The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The foundation of the Workers' Educational Association Sydney

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

[media]The Sydney branch of the Workers’ Educational Association (WEA) is one of Australia’s oldest and most prominent provider of continuing education for adults. It began in 1913 as a joint undertaking by the trade union movement and the University of Sydney to build a progressive organisation committed to enabling adult working people to gain a liberal education. Throughout its history it has been non-partisan and non-political, despite significant pressure from both within and without, and student-directed. The WEA's democratic structure has provided it with a strong foundation to meet shifting community and government expectations of adult and continuing education and to remain relevant in the twenty-first century.

The origins of the WEA

[media]The Workers’ Educational Association began in the United Kingdom in 1903, when Albert and Frances Mansbridge decided to combine the traditions of the English cooperative education movement and university education in ‘An Association to promote the Higher Education of Working Men’. Two years later, after the name offended the Women’s Cooperative Guild, the Mansbridges renamed their organisation the Workers’ Educational Association.[1]

The English WEA was founded with the intention of helping working people gain the knowledge necessary to wield political and industrial power. By 1907 it had formalised a model of tutorial classes run by joint committees of WEA and university representatives. Participants had to commit to three-year courses and produce an essay each month and students were expected to achieve the standard of university work in honours.[2] WEA members and students guided the courses offered by the universities – a participatory approach that was revolutionary, but the organisation did not follow any system of class analysis. Indeed, its pledge that it was non-partisan and non-sectarian appealed to elites who hoped to guide the intellects of the labouring classes in reformist principles, rather than socialism.[3]

WEA enters the workingman’s paradise

In the early twentieth century, Australia and New Zealand were seen as social laboratories where democratic achievements and social reform had created a ‘workingman’s paradise’.[4] Traditions of self-help and cooperative organisation found expression in the development of numerous friendly societies and cooperatives, Schools of Arts and Mechanics’ Institutes, and trade unions. It was a period of civic experiments that were guided by progressive ideals about the role of education, health and social policy in the wellbeing of the common people, and of the nation as a whole.[5]

One of the most progressive civil servants at the time was the director of the New South Wales Department of Public Instruction, Peter Board. Best known for reshaping the entire system of public education in NSW, he also sat on the Sydney University Senate. In 1910 English WEA president Reverend William Temple visited Australia and met with Board, who travelled the following year to the UK to investigate continuation schools. When Board returned he established government-funded Evening Continuation Schools[6] and drafted legislation to enable Sydney University to offer evening tutorial classes in science, economics, ancient and modern history, and sociology.[7]

Independently Mansbridge wrote to David Stewart, a Sydney-based Scot who was a member of the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners and delegate to the Sydney Trades and Labour Council, and invited him to help establish a branch of the WEA in New South Wales. Stewart approached the Minister for Public Instruction, AC Carmichael, and HE Barff, Registrar of the University of Sydney, which resulted in a meeting with Peter Board. The University was initially unenthusiastic but the Labour Council embraced the idea, despite some resistance from members like the Secretary of the Builders’ Labourers Union who apparently asked ‘What the hell does a bricky’s labourer want with culture?'[8] and by May 1913 Professor WJ Woodhouse and Dr FA Todd were discussing extension classes in meetings at Trades Hall.[9]

The Mansbridges set sail for Australia on the HMS Orama. When their ship docked in Western Australia in July, Mrs Mansbridge told the press the WEA sought to unite learning with the experience of daily life and to educate people by bringing about ‘the union of the working people and the scholars’:

'Our association,' said Mrs. Mansbridge, 'has never attempted to deal directly with economic or political reform, but it has sought to equip its members, and any who will listen to it, with increased mental power and the spirit of comradeship, so that they might the better deal with problems of social betterment, either in their capacity as individuals or as members of industrial, political, or other bodies.'[10]

On their arrival in Sydney on 29 July 1913, Mansbridge spoke to The Daily Telegraph about his idea that adults cannot be educated in the same manner as children and said, ‘we have a saying that in a class of 30 students all are teachers’.[11]

[media]In October 1913 the University Senate agreed to establish a Joint Committee for tutorial classes. The New South Wales Branch of the WEA was officially formed at a conference of delegates from 28 affiliated organisations that was held at Trades Hall on 3 November 1913. Mansbridge presided and reported that branches were being formed in Newcastle, Wollongong and Broken Hill, Queensland, South Australia, Victoria and Tasmania. The meeting drafted a constitution that gave the NSW Department of Education and the University two representatives upon the central committee of the Association. David Stewart was appointed general secretary of the New South Wales Association,[12] a role he would serve for the rest of his life.

The WEA was on its way. Courses ran on the British three-year model, beginning with Professor Irvine’s ‘Economics and History’ course, although Truth revealed the frictions already apparent in this union of the University and the workers:

Snobbishness — An incident showing the ingrained snobbishness of lackeys is reported from the Workers' Educational Association. Professor Irvine wanted some scribbling paper. He asked Mr. Burgess, secretary of the W.E.A. (Sydney branch), to go to the office and obtain some. Applying at the office he was met by the clerk, who said: 'This is the University, and not the Trades Hall; you Trades Hall push are not going to run this show.' He wouldn't trust the secretary with the paper, so he brought it up to the class himself. Anything more snobbish than this would be hard to imagine.[13]

Surviving the Great War

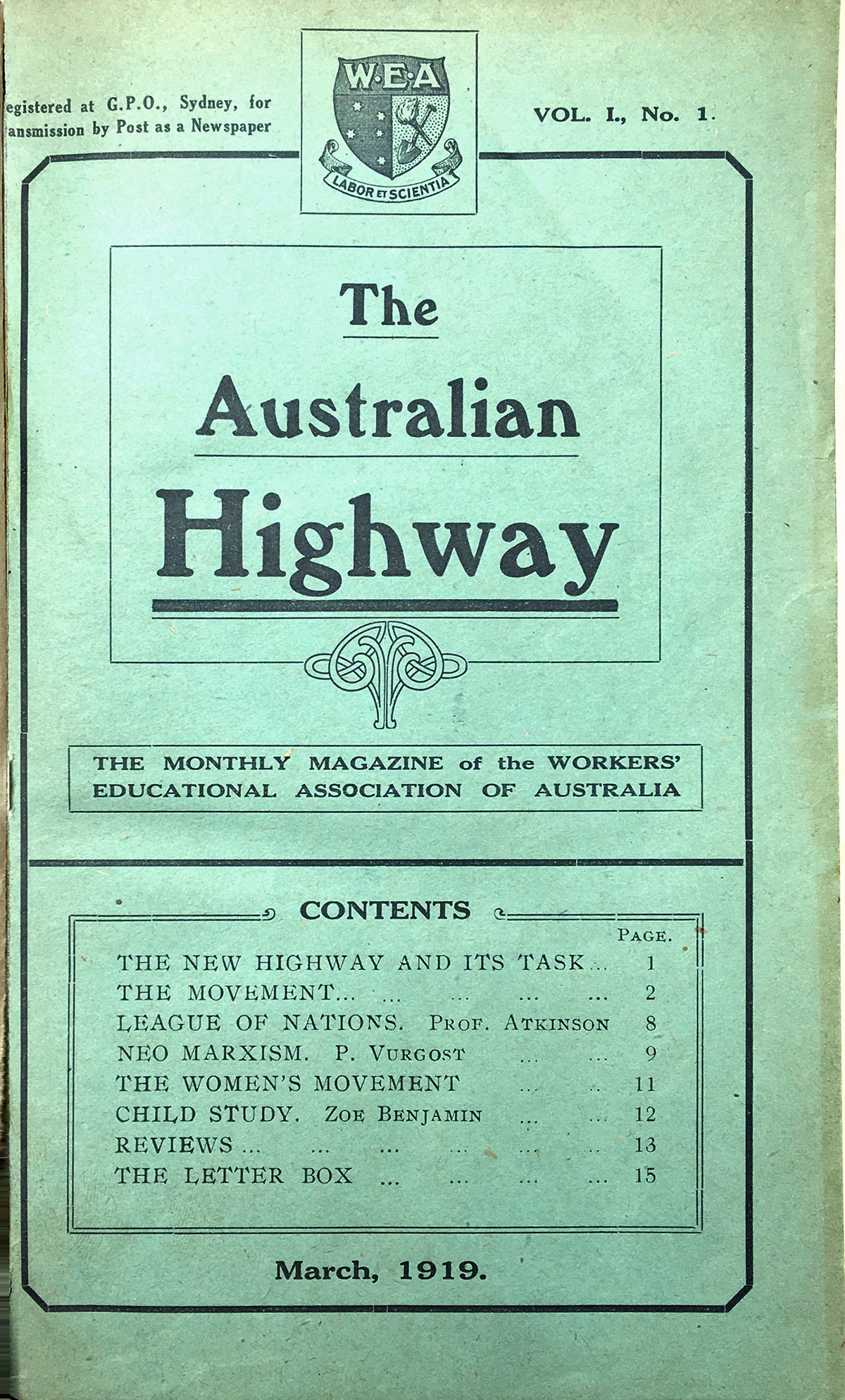

[media]By 1914, the WEA had 55 affiliated organisations, largely due to the efforts of David Stewart to win union support. By 1915 there were branches in every Australian state and New Zealand and Stewart was provisional Commonwealth secretary. The Central Council of the WEA also began a long tradition of publishing by producing a monthly NSW supplement to the British organ The Highway, as well as a Provisional Handbook.[14]

The WEA met at Trades Hall, although it was not an easy relationship. The Trades Hall Association objected to non-union students using its library and when the WEA stated this was an attack on its principles of non-partisanship, the Trades Hall Association disaffiliated from the Central Council.[15]

The first serious challenge to the WEA’s non-partisan and non-political approach came from within the organisation. In 1914 Sydney University had appointed Oxford graduate Mr Meredith Atkinson as its first director of the Department of Tutorial Classes of the University of Sydney.[16] Atkinson was recommended by Mansbridge, and from 1915 to 1918 served as president of the Australian WEA. Atkinson saw himself as a missionary for the movement in Australia and New Zealand:[17]

In Australia there seems to me to be an almost ideal environment for the accomplishment of the great aims of the WEA–the creation of an educated democracy, a nation of men and women moved to give of their best to the country.[18]

[media]Atkinson’s tenure coincided with the Great War, which was an enormous political test for workers and the labour movement. When Labor Prime Minister William Morris ‘Billy’ Hughes and Labor Premier William Holman responded to mounting losses by urging conscription, they triggered corrosive debates within the labour movement that split its political and industrial wings.[19] Atkinson was an impassioned conscriptionist and secretary of the Universal Service League in 1916, which was in conflict with the vast majority of the WEA’s affiliated associations. The WEA at first defended its president’s right to freely express his political views, but formally dissociated itself from them in December 1916. Atkinson’s advocacy also embarrassed his university colleagues, who in any case objected to his overweening personal ambition.[20] In 1917 Atkinson left for Melbourne University, where he served another five years with the WEA before running into similar troubles.[21] The WEA was severely damaged – its position within the trade union movement was permanently weakened and the university held an inquiry that resulted in a reduction in the WEA’s input into tutorial classes.[22]

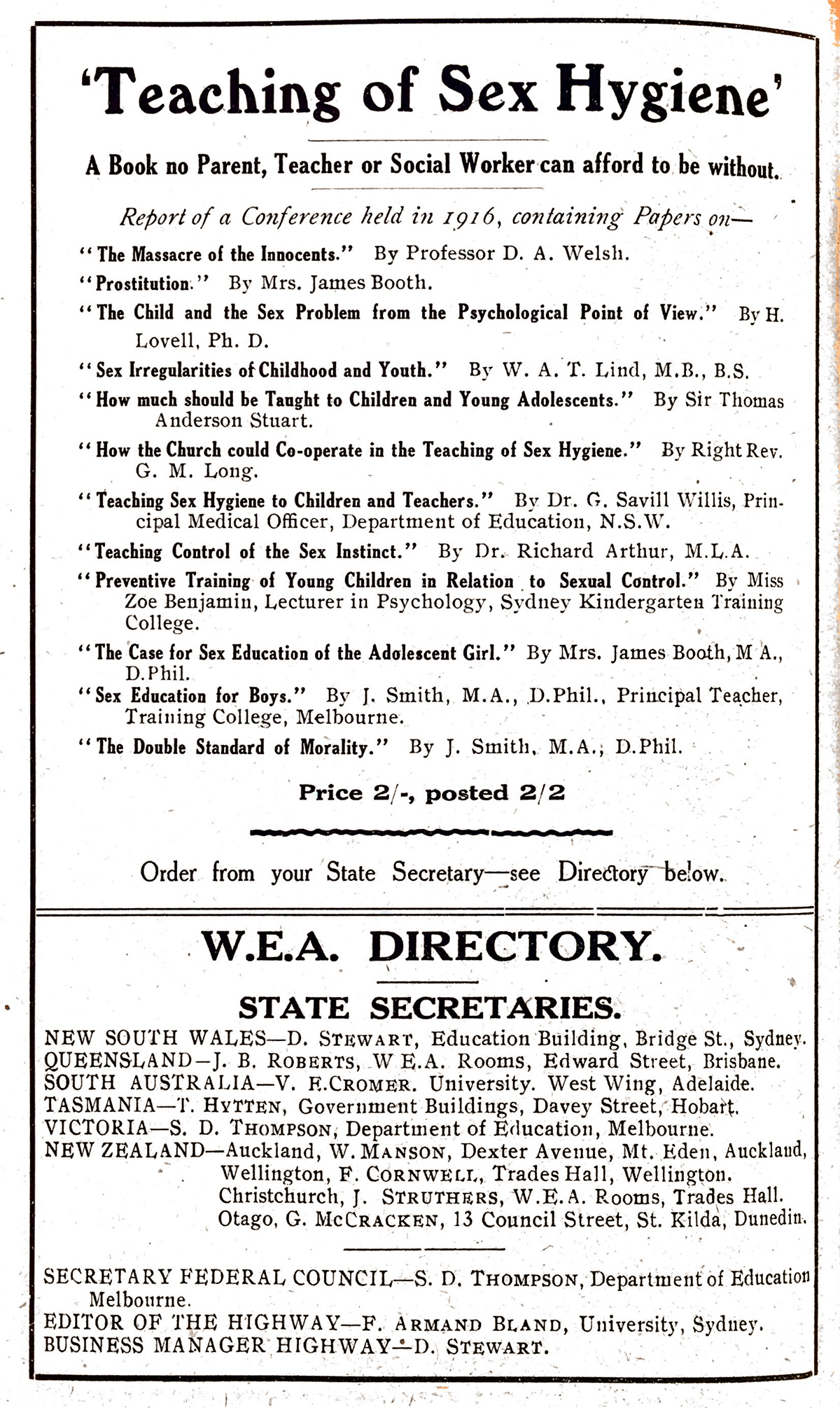

Even so, the WEA’s wartime offerings were adventurous.[23] In conferences and public lectures the WEA explored the topics of trade unionism, venereal disease, the political relationship between Great Britain and the self-governing dominions, prostitution, and the teaching of ‘sex hygiene.’[24] Classes ran in the industrial centres of Newcastle, Cessnock, Lithgow and Bathurst, Broken Hill and Molong, as well as in Sydney factories and shops. The WEA offered courses in economics, political science, industrial history, sociology, physiology, modern history (particularly relating to the causes of the war), English literature, law, psychology, child study and even musical aesthetics. It also employed part-time tutors who would not only leave their mark on the movement, but on the writing of Australian history, such as CH Currey and Harold Lark Harris.[25]

Between the wars

[media]At the end of the war the WEA had 80 affiliated organisations, of which 38 were unions. In November 1919 the WEA launched its journal, Australian Highway, and ran a class called ‘Problems of Finance’, that boasted five members of parliament.[26] By the time WEA had reached the end of its first decade, it had 120 affiliated courses and had delivered 43 three-year courses. It was the most prominent provider of adult education in Australia.[27]

Stewart received a very modest salary, via a state government grant, to be the council's secretary. He guided the organisation towards offering more flexible courses than the early three-year model and developed services like the WEA Book Service and the WEA Club lending library. Stewart tried to engage and attract working people, although the organisation had lost its early missionary zeal and it was apparent that the main demand for classes was from professional and business people.[28] The WEA was also working with the Australian Broadcasting Company to provide lectures over the radio and Stewart found himself at the centre of Australian cultural life when he was appointed to the first advisory council of the Australian Broadcasting Commission in 1932.[29] Funding issues intensified when the Depression bit in 1931. The grant from the University’s Department of Tutorial Classes was cut by a third and the WEA was forced to do more with much less. The American Carnegie Corporation included the WEA in its funding rounds and this enabled the foundation of a library and an international study tour for David Stewart, but this was not enough to stop the decline in the number of classes offered.[30] Despite these strictures, lectures were in high demand and in 1932 a lecture series on Russia’s Five-Year Plan achieved record attendances.[31]

[media]The WEA was also battling the University to regain equal representation on the Joint Committee, at the same time as Lloyd Ross, the director of tutorial classes and editor of The Australian Highway, was challenging the WEA to tighten its links with the labour movement to become an instrument of social change. David Stewart could not see how this could be done without abandoning the WEA’s non-partisan educational principles.[32]

World War II

The outbreak of another war led to a further drop in enrolments and more restrictions on university funding, but the WEA received support from the Australian Broadcasting Commission and a significant increase in funding from the new Labor Premier WJ McKell, along with the creation of an Advisory Committee for Adult Education.[33]

The tension within the WEA between the desire to serve liberal principles and its ties to the labour movement was inflamed once more from 1942 to 1944. The New South Wales Labor Party, the Labor Council, and the Teachers’ Federation all objected to anti-Soviet material in a political theory course known as B40. Russia was an ally of Britain’s during World War II, and was admired by most Australian left wing organisations. The Labor Council, the Teachers’ Federation and a dozen other organisations disaffiliated from the WEA and the Communist Party later boycotted the organisation, causing long term damage.[34]

[media]In other ways, the war boosted the WEA, as it provided services education and assisted the Army Education Service.[35] Adult education was an integral part of post-war reconstruction and more than 1000 people attended a 1944 WEA Sydney conference on ‘The Future of Adult Education in Australia’. However, as more providers stepped into the field, adult education became more diffuse.

The end of the Stewart era

David Stewart, the tenacious and uncompromising driver of WEA policy since 1913, died at home in Haberfield in August 1954 at the age of 71, having put in a full day of work at the WEA. He left behind an organisation serving more than 8,000 students which offered 103 courses, 31 study circles across the state, hundreds of lectures, and a summer school complex at Newport. It dominated the field of adult education and remained committed to its original, difficult mission of balancing its philosophical commitment to the workers with its desire to offer liberal education through the resources of a university.[36] The postwar era would bring new challenges.

References

Darryl Dymock,‘A special and distinctive role in adult education’: WEA Sydney 1953–2000, Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001

EM Higgins, David Stewart and the WEA, Sydney: The Workers Educational Association of New South Wales, 1957

Naomi Parry, Brad Manera, Will Davies, Stephen Garton, New South Wales and the Great War,Haberfield: Longueville Media, 2016

Jill Roe (ed), Social policy in Australia: some perspectives 1901-1975,Stanmore: Cassell, 1976

Michael Roe, Nine Australian Progressives: Vitalism in bourgeois social thought 1890–1960, St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1984

Sydney Labour History Group. What rough beast: the state and social order in Australian history,Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1982

WEA Sydney, Workers’ Educational Association, Sydney celebrates 100 years of lifelong learning, Sydney: WEA Sydney, 2013

Notes

[1] D Dymock, ‘A special and distinctive role in adult education’: WEA Sydney 1953–2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), pp 2–3

[2] D Dymock, ‘A special and distinctive role in adult education’: WEA Sydney 1953–2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), pp 3–5

[3] D Dymock, ‘A special and distinctive role in adult education’: WEA Sydney 1953–2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), pp 3–5

[4] Naomi Parry, Brad Manera, Will Davies, Stephen Garton, New South Wales and the Great War (Haberfield: Longueville Media, 2016), pp 8–9; Sydney Labour History Group, What rough beast: the state and social order in Australian history (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1982); Jill Roe (ed). Social policy in Australia: some perspectives 1901–1975. (Stanmore: Cassell, 1976)

[5] Michael Roe, Nine Australian progressives: vitalism in bourgeois social thought, 1890–1960. (St. Lucia, Qld, University of Queensland Press, 1984)

[6] Harold Wyndham, 'Board, Peter (1858–1945)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/board-peter-5275/text8893, published first in hardcopy 1979, viewed 9 April 2018

[7] D Dymock, ‘A special and distinctive role in adult education’: WEA Sydney 1953–2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), pp 4–6

[8] David Stewart, ‘Pioneering the WEA in Australasia’, The Australian Highway, Vol XXXIX (Sydney, 1947), p 20

[9] ‘Workers Educational Association’, Clarence and Richmond Examiner, Saturday 3 May 1913, page 11, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article62062159, viewed 31 March 2018

[10] 'Worker and Scholar', The Daily Telegraph, 9 July 1913, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article238978705, viewed 5 Apr 2018,

[11] 'Spreading education.' The Daily Telegraph, 30 July 1913, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article238979041, viewed 13 Aug 2018

[12] 'Workers' Educational Association.' Barrier Miner, 4 November 1913, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article45234871, viewed 5 April 2018

[13] Truth, 2 November 1913, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/rendition/nla.news-article168753581, viewed 5 April 2018

[14] EM Higgins, David Stewart and the WEA (Sydney: The Workers Educational Association of New South Wales, 1957), p 27

[15] EM Higgins, David Stewart and the WEA (Sydney: The Workers Educational Association of New South Wales, 1957), pp 24–25

[16] Warren Osmond, 'Atkinson, Meredith (1883–1929)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/atkinson-meredith-5081/text8477, published first in hardcopy 1979, viewed 9 April 2018

[17] Warren Osmond, 'Atkinson, Meredith (1883–1929)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/atkinson-meredith-5081/text8477, published first in hardcopy 1979, viewed 9 April 2018

[18] M Atkinson, ‘First impressions’, The Highway Australian Supplement, May 1914, pp 1–2, cited D Dymock, ‘A special and distinctive role in adult education’: WEA Sydney 1953–2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), p 1

[19] Naomi Parry, Brad Manera, Will Davies, Stephen Garton, New South Wales and the Great War (Haberfield: Longueville Media, 2016), pp 102–109

[20] EM Higgins, David Stewart and the WEA (Sydney: The Workers Educational Association of New South Wales, 1957), pp 36–40

[21] Warren Osmond, 'Atkinson, Meredith (1883–1929)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/atkinson-meredith-5081/text8477, published first in hardcopy 1979, accessed online 9 April 2018

[22] EM Higgins, David Stewart and the WEA (Sydney: The Workers Educational Association of New South Wales, 1957), p 38

[23] EM Higgins, David Stewart and the WEA (Sydney: The Workers Educational Association of New South Wales, 1957), p 29

[24] EM Higgins, David Stewart and the WEA (Sydney: The Workers Educational Association of New South Wales, 1957), pp 31–32

[25]EM Higgins, David Stewart and the WEA (Sydney: The Workers Educational Association of New South Wales, 1957), pp 30–31

[26] WEA Sydney, WEA 100 years: Workers’ Educational Association Sydney celebrates 100 years of lifelong learning (Sydney: WEA Sydney, 2013)

[27] D Dymock, ‘A special and distinctive role in adult education’: WEA Sydney 1953–2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), pp 12–13

[28] EM Higgins, David Stewart and the WEA (Sydney: The Workers Educational Association of New South Wales, 1957), p 43

[29] EM Higgins, David Stewart and the WEA (Sydney: The Workers Educational Association of New South Wales, 1957), pp 68–69

[30] 'Library For W.E.A. Students', Barrier Miner, 17 March 1927, viewed 17 Aug 2018 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article46002129; 'The Carnegie Grants.' The Sydney Morning Herald, 11 August 1938, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17476986, viewed 17 Aug 2018,

[31] EM Higgins, David Stewart and the WEA (Sydney: The Workers Educational Association of New South Wales, 1957), pp 59–60

[32] EM Higgins, David Stewart and the WEA (Sydney: The Workers Educational Association of New South Wales, 1957), pp 60–64

[33] EM Higgins, David Stewart and the WEA (Sydney: The Workers Educational Association of New South Wales, 1957), pp 73–76

[34] EM Higgins, David Stewart and the WEA (Sydney: The Workers Educational Association of New South Wales, 1957), pp 82–83; D Dymock, ‘A special and distinctive role in adult education’: WEA Sydney 1953–2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), pp 17–19

[35] EM Higgins, David Stewart and the WEA (Sydney: The Workers Educational Association of New South Wales, 1957), pp 73–76

[36] D Dymock, ‘A special and distinctive role in adult education’: WEA Sydney 1953–2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), pp 23–24