The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The first Government House: building on Phillip’s ‘good foundation’

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The first Government House

[media]The first Government House was not a simple singular structure but a complex with a yard, outbuildings, guardhouse, garden and greater domain. It was a home, an office and a venue for public and private entertaining, but also a symbol of British authority, with all that that meant to different people, both then and now.

A place of intimacy and officialdom, birth and death, celebration, confrontation and reconciliation, the first Government House was the scene of significant moments in the young colony's history including the 'Rum Rebellion' and, more decorously, the first meeting of the Legislative Council.

What do we mean by the 'first' Government House?

[media]The 'Governor's Mansion' features in a somewhat naive map of the infant settlement drawn in April 1788.[1] Instead of being a little-known image of the house that stood on the site on the corner of Bridge and Phillip Streets, Sydney – the first permanent viceregal residence – it is a rather ironic depiction of Governor Phillip's first home on land, the 'Govrs Temporary House' (shown at P on the map, with the 'Governor's Kitchen' at Q).

Phillip's ‘tent’

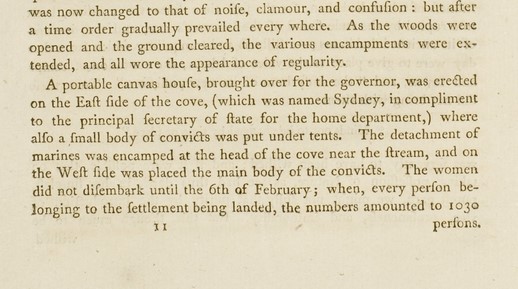

[media]When Phillip moved on shore in February 1788, he took up residence in a portable canvas house erected on the eastern side of what was to become known as the Tank Stream. A prefabricated dwelling of timber-framed panels covered with oilcloth, it cost £130 – a third of the amount paid for all the marquees and camp equipment for the marine officers. Forty-five feet long, 17 feet 6 inches wide and 8 feet high (13.7 x 5.3 x 2.4 metres high) it had a wooden floor, five windows each side, 3 foot 9 by 3 foot (.9 x 2.7 x .9 metres) and was divided internally. Often referred to as a tent, although it proved 'neither wind nor water proof', it was actually rather impressive.

This dwelling is important, not simply as Phillip's first residence in the colony, where he remained for over a year, but because of what happened there: Arabanoo was brought here; despatches were written; decisions, great and small, on the management and future of the settlement and its inhabitants were made here; the County of Cumberland was defined and named here; and royal birthdays were celebrated with many a 'huzza'.

Phillip soon outlined the shape of the fledgling settlement. By March it had been determined that

The government-house was to be constructed on the summit of a hill commanding a capital view of Long Cove [now Darling Harbour], and other parts of the harbour; but this was to be a work of after-consideration; for the present, as the ground was not cleared, it was sufficient to point out the situation and define the limits of the future buildings.[2]

The 'temporary' house

On 15 May 1788 the foundation stone was laid for what was intended as an interim structure until a more substantial residence could be built to the west. Less than two months later, Phillip forwarded his intended plan for the town to Lord Sydney. 'A small House building for the Governour [sic]', was shown overlooking the encampment on the east side of the Tank Stream. To the south-west across the valley, an area high on the ridge was set aside as 'Ground intended for the Governour's [sic] House, Main Guard, & Criminal Court'.[3]

What was to be the principal street, 200 feet wide, ran from this large block down to the waterfront

[media]In the meantime, the 'temporary' house was built into the sandstone bedrock on an elevated sloping site to the east side of Sydney Cove. Although Phillip referred to it as 'a small cottage', where he would 'remain for the present with part of the convicts and an officer's guard',[4] it was still deliberately situated in a commanding position overlooking the nascent settlement, visible to all.

On such a solid base, what was originally intended to be a single storey structure in fact became the first two-storey house in the colony. As Phillip wrote in February 1790:

The house intended for myself was to consist of only three rooms; but, having a good foundation, has been enlarged, contains six rooms, and is so well built that I presume it will stand for a great number of years.[5]

[media]The house was constructed of rendered, locally made bricks, imported crown glass and pipeclay mortar, with a shingled roof. Lime was made from oyster shells collected in the neighbouring coves. The availability – or lack thereof – of suitable building materials placed limitations on works. Until an adequate supply of lime could be located,

…the public buildings must go on very slowly…In the mean time the materials can only be laid in clay, which makes it necessary to give great thickness to the walls, and even then they are not so firm as might be wished.[6]

[media]However, at least 'Good clay for bricks is found near Sydney Cove, and very good bricks have been made'.

Beyond an overarched door with sidelights and semicircular fanlight, the central entrance hall – approximately 9 feet (2.7 metres) wide – was flanked by a room on either side, each approximately 20 by 16 and a half feet (6.1 by 5 metres) with a fireplace on the rear wall. The ceiling height on the ground floor was 9 feet (2.7 metres). Just one room deep, the house was supplemented by skillion-roofed additions at the rear bisected by a projecting gabled stairhall.

[media]The garden and outbuildings were enclosed with a timber palisade fence. A dwarf stone wall ran parallel with the front of the house with peaked-roof sentry boxes constructed at each end. The sentry boxes were soon relocated to either side of the house and the forecourt was formed into a military style redoubt with the addition of side walls and two carriage-mounted guns inside the front wall. A raised and paved entry podium led up to the front door.

[media]Two small cellars were constructed beneath the entrance hall and western room of the house where the ground fell away slightly, allowing the insertion of narrow cellar lights in the northern plinth. The compound contained a collection of outbuildings to the south and west of the main house. When the footings of the service wing were excavated in the 1980s, they indicated that it had been a far more substantial structure than previously thought and built to last. Containing the kitchen, scullery and servants' quarters, it was linked to the main house by a covered way.

A lightning conductor was placed on the centre of the roof. The violence of the thunder and lightning was much commented upon by First Fleet officers, who noted the damage done to trees, the destruction of livestock, serious injury to a sentry, and in 1793, the death of two convicts.

Phillip seems to have had his portable house relocated to the new site. It is visible in early images, a gabled panelised structure to the west of the kitchen block. Other features of the complex included the privy, located far from the kitchen and living areas and a well, which was said to have never run dry even in times of drought. The privy may have had a tiled roof. Lightly burnt clay tiles, known as pantiles, were made at the Brickfields to the south of the settlement but proved to be unsatisfactory, decaying rapidly and absorbing water. Archaeologists found many tile fragments during the excavations.

Inside the house

Little is known of the interior of the house during Phillip's term apart from stray references to items such as a chest or side-table. Presumably, locally made items supplemented campaign furniture. It seems likely that the bell hung over the door and the pictures – including the 'very large handsome print of her royal highness the Dutchess of Cumberland'[7] – which had adorned the portable house were transferred to the new abode.

[media]There is far more information about the furnishings of later governors – from inventories and orders, auction lists and descriptions of events in newspaper reports and by visitors and residents. Furniture and furnishings were imported or acquired locally but governors also brought out their own possessions, often selling them on departure. Only one view of the interior is known to exist – a cartoon mocking Governor Bligh's supposed attempt to conceal himself from arrest in 1808. It shows the bare floorboards of 'a dirty little room'[8] inhabited by a servant upstairs in the rear skillion, furnished with a simple low bed.[9]

Although effectively an English vernacular cottage or provincial farmhouse, attempts were made to distinguish it architecturally, giving it the characteristics of a more polite house better suited to its status as Government House. Applied pilasters defining the central bay created an implied breakfront with a blind roundel set in the rudimentary pediment.

The designer of the house is unknown. It has been attributed to Phillip himself, and/or Provost Marshal Henry Brewer. What is certain is that it could not have been constructed without the practical knowledge and superintendence of convict James Bloodworth, a master bricklayer who also taught other convicts how to make the bricks required in the new colony.

Phillip's abode

The house was completed in a little over a year and occupied by June 1789 in time for the traditional celebration of the King's birthday. With other priorities, and a serviceable structure as his new abode, Phillip remained in this house for the rest of his time in New South Wales and administered the colony, wrestling with the daily problems thrown up by the developing settlement and planning for its future.

Home to the governor and a handful of servants, officers and visiting mariners were entertained here, the expanded facilities providing greater avenues for hospitality. In October 1791, on the anniversary of the King's accession to the throne, 'the public dinner given at the government-house was served to upwards of fifty officers, a greater number than the colony had ever before seen assembled together'.[10]

It was on this site that Bennelong and Colbee were incarcerated in November 1789. Although Colbee fled just two and a half weeks later, Bennelong did not escape for some five months. However, in time, the first Government House complex played host to Aboriginal visitors, including Bennelong, who lived there periodically. The wider governor's domain also became the burial place for several Aboriginal people.

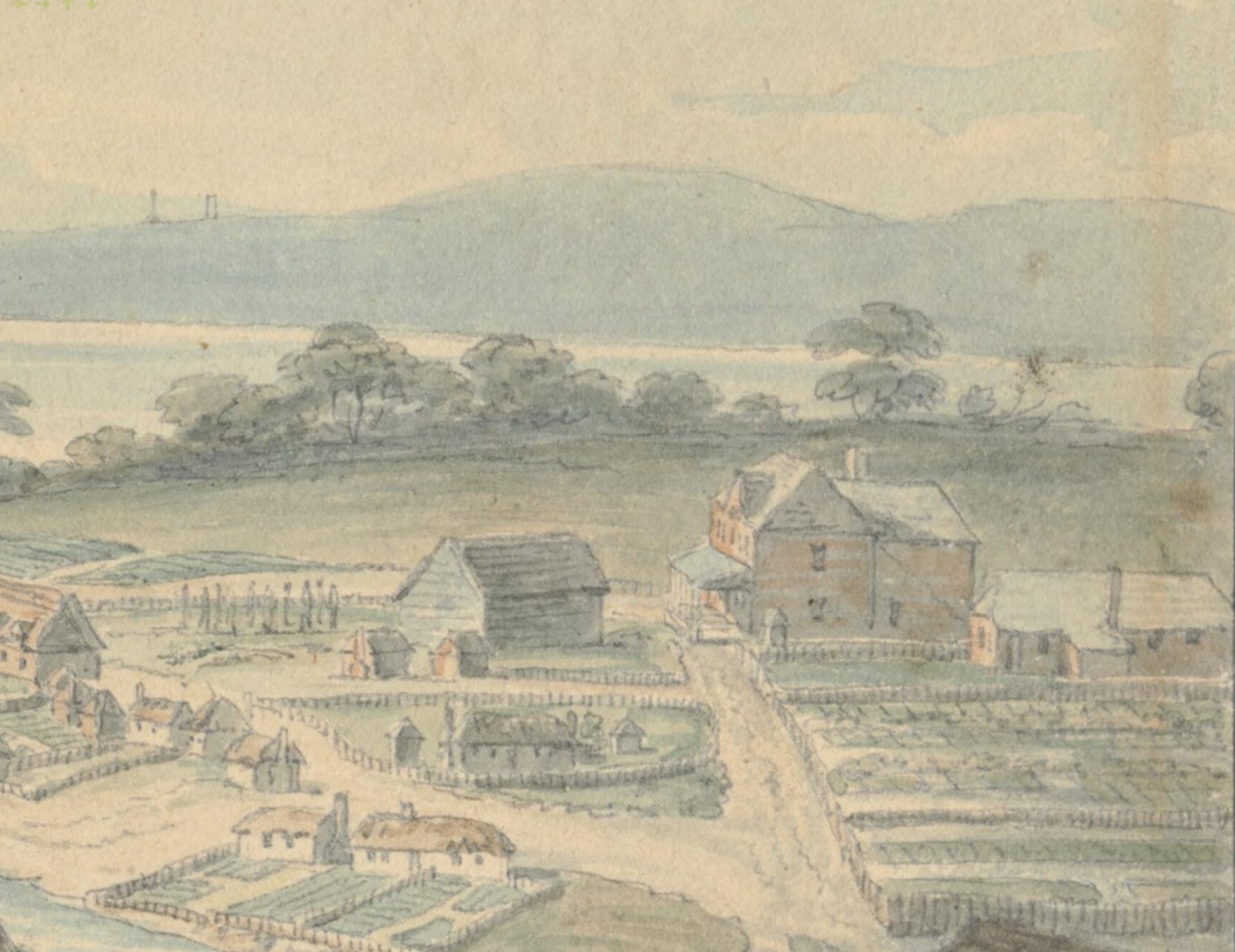

The garden in front of the house sloped down to the water's edge. Initially it was laid out in a grid, a practical design for food cultivation, with plants from England, Rio de Janeiro and the Cape of Good Hope. These were later supplemented with the first Norfolk Island pine, planted by Phillip himself, remnant native vegetation and a range of exotic species.

[media]Orange and fig trees, grape vines and vegetables all flourished. The size and flavour of the garden's produce was much remarked upon by those privileged to receive it or dine at the house on fare prepared by Phillip's French cook, whom Bennelong took such delight in mimicking. In fact, the garden became an enviable success; in May 1790 an armed watchman was stationed there each night. As David Collins wrote:

The governor's garden had been the object of frequent depredation; scarcely a night passed that it was not robbed, notwithstanding that many received vegetables from it by his excellency's order.[11]

In one of his final acts as governor, while defining the town boundaries and Crown lands, Phillip delineated the land that preserved this garden and its wider grounds as the governor's domain.

[media]When Phillip sailed for England in December 1792 his 'small cottage' was the most substantial and grandest house in the settlement. Arabanoo, taken to visit while it under construction, 'cast up his eyes, and seeing some people leaning out of a window on the first story [sic]…exclaimed aloud, and testified the most extravagant surprise'.[12] The fact that it was still the only two-storey structure in the settlement remained a novelty.

Repairs, alterations and additions

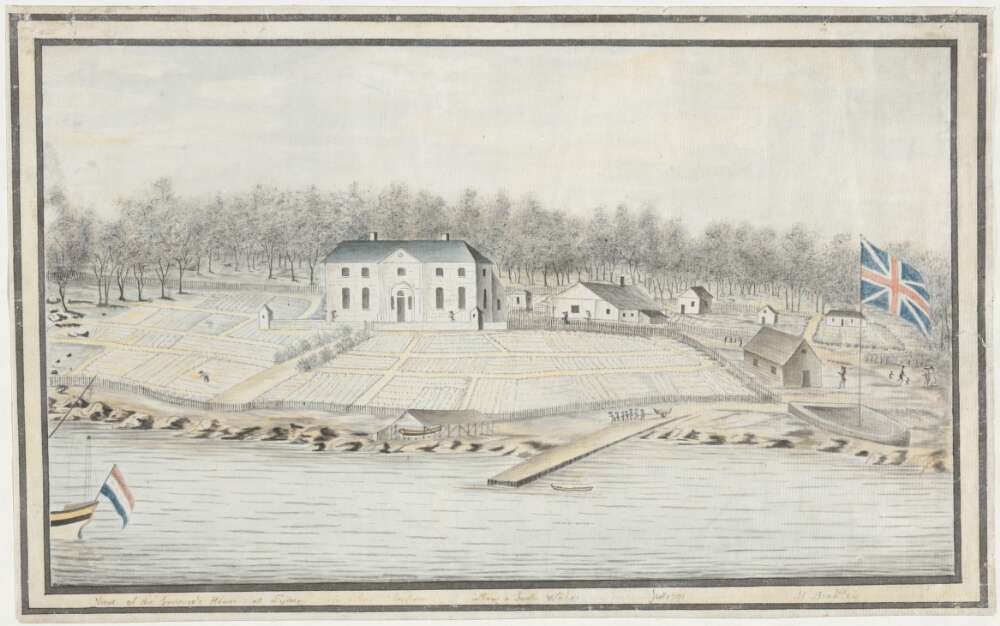

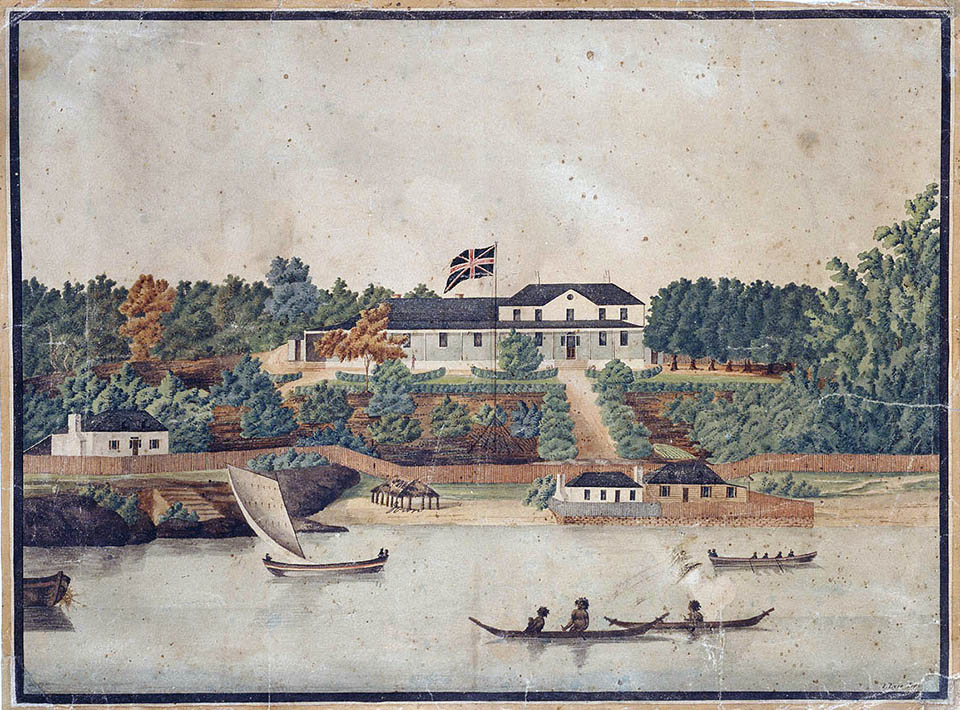

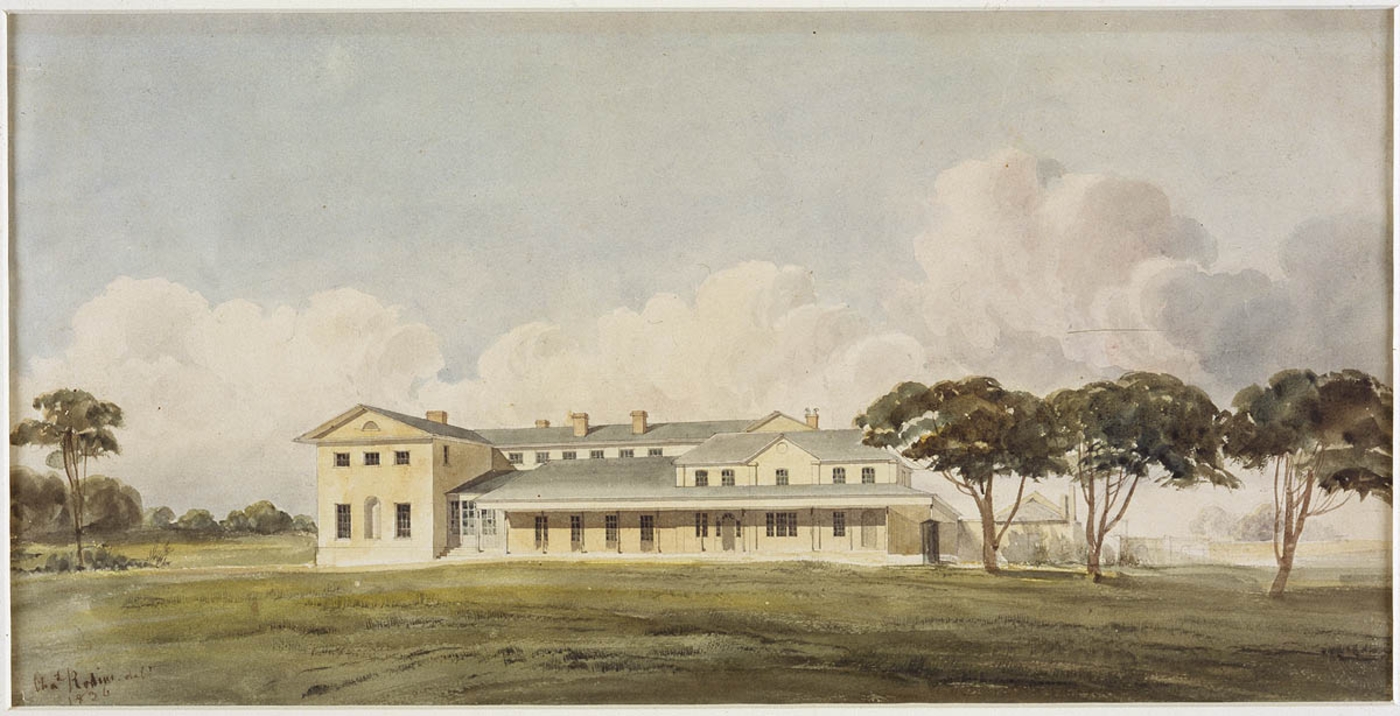

[media]Phillip's grand town planning vision had come to nought. Instead, his 'temporary' house became the heart of the home and office of the first nine governors of New South Wales. Successive governors repaired, altered and extended the house, even as they complained bitterly of its condition and unsuitability, and made plans for other accommodation.

Governor King added a long drawing room, probably with a bedroom and dressing room behind, and in the second half of 1802, extended the verandah, originally erected in about 1794. Like the [media]house itself, the garden was also becoming less utilitarian and more ornamental in character. Governor Bligh made major changes to the grounds, laying out the shrubbery in walks and removing all the rocks in the garden.

Governor Macquarie augmented the house in two stages. In 1810–12 the rear skillion rooms and stairhall were demolished and replaced and three rooms were constructed at the rear of the house: a large bow-fronted dining room, family bedroom and office. This new east wing was enlarged and given a gabled second storey in 1818–19, attributed to architect Francis Greenway. Although Governor Brisbane mainly resided at Parramatta, during his term the verandah was significantly altered or extended.

[media]In preparation for Governor Darling's arrival in 1825, new rooms were built within the roof. A servants' hall was added to the rear in 1827 with bedrooms above and two additional bedrooms were created upstairs to complete the west (or right) wing of the house to correspond generally with the left. A staircase and gallery were constructed along the front of the building by altering the roof, linking the two ends of the house. The drawing room windows were extended down to the floor or converted to French windows.

[media]The only subsequent documented changes occurred to the outbuildings. By the time Governor Darling departed in 1831 the house had reached its final known form – a rambling edifice described as 'an incongruous mass of Buildings built at different periods'[13]– but Phillip's house remained at its core.

'a perfect Hovel'

[media]By this time the first Government House was no longer the dominant house in the colony – architecturally or physically. It was inadequate both in accommodation and prestige. A 'collection of Rooms built at different times by Successive Governors' it was 'extremely inconvenient and unsightly'[14] and 'a perfect Hovel',[15] constantly damp and 'Subject to bad smells'.[16] As Governor Macquarie had assured Earl Bathurst in 1817: 'no private Gentleman in this Colony is worse off for private Accommodation for himself and Family and Servants than the Governor'.[17]

Despite the litany of complaints, and although several plans for a new Government House were prepared and authorisation for its construction was given in 1825, work was delayed due to other pressing demands. Indeed, work on the foundations of the new house did not commence until 1837. The British Government granted approval for the proposed expenditure because of:

…the growing importance of the Colony…and the necessity of maintaining in so remote a dependency of the Empire some of the visible state and splendor [sic] which should belong to Her Majesty's Representative ...[18]

There was little public concern for the impending demise of the old 'temporary' house.

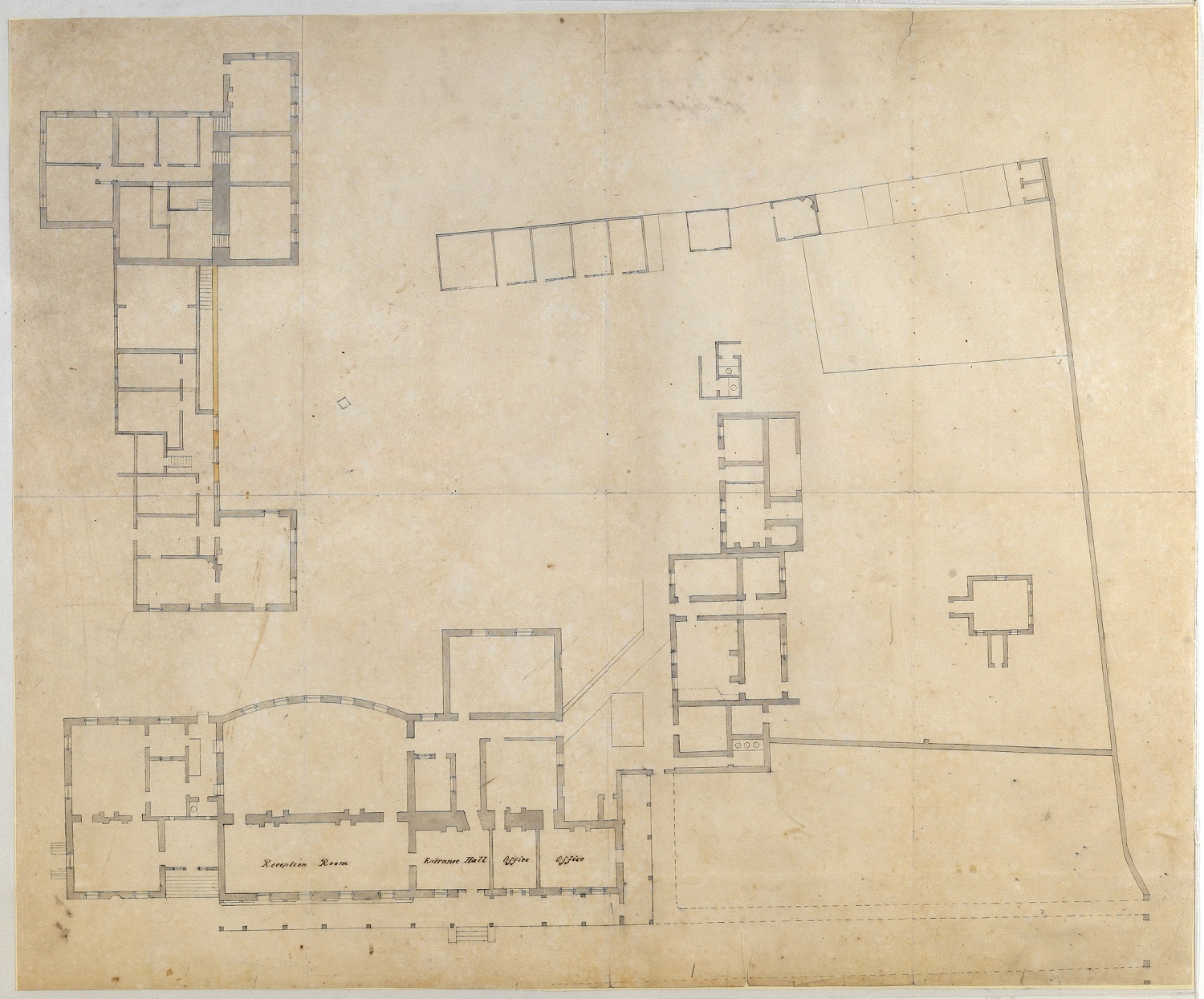

Only two plans of the first Government House are known to survive. A partial plan prepared for Governor Bligh to accompany a request for furnishings in 1807 reveals the building's simple form with Phillip's house augmented to the east by the drawing room added by Governor King.[19] This plan provides the sizes of the front ground floor rooms from which other dimensions can be calculated. In this plan the entrance hall of Phillip's house is shown absorbed into the room to its east to create the dining room, although whether removal of this key structural element had been carried out or was merely intended is unknown. It certainly existed in its original form by the time of Macquarie's arrival.

[media]In 1845 a more detailed plan was prepared for the report recommending the house's demolition. The three-room configuration of the original house is shown – either reinstated or never changed – although the front door has been relocated into what was originally the east room. The thick rear wall of the original house can be clearly seen. To the rear of Governor King's drawing room is Macquarie's bow-fronted dining room, or 'Great Saloon', its distinctive rear wall so easily identifiable when uncovered by archaeologists, with his other additions to the east. To the south-west stands the kitchen wing, linked to the house proper by a covered way. It was substantially repaired or rebuilt after a fire in 1840. Beyond this are the new privies built south of the main outbuildings in 1837, and a row of what appear to be weatherboard stables and servants' rooms.

This rather inadequate plan lacks either scale or orientation. Confusingly, the upper floor is shown on the same sheet at right angles to the ground floor, presumably to save paper – although there are no stairs to access the upper floor anyway. Perhaps some of the deficiencies of this plan can be explained by the fact that there was never really any doubt about the house's destiny.

The later additions for Governor Darling, in particular, are thought to have destabilised the structure. Otherwise, architectural historians believe that Phillip's house, with its 'good foundation', could still be standing.[20] Regardless of its structural integrity, however, its survival was unlikely. It stood in the way of Sydney's progress, a fact that had been long lamented.

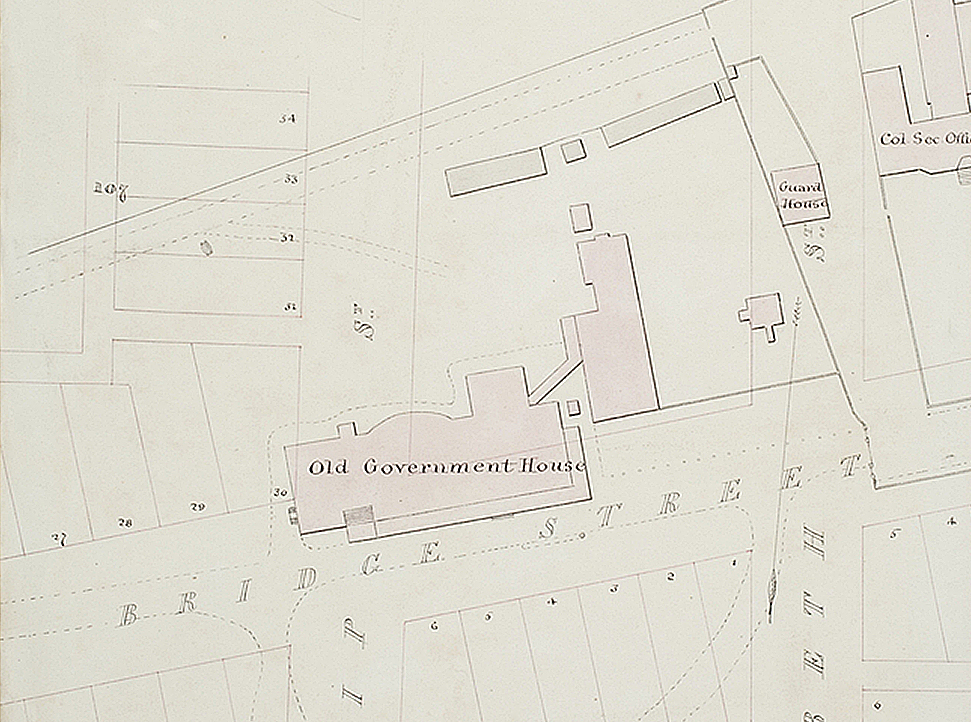

[media]A plan discovered in 2009,[21] which also accompanied the 1845 report, starkly reveals the fate of the 'Old' Government House: it, and its drive, paths and gardens are shown clearly overlaid with streets and allotments. Following the occupation of the new – and current – Government House in June, demolition was approved and by January 1846 the greater part of the house had been demolished. Phillip's original building and those portions interfering with the extension of Bridge Street had been cleared away by March, the east wing had been removed by May, and by December 1846 the 'old' Government House had nearly disappeared.

Today any remains of the front rooms of Phillip's house, the cellars and verandah, Governor King's long drawing room, and Greenway's addition, lie beneath the footpaths and traffic of Bridge and Phillip Streets. Although the land was cleared, the core site remained remarkably unscathed despite various redevelopment proposals. Terraces were built on Young and Phillip Streets, a carter's yard with associated cottage and sheds occupied the site, advertising hoardings and small sheds used as shops appeared on the perimeter, and a two storey corrugated iron 'tin shed' for the Government Architect's Department was constructed, but physical remains of the house itself, and a wealth of artefacts, still lay hidden below.

Rediscovery and recognition

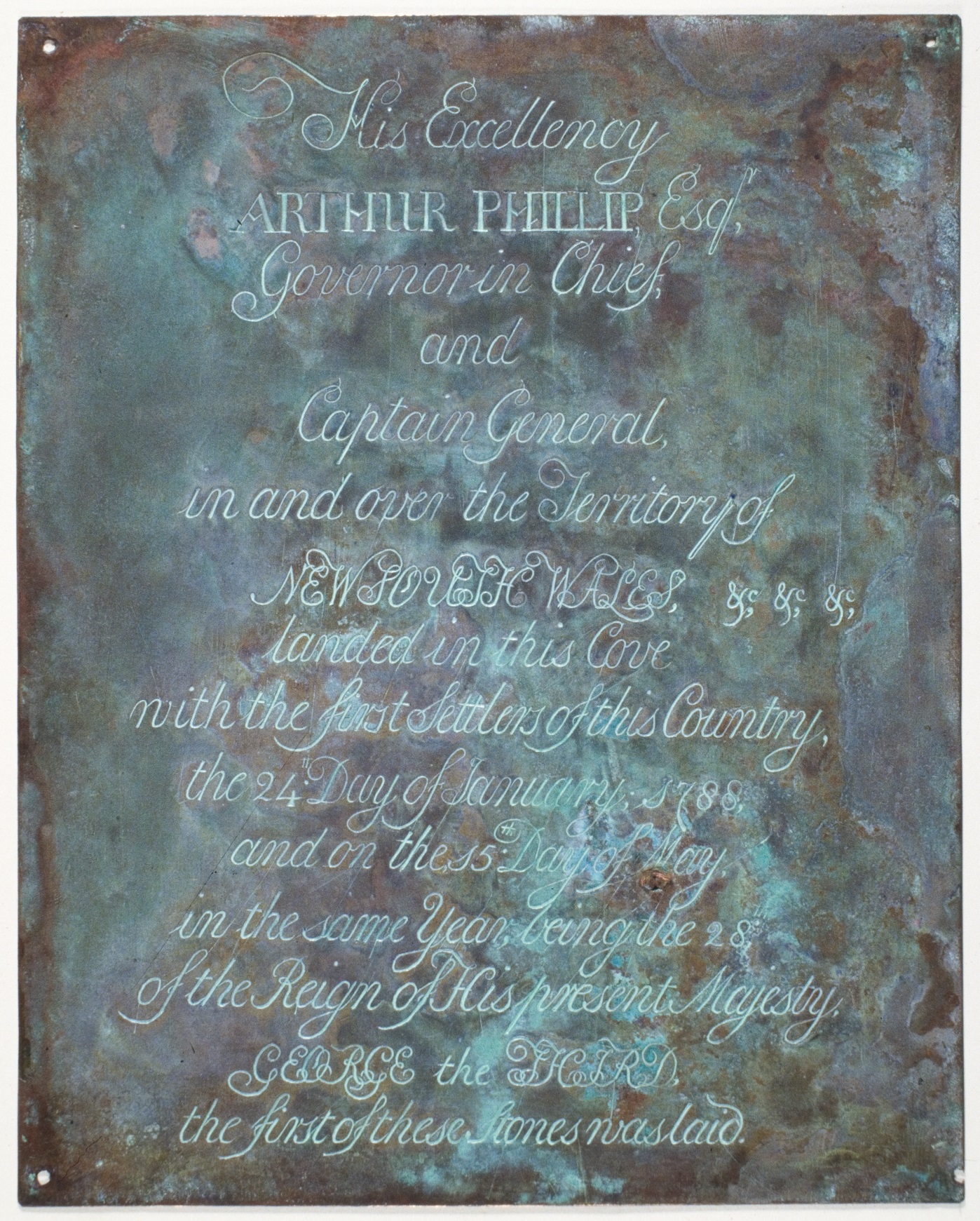

[media]On 6 March 1899 the engraved copper foundation plate laid by Governor Phillip in May 1788 (now on display in the Museum of Sydney) was unearthed beneath the Bridge Street footpath by a man working on the telephone tunnel system. Its discovery, with part of the southern or back wall of Phillip's original house, helped to remind Sydneysiders of the existence of the first Government House and proved invaluable in the 1980s in establishing its precise location.

In 1919 the significance of the site was recognised by the Royal Australian Historical Society with a commemorative tablet and stone pedestal at the corner of Phillip and Bridge Streets – now in Phillip Street. The Society's president explained,

…this spot had been the very centre of social, political, and industrial life in Australia. Here Arthur Phillip had been beset by his many difficulties, and from here he had started out on his many expeditions…

[media]This marks the start of a list of the many 'stirring events' associated with the place which the president hoped the tablet would prompt passers-by to reconstruct in their imaginations.[22]

[media]Renewed plans for large-scale development of such valuable real estate in the heart of the city – and a growing interest in our history leading up to the bicentennial – saw government, commercial and public attention return to the site, by then a car park. In 1982, a call for development proposals for the land, and resultant planned 38-level tower block, provoked community concern and led to the decision that archaeological investigations should precede any work.

[media]In February 1983 archaeologists uncovered the rear wall and footings of the first Government House – two wide parallel rows of sandstone blocks with locally made bricks and pipeclay mortar. The discovery of Phillip's 'good foundation' – tangible evidence of the first year of European settlement – ultimately led to the preservation of the site.

Remembering the house

'The First Governor – a Bicentenary Symposium on Arthur Phillip', was held at the Museum of Sydney on the site of first Government House on the corner of Phillip and Bridge streets in September 2014. The aim of the symposium was to remember Phillip and his legacy – something that has a long history in New South Wales, with varying degrees of accuracy and embroidery. In the second half of the nineteenth century an image appeared which was also about significance and memory…or rather misremembering.

[media]An engraving of a recently-demolished 'ricketty-looking shanty' was published in The Illustrated Sydney News on 16 July 1864, entitled '"Government House," in the days of Governor Phillip’. The image – a view of a humble cottage in Pitt Street – represents a persistent myth. Variations of it appeared in the press for some 50 years, along with accompanying 'facts' and tales and discussions about what the first Government House, or houses – there seems to have been some dispute about just how many Government Houses there were – represented.[23]

[media]The discovery of the foundation plate in 1899 inspired a flurry of correspondence. Claim and counter-claim prompted one frustrated letter writer to comment:

It would certainly appear…that the first Government House was a very restless sort of edifice, and constantly on the move, and goodness only knows how many more sites it occupied in the course of its peregrinations before finally settling down.[24]

I think we can all be grateful that the first Government House finally 'settled down', and its site has been preserved for us all to enjoy.

This essay is based on a paper originally presented at The first governor – A bicentenary symposium on Arthur Phillip, held at the Museum of Sydney on the site of first Government House on 5 September 2014 by Sydney Living Museums to commemorate the bicentenary of Arthur Phillip’s death

References

James Broadbent, The Australian Colonial House: Architecture and Society in New South Wales 1788–1842. Sydney: Hordern House in association with the Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, 1997.

Joy Hughes, ed, First Government House Site in the 20th Century. Glebe, NSW: Historic Houses Trust of NSW, 1995.

Jane Kelso, 'Modelling the first Government House'. Insites (Spring, 2010), republished on the Sydney Living Museums website, https://sydneylivingmuseums.com.au/stories/modelling-first-government-house , viewed 16 May 2018. A scale model of the first Government House is also on display at the Museum of Sydney on the site of first Government House, cnr Phillip and Bridge streets, Sydney.

Helen Proudfoot, Anne Bickford, Brian Egloff and Robyn Stocks. Australia's First Government House. Sydney: Allen & Unwin in conjunction with the Department of Planning, 1991.

For important images showing the evolution of the house, its garden and the early settlement, see the Natural History Museum, UK, 'First Fleet Artwork Collection’, http://www.nhm.ac.uk/nature-online/art-nature-imaging/collections/first-fleet/artcollection/index.dsml, viewed 1 December 2014.

In particular, for a depiction of the house and its compound, outbuildings and gardens, including Phillip's relocated portable house with blue panels framed in white, see: Port Jackson Painter, A View of Governor Philips [sic] House Sydney Cove Port Jackson taken from NNW, c1792, 'The Watling Collection’. Watling Drawing – no 19.

Notes

[1] Francis Fowkes (attrib), Sketch & Description of the Settlement at Sydney Cove Port Jackson in the County of Cumberland taken by a transported Convict on the 16th of April, 1788, which was not quite 3 Months after Commodore Phillips’s Landing there, FF delineavit, Neele sculpt, published by R Cribb, London, 24 July 1789. National Library of Australia MAP NK 276

[2] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales; With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, vol 1, 1798, edited by Brian H Fletcher (Sydney: AH & AW Reed in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, 1975), 17

[3] Artist unknown, Sketch of Sydney Cove, Port Jackson, in the County of Cumberland, New South Wales. July 1788, The National Archives of the UK (TNA): MPG 1/300

[4] Governor Phillip to Lord Sydney, 9 July 1788, Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 1, part 2, 147

[5] Governor Phillip to Lord Sydney, 12 February 1790, Historical Records of Australia, Series 1, vol 1, 143

[6] Arthur Phillip, The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay; with an Account of the Establishment of the Colonies of Port Jackson & Norfolk Island; compiled from Authentic Papers, which have been obtained from the several Departments. to which are added The Journals of Lieuts Shortland, Watts, Ball, and Capt Marshall with an Account of their New Discoveries (London: John Stockdale, 1789), 125

[7] Watkin Tench, Sydney's First Four Years; being a reprint of A narrative of the expedition to Botany Bay and A complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson, with an introduction and annotations by LF Fitzhardinge (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1979), 140

[8] Mr Bartum, Proceedings of A General Court-Martial, held at Chelsea Hospital, Which commenced on Tuesday, May 7, 1811, and continued by Adjournment to Wednesday, 5th of June following, for the trial of Lieut.-Col. Geo. Johnston, Major of the 102d Regiment, late the New South Wales Corps, on a charge of mutiny, (While Major George Johnston, Captain of the said Corps, then under his Command, and doing Duty at Sydney, in the Colony of New South Wales;) exhibited against him by the Crown, for deposing On the 26th of January, 1808, William Bligh, Esq. F.R.S. then captain in His Majesty's Navy, (and since appointed Rear-Admiral of the Blue,) Captain-General and Governor-in-Chief in and over the said territory of New South Wales and its dependencies (London: Sherwood, Neely and Jones, 1811), 369

[9] Artist unknown, The Arrest of Governor Bligh, 1808, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, ML Safe 4/5, available online at http://archival.sl.nsw.gov.au/Details/archive/110322230, viewed 16 May 2018

[10] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales; With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, vol 1, 1798, edited by Brian H Fletcher (Sydney: AH & AW Reed in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, 1975), 152

[11] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales; With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, vol 1, 1798, edited by Brian H Fletcher (Sydney: AH & AW Reed in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, 1975), 90

[12] Watkin Tench, Sydney's First Four Years; being a reprint of A narrative of the expedition to Botany Bay and A complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson, with an introduction and annotations by LF Fitzhardinge (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1979), 140

[13] Mortimer William Lewis, Colonial Architect, Report upon the present State of the Old Government House, Sydney, 1 August 1845, Enclosure in Report of a Board appointed by His Excellency the Governor to examine the state of the Old Government House, 15 September 1845. State Archives and Records NSW: Colonial Secretary; NRS 905, Main series of letters received, 1826-1982 [4/2717.2] Letters received from Colonial Architect, 1846

[14] Governor Bourke to Lord Goderich, 2 November 1832, Historical Records of Australia, Series 1, vol 16, 785

[15] Ralph Darling to RW Hay, 26 July 1826, The National Archives of the UK (TNA): CO 323/146, f191. (Colonial Office. Colonies General. Original Correspondence, Private Letters to Mr Hay: Ceylon, Mauritius, New South Wales, Tasmania, India, 1825–6)

[16] Governor Bourke to Viscount Goderich, 28 February 1832, Historical Records of Australia, Series 1, vol 16, 1914-25), 539

[17] Governor Macquarie to Earl Bathurst, 12 December 1817, Historical Records of Australia, Series 1, vol 9, 719

[18] Under Secretary Hay to Mr A Y Spearman, 27 July 1837, Historical Records of Australia, Series 1, vol 19, 111–12

[19] Artist unknown, Ground Floor of the Front rooms of Government House Sydney, c1807, The National Archives of the UK (TNA): CO 201/44, f37. (Colonial Office. New South Wales. Correspondence, Original – Secretary of State. Port Jackson: Despatches, 1807)

[20] For example, Dr James Broadbent AM, interviewed by the author, 21 April 2010

[21] Surveyor General's Office, Plan of Streets intersecting at Old Government House, enclosed in Report of a Board of Survey 15 September 1845. Dixson Map Collection, State Library of NSW: CA 84/30 (formerly located at DL Add 193), http://digital.sl.nsw.gov.au/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?embedded=true&toolbar=false&dps_pid=FL3800771, viewed 16 May 2018

[22] Daily Telegraph, 31 October 1919, 6; Sydney Mail, 5 November 1919, 14

[23] For example: The Illustrated Sydney News, 16 July 1864, 9; The Illustrated Sydney News, 26 January 1888, 14; The Illustrated Sydney News, 20 December 1890, 6; The Illustrated Sydney News, 13 January 1894, 13; Evening News, 11 March 1899, 1; The Sydney Mail, 25 March 1899, 686; The Australian Town and Country Journal, 23 June 1900, 34

[24] AG [Arthur George] Foster to the Editor, Sydney Morning Herald, 18 March 1899, 12