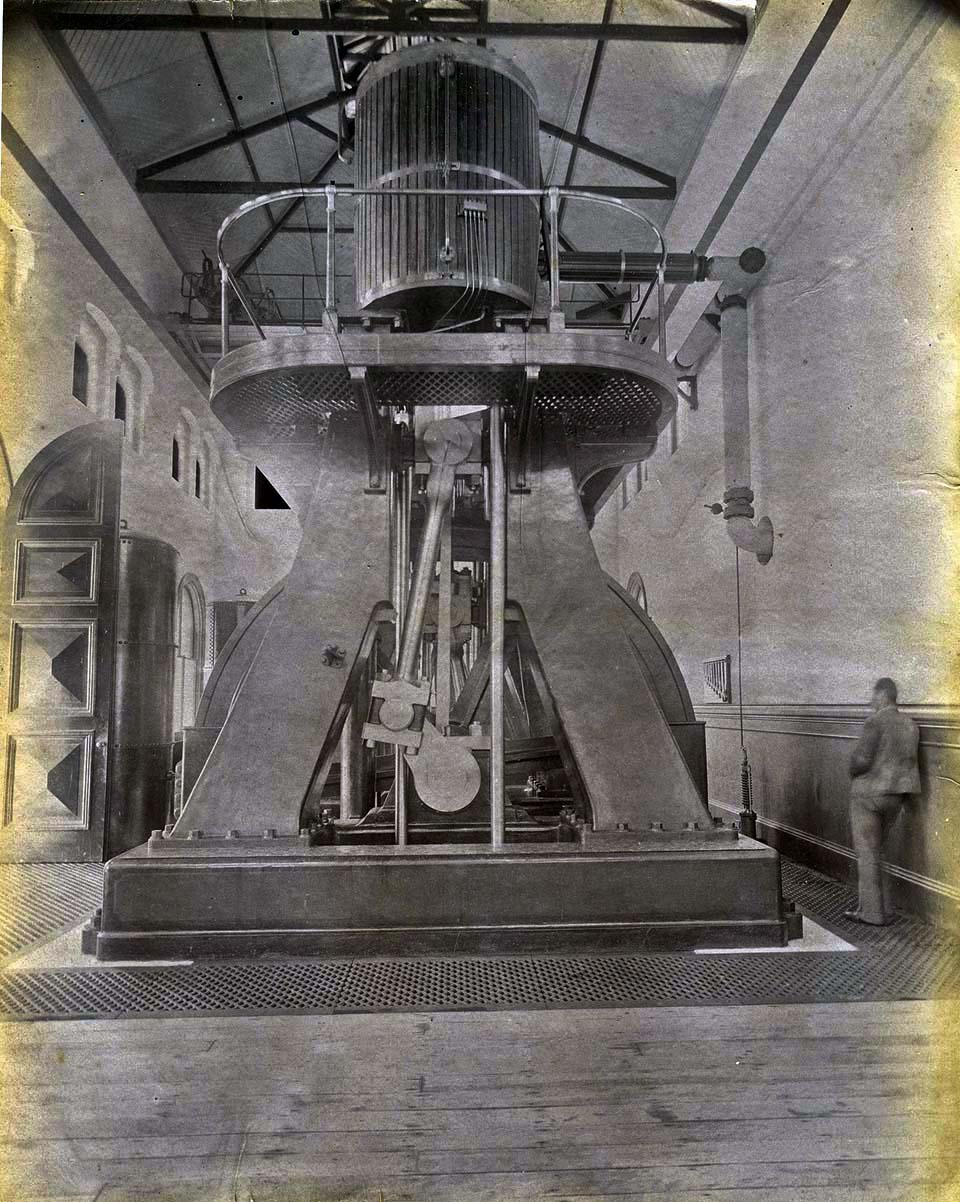

At the same time, a Royal Commission had been established to develop a long-term plan for Sydney's water supply, which ultimately recommended the ambitious Upper Nepean Scheme. Work continued to supplement the Botany Swamps Scheme, as construction of the Upper Nepean Scheme did not commence until 1880. An additional dam was built along Bunnerong Road, Botany, in 1877, and upgrades were made to [media]the pumps at Crown Street Reservoir in 1880, to help service the Woollahra area. Due to a drought, however, the Woollahra Reservoir, which had been completed in 1879, was not put into service until 1881. [19] Fears over drought in 1886 saw water delivered from the partially constructed Upper Nepean Scheme through the use of temporary flumes (open artificial water channels, utilising gravity to move water), in a system known as the Hudson Brothers' Temporary Scheme.

[media]With the Upper Nepean Scheme at least partially in operation by early 1886, the Botany Scheme was progressively wound down. 1886 was the last year the pumps at the Botany end of the scheme were fully used and, while they were kept operational until 1893 as a backup supply, by 1896 the pumps were decommissioned and sold. Many of the components of the Botany Scheme, including reservoirs and mains, were connected into the system now supplied by the Upper Nepean Scheme, and some of those components remain in service today.

The Hudson Brothers' Temporary Scheme

While the Upper Nepean Scheme was well underway by the early 1880s, there was a concern that severe drought would hit Sydney before the scheme could come fully into operation. In 1885 a proposal was received from the Hudson Brothers' engineering works at Clyde to connect the disparate and partially built sections of the Upper Nepean Scheme with a series [media]of temporary pipes and flumes, allowing water to be delivered to the Botany Swamps in advance of the full completion of the new system. About seven months after the proposal was accepted by government, the Temporary Scheme started operating on 30 January 1886. The Temporary Scheme was dismantled in 1888 after the Upper Nepean Scheme came fully into operation and no substantial remains of the Temporary Scheme exist. Some areas of the Upper Canal, such as the headwalls of the aqueduct over Simpsons Creek at Appin, show evidence of where pipework for the Temporary Scheme connected into the partially built canal; however the major components of the Temporary Scheme have been long since removed.

The Upper Nepean scheme – the fourth water supply

[media]The Upper Nepean Scheme was one of the largest engineering works undertaken in Australia in the nineteenth century. An ambitious scheme to transport water nearly 100 kilometres into the city, the Upper Nepean Scheme was built between 1880 and 1888. Over a decade of debate had occurred before the scheme commenced, in part due to the very high cost involved. In 1879 just over £1 million in public funds was borrowed by the colonial government to fund the scheme, with the final cost just over £2 million. [20]

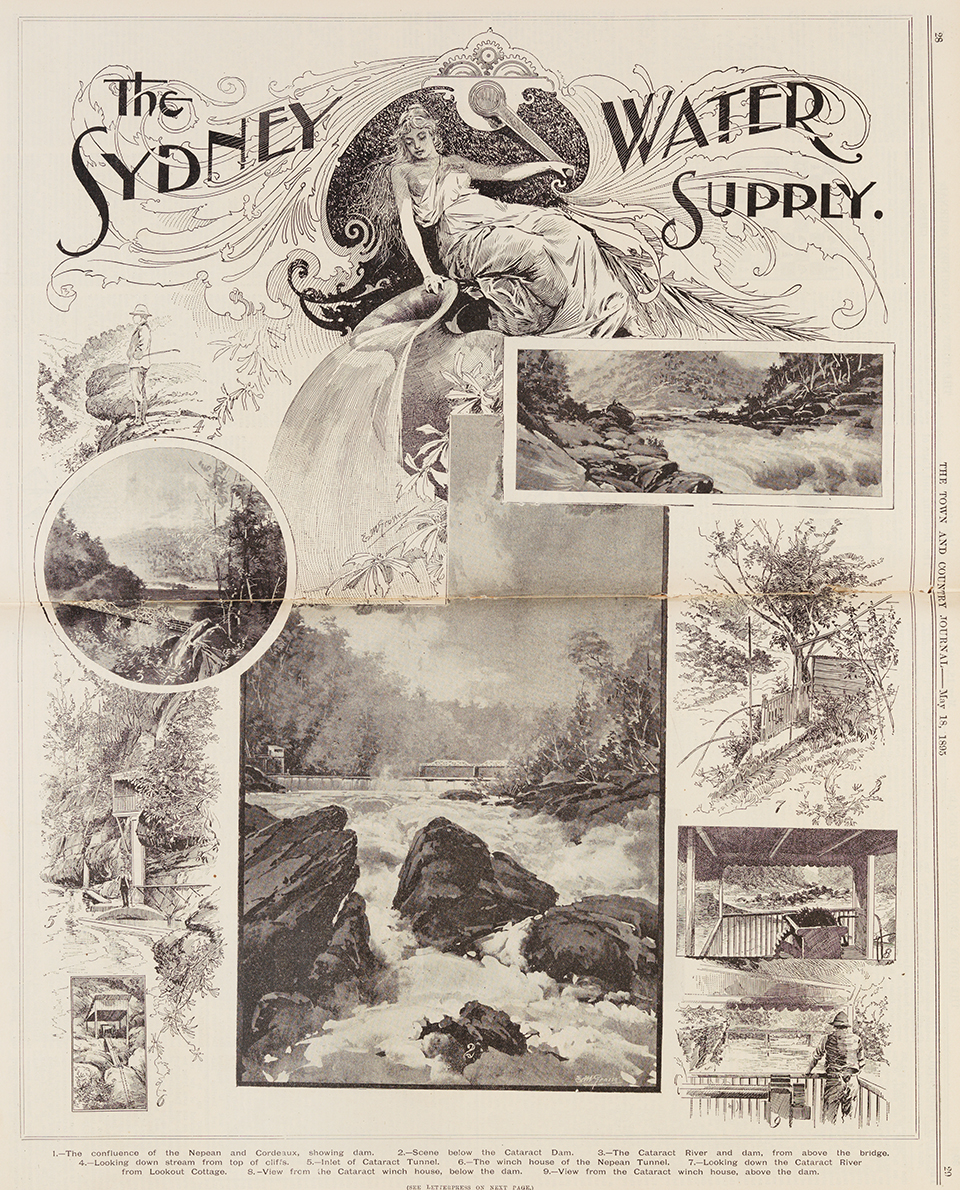

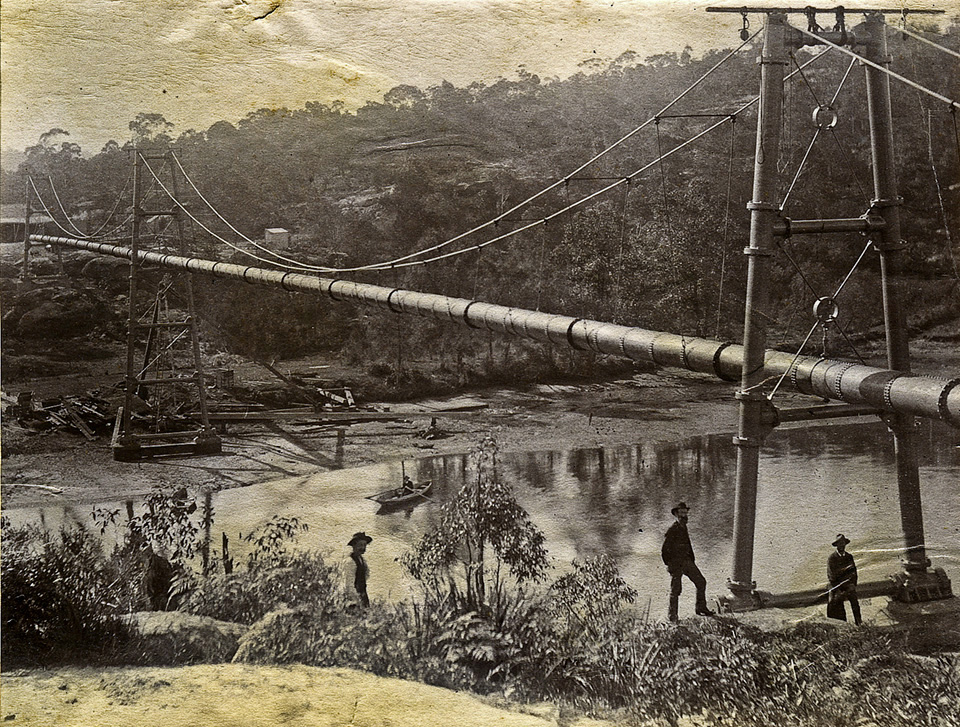

[media]The Upper Nepean Scheme, much of which is still in service, involved the diversion of water from the Nepean, Cataract and Cordeaux rivers. A weir at Pheasants Nest diverts the waters of the Nepean and Cordeaux rivers into the Nepean Tunnel, which conveys the water to the Cataract River. From there a second weir at Broughtons Pass diverts the combined waters into the Cataract Tunnel. Both tunnels were hewn out of sandstone and run for just over seven kilometres and just under three kilometres respectively. The combined water discharges into the Upper Canal at Brooks Point Road in Appin.

[media]The Upper Canal carries the water over 60 kilometres through what was, at the time, very rugged and isolated country. The Upper Canal was constructed in a mix of rock-cut open channel and sandstone blockwork in made ground; however many sections have been subsequently rebuilt in stone and concrete over the last century. Eight aqueducts convey the water across creeks and gully along the route, while 11 tunnels carry the water through hills. The entire system was designed to be fed by gravity alone and no pumping is required throughout the length of the Upper Canal.

The Upper Canal [media]originally discharged into Prospect Reservoir, a massive puddled clay dam structure in western Sydney near Blacktown, which served as the storage reservoir. A large service reservoir was constructed at Potts Hill in 1888 and a second, much larger reservoir was built adjacent to the Potts Hill No 1 Reservoir between 1913 and 1923. [21] Since 1996, the water from the Upper Canal has fed directly into the Prospect Water Treatment Plant, where it is treated and fed into pipelines to be reticulated throughout the greater Sydney area, with the Prospect Reservoir being taken off-line until 2007. Originally, however, waters received from the Upper Canal were stored in Prospect Reservoir before being fed into the Lower Prospect Canal, which carried the water through an open canal to Guildford. There the water was screened for debris at Pipehead, before entering a series of large water mains for reticulation and distribution into the city. This lower portion of the system also operated by gravitation and no pumping was required along the length of the scheme. The Lower Canal was decommissioned in 1996 due to urban encroachment, and since that time all water entering the system has been filtered. Potts Hill No 1 Reservoir has been decommissioned and Potts Hill No 2 Reservoir was upgraded and covered in 1999.

While significant portions of the Upper Nepean Scheme have been modified or (as in the case of the Lower Prospect Canal and Potts Hill No 1 Reservoir) decommissioned, the scheme remains the core of Sydney's water supply system and continues to supply up to 15 per cent of the city's total water needs.

Expansion of the water supply system

Since the completion of the Upper Nepean Scheme, Sydney's water supply needs and system have continued to expand, although this has principally been a process of adding new capacity onto the existing system, rather than the wholesale creation of a new system.

To bolster the capacity of the Upper Nepean Scheme, four major dams (referred to collectively as the 'Metropolitan Dams') were constructed between 1907 and 1935. Cataract Dam was built between 1903 and 1907; Cordeaux Dam between 1918 and 1926; Avon Dam between 1921 and 1927; and Nepean Dam between 1926 and 1935. These dams were built by the Public Works Department up until 1928, when all water supply works under the management of the Public Works Department, whether complete or only partially built, were transferred to the control of the Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board (MWS&DB). [22] Two further major dams were built, at Woronora between 1929 and 1941 and at Warragamba between 1948 and 1960. All of these dams, with some modifications, remain in service as major parts of the metropolitan water supply system. Warragamba Dam itself has twice the capacity of the remaining five dams combined and remains the largest single water storage component of Sydney's water supply system. [23]

Tallowa Dam was constructed in 1976 as joint water supply and hydroelectric dam on the Shoalhaven and Kangaroo Rivers, south of Sydney, [24] and water can be pumped from that dam into the Sydney water supply system as required. Other works have been undertaken to modify, increase and expand the capacity of the system, with some of the notable recent works including the establishment of a deep water offtake at Warragamba Dam in 2006, which increased the quantity of accessible water within the reservoir; the establishment of a Raw Water Pumping Station at Prospect Reservoir in 2007, which allowed water within the reservoir to be pumped into the Prospect Water Filtration Plant (thus bringing the reservoir back into service); and the construction of the Sydney Desalination Plant at Kurnell, which came into operation in January 2010.

Changing management of Sydney's water needs

The construction of the Upper Nepean Scheme saw a significant change in the way the city's water was managed. Prior to 1842 the supply of potable water was the responsibility of the colonial government and in 1842 became the responsibility of the City Council. [25] Expertise was largely sourced from consultant engineers brought in from overseas or provided by the Department of Public Works, which was established in 1859.

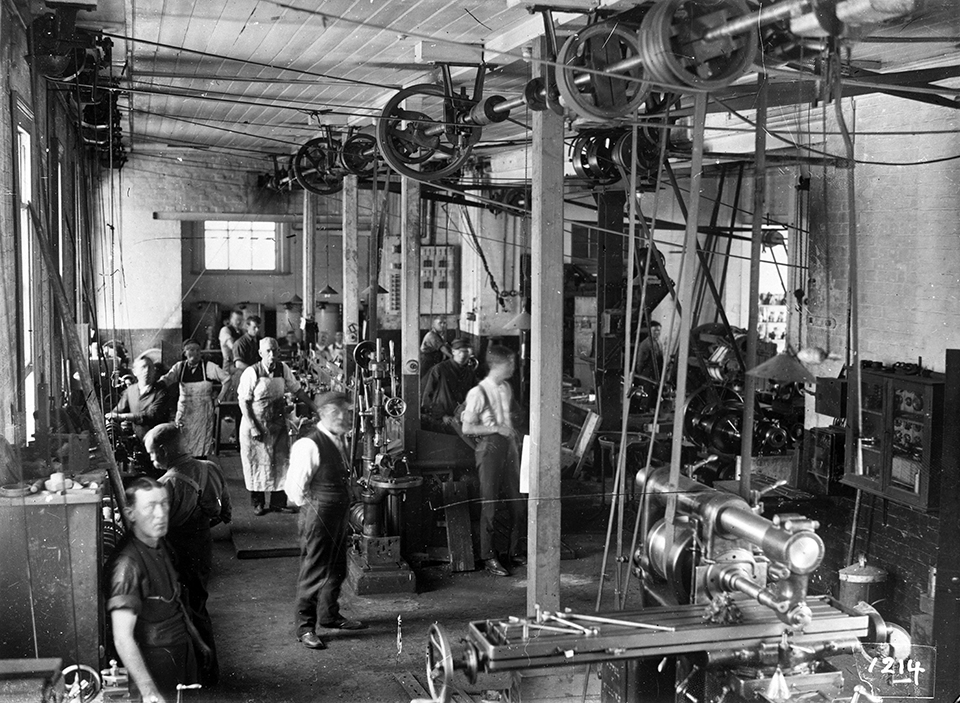

With the establishment of the Upper Nepean Scheme, the Board of Water Supply and Sewerage was created, which took control for the operation and management of the water supply and sewerage needs of Sydney. While the Act establishing the Board was passed in 1880, the Minister for Public Works held the responsibility for the construction of the Upper Nepean Scheme, and the Board did not formally come into being until 1 March 1888. [26] [media]The Board took over the water and sewerage works previously operated by the City of Sydney, as well as taking wider responsibility for these works in the County of Cumberland. In 1892 the Board's name was changed to the Metropolitan Board of Water Supply and Sewerage to differentiate it from the Hunter District Water Board. [27]

[media]In 1924 the Board's responsibilities were expanded to include stormwater drainage and it was renamed the Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board. The MWS&DB, as it was known, continued to operate until 1987 when it was reorganised as the Sydney Water Board. A further reorganisation and corporatisation took place in 1995 and, since that time, the organisation has been known as the Sydney Water Corporation. In 1999, the management of the catchment areas was transferred to a separate organisation known as the Sydney Catchment Authority.

The Board was initially based in rented premises at Circular Quay, before constructing its head office at Pitt Street in 1893. That building was extended in 1918; however both buildings were demolished in 1937 for the construction of a new building on Pitt Street. In 1965 an office tower was built on the Bathurst Street frontage of the site, with internal connections to the 1937 building. Both buildings were vacated and sold in 2009, with the relocation of the Sydney Water Corporation head office to Parramatta. Since its establishment, the Sydney Catchment Authority has been based in Penrith.

References

Margo Beasley, The Sweat of Their Brows: 100 Years of the Sydney Water Board 1888–1988, Sydney, Sydney Water Board, 1988

N Thorpe, 'Water supply and sewerage', in D Fraser (ed), Sydney: From Settlement to City: An engineering history of Sydney, Crows Nest, Engineers Australia, 1989

WV Aird, The Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage of Sydney, Sydney, Metropolitan Water, Sewerage, and Drainage Board, 1961

FJJ Henry, The Water Supply and Sewerage of Sydney, Sydney, Metropolitan Water, Sewerage, and Drainage Board, 1939

T J Roseby, Sydney's Water Supply and Sewerage: 1788 to 1918, Sydney, Government Printer, 1918

Metropolitan Board of Water Supply and Sewerage, Official Handbook 1913: Second Edition, Sydney, Bloxham & Chambers Printers, 1913

Shirley Fitzgerald, Sydney 1842-1992, Sydney, Hale & Iremonger, 1992

Notes

[1] Governor Phillip to Lord Sydney, 15 May 1788, Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 1 part 2 (Phillip) 1783–1792, pp 121–122

[2] William Bradley, A voyage to New South Wales: The journal of Lieutenant William Bradley RN of HMS Sirius, 1786–1792, facsimile reprint, Trustees of the Public Library of New South Wales, Sydney, 1969, p 62

[3] J White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (1790), pp 34–35; 77, Alec Chisholm (ed), Angus & Robertson in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, Sydney, 1962, pp 64–65, 88. See also David Hill, 1788: The brutal truth of the First Fleet, William Heinemann Australia, North Sydney, p 110

[4] Sketch of Sydney Cove, Port Jackson, in the County of Cumberland, NSW July 1788. See also William Bradley, A voyage to New South Wales: The journal of Lieutenant William Bradley RN of HMS Sirius, 1786–1792, facsimile reprint, Trustees of the Public Library of New South Wales, Sydney, 1969, View 12 ff84. Also Chart 7 – Sydney Cove as at 1 March 1788

[5] A Survey of the Settlement in New South Wales, New Holland, 1792

[6] W Tench, in Sydney's first four years: being a reprint of 'A narrative of the expedition to Botany Bay' and 'A complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson', Angus and Robertson in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, Sydney, 1961, pp 121–122

[7] William Bradley, A voyage to New South Wales: The journal of Lieutenant William Bradley RN of HMS Sirius, 1786–1792, facsimile reprint, Trustees of the Public Library of New South Wales, Sydney, 1969, p 85

[8] FJJ Henry, The Water Supply and Sewerage of Sydney, Metropolitan Water Sewerage and Drainage Board, Sydney, 1939, pp 42–43

[9] Governor John Hunter, 22 October 1795, Government and General Order, Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 2 (Grose and Patterson), 1793–1795, p 326

[10] Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 16 October 1803, p 2, online at http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article625823

[11] Government and General Order, 8 February 1810 , Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 7 (Blight & Macquarie) 1809–1811, p 285

[12] TJ Roseby, Sydney's Water Supply and Sewerage 1788 to 1918: Commemoration Volume, William Applegate Gullick, Government Printer, Sydney, 1918, p 21

[13] Margo Beasley, The Sweat of Their Brows: 100 Years of the Sydney Water Board 1888–1988, Sydney, Sydney Water Board, 1988, p 3

[14] Sydney Herald, 5 December 1836, p 2, online at http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12858794

[15] WV Aird, The Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage of Sydney, Sydney, Metropolitan Water, Sewerage, and Drainage Board, 1961, p 7

[16] Australian, 24 March 1830, p 3, online at http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article36866006

[17] Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 5 January 1832, p 2, online at http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2204331

[18] WV Aird, The Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage of Sydney, Sydney, Metropolitan Water, Sewerage, and Drainage Board, 1961, p 11

[19] WV Aird, The Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage of Sydney, Sydney, Metropolitan Water, Sewerage, and Drainage Board, 1961, p 12

[20] WV Aird, The Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage of Sydney, Sydney, Metropolitan Water, Sewerage, and Drainage Board, 1961, p 17

[21] FJJ Henry, The Water Supply and Sewerage of Sydney, Metropolitan Water Sewerage and Drainage Board, Sydney, 1939, pp 91–93

[22] WV Aird, The Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage of Sydney, Sydney, Metropolitan Water, Sewerage, and Drainage Board, 1961, pp 216–17.

[23] WV Aird, The Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage of Sydney, Sydney, Metropolitan Water, Sewerage, and Drainage Board, 1961, Appendix 3

[24] N Thorpe, 'Water supply and sewerage', in D Fraser (ed), Sydney: From Settlement to City: An engineering history of Sydney, Crows Nest, Engineers Australia, 1989, pp 17–40

[25] WV Aird, The Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage of Sydney, Sydney, Metropolitan Water, Sewerage, and Drainage Board, 1961, p 215

[26] WV Aird, The Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage of Sydney, Sydney, Metropolitan Water, Sewerage, and Drainage Board, 1961, p 216

[27] WV Aird, The Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage of Sydney, Sydney, Metropolitan Water, Sewerage, and Drainage Board, 1961, p 215