The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The beginnings of Anzac Day commemorations in Sydney

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The beginnings of Anzac Day commemorations in Sydney

[media]The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) was formed in 1915 from troops of the First Australian Imperial Force and the First New Zealand Expeditionary Force. The troops were known as Anzacs. Their landing at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915, as part of a British and Allied campaign to capture the Gallipoli Peninsula and open the Dardanelles for the Allied navies, was the first major military action fought by Australian and New Zealand forces during World War I. The significance of this moment, and the devastating losses of troops, led to movements to commemorate it.

The idea of Anzac Day

The earliest use of the term and concept of 'Anzac Day' probably occurred in Adelaide on 13 October 1915, when the South Australian Government authorised 'a patriotic procession and carnival' to temporarily replace the traditional Eight Hours Day celebration. The name 'Anzac Day,' was chosen through a competition, and was suggested by Robert Wheeler, a draper of Prospect. [1] Melbourne observed an Anzac Remembrance Day on 17 December 1915. [2] Both of these days were used to raise funds to provide comforts for soldiers. The Mayor of Brisbane organised a public meeting in January 1916 to discuss commemorating Anzac Day that April, where it was resolved 'it was desirable that the first anniversary of the landing at Gallipoli should be suitably celebrated in this State, and that other States of Australia be invited to consider similar action.' [3] This idea soon expanded to include a public holiday, of solemn observance. [4]

The idea of Anzac Day in Sydney

In Sydney, the idea of commemorating Anzac Day on 25 April 1916 appears to have occurred to many people at the same time. Sydney City Council began discussing the commemoration of the first anniversary of Anzac in February 1916. At a meeting of the Sydney City Council Finance Committee, Alderman James Joynton Smith said he was in favour of commemorating the day, as 'there was no doubt Anzac Day would ultimately become one of the great days in the calendar of the British Empire.' The Sydney Morning Herald reported:

The Lord Mayor said that the imperishable glory achieved at Anzac had opened a new page in Australian history. He considered that the commemoration should not only cover the metropolis, but the State, and the whole Commonwealth — hear, hear — and advised the council, before doing anything, to see what the State Government proposed. The council would, of course, co-operate with the Government. [5]

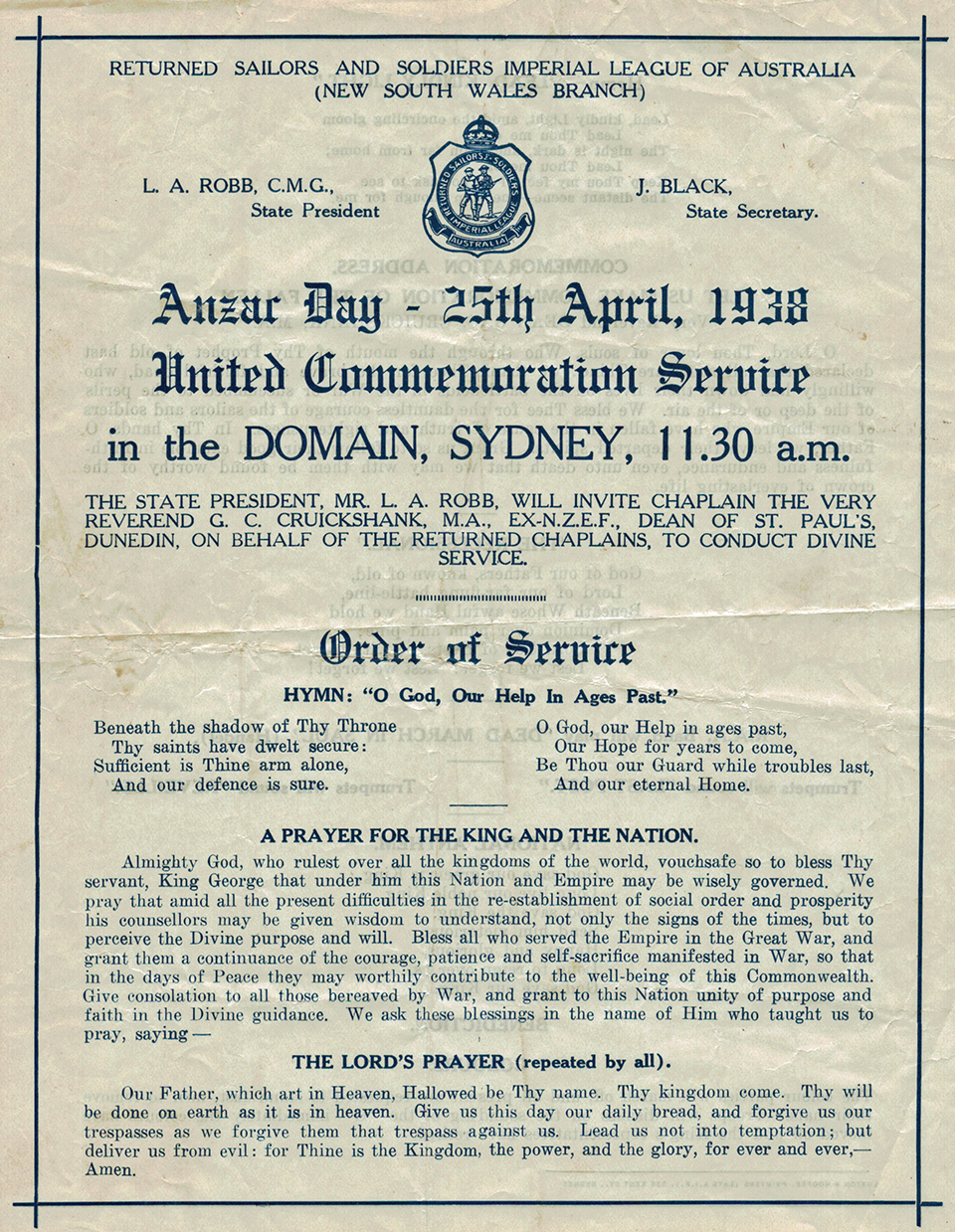

In March, [media]the Shakespeare Tercentenary Memorial Fund, in cooperation with the Returned Soldiers' Association, resolved to organise a concert evening at Town Hall on Tuesday 25 April 1916. [6]

On 29 March, Premier WA Holman announced the Government supported the idea of a national commemoration, including church services and a minute's silence, and was keen to see the day devoted to fundraising for a memorial, and recruiting. He also said 'the whole of the arrangements' had been placed in the hands of the Returned Soldiers' Association. [7] The Returned Soldiers Association embraced the idea heartily:

"We want to get going now," said the secretary of the Returned Soldiers Association when seen last night. "We really want Anzac Day to be a memorable national event. It will comfort all of us to see the boys who have died fittingly remembered. And it will cheer us more than I can say if we can make the big recruiting rally at night what we want it to be." [8]

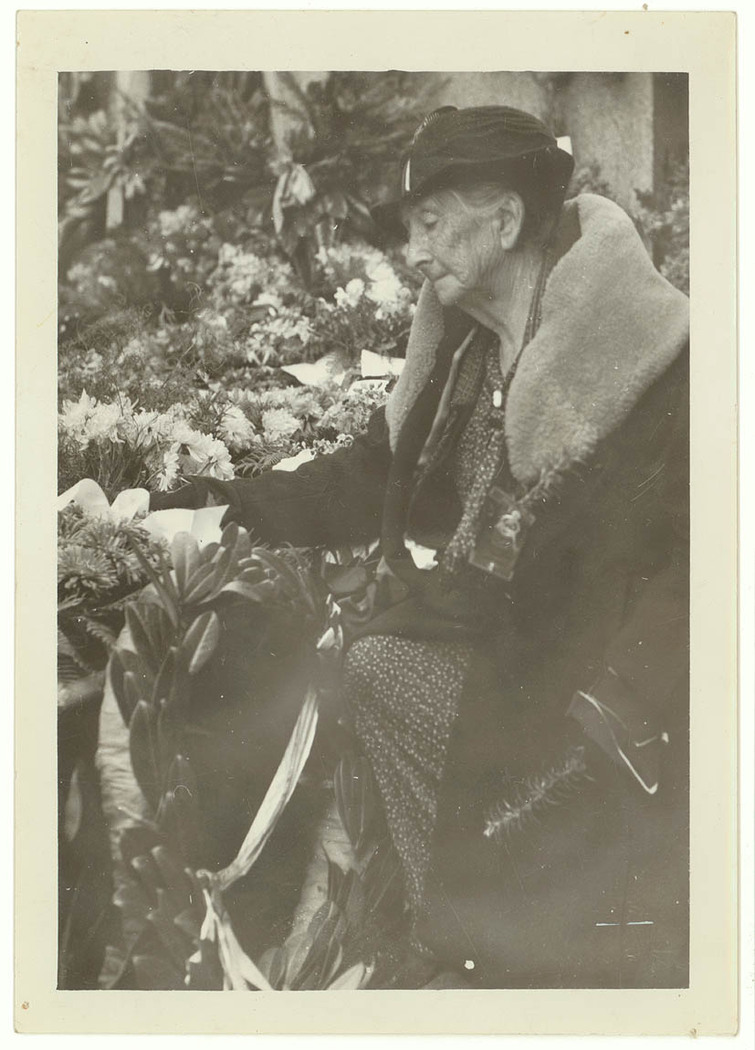

Numerous correspondents to the newspapers dissented from these ideas. Some urged that the money spent on illuminations could be better spent on supporting wounded soldiers and bereaved families. Others argued, in vain, that celebrations should wait until the war's end and the day should be an occasion for the expression of grief and regret about the loss of life and the casualties of war. Their view was that Anzac Day, rather than being an occasion for joy and celebration, should be marked only by quiet contemplation and by prayers for peace and for the fallen. [9]

The first Anzac Day

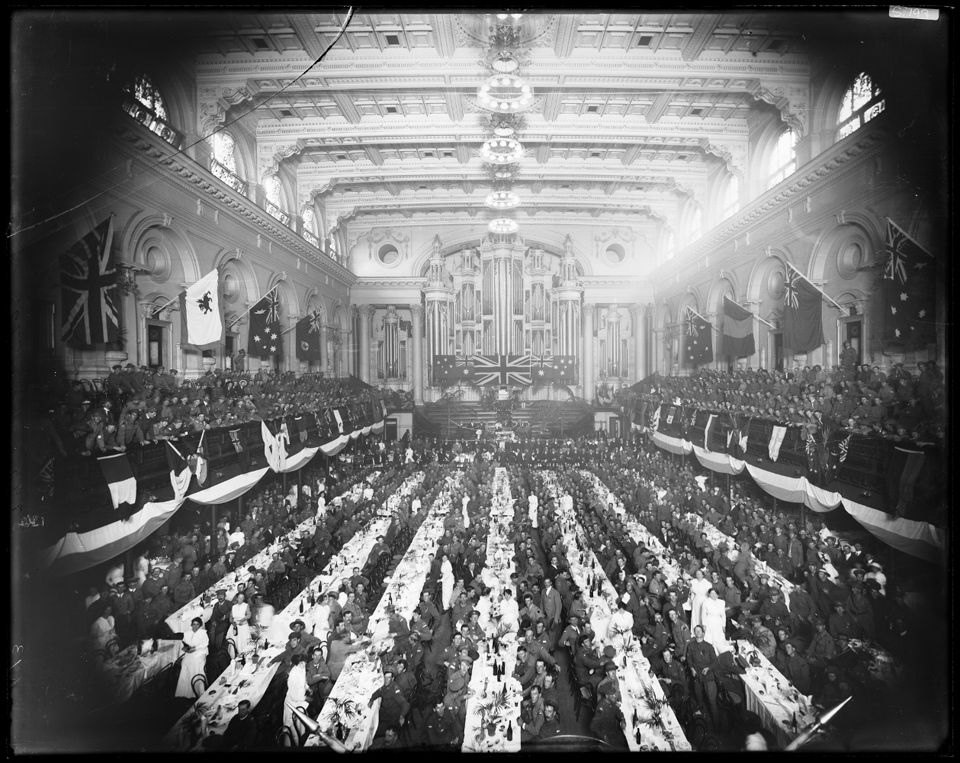

Sydney's first Anzac Day proceeded on 25 April 1916. At nine in the morning every train and tram was brought to a standstill 'in order that the passengers may give three cheers for the King, the Empire, and the Anzacs.' [10] At 10am, 5,000 returned soldiers paraded through the city. All government offices, and many business firms, closed from 11:30am until 2pm to enable staff to attend a combined commemoration service in the Domain, or memorial church services. One minute's silence was declared at noon. [media]The Lord Mayor entertained the troops at a luncheon, and various theatres held matinee performances. Returned soldiers assisted with recruiting campaigns in city and suburbs. The Governor-General, the Governor, the Premier and the Lord Mayor attended a commemoration concert in the Town Hall in the evening. Throughout the day, ladies collected contributions from the public towards the Anzac Memorial Fund, raising more than £5,000 to erect a soldiers' memorial hall in the city, where returned men could meet for social purposes and obtain support and assistance. [11]

For the duration of the war, Anzac Days followed this form – a minute's silence at 1pm, church services, and a march of troops through the city to a large military memorial service in the Domain, or the Agricultural Society's Showground at Moore Park. After 1917 the Obelisk on Anzac Parade, near Moore Park, was the focus for Anzac Day observances. Recruiting remained a feature of the day. Suburban ceremonies also developed, many coinciding with the unveiling of memorials to honour local men who had served or fallen.

Anzac Day in peacetime

[media]Australian troops did not return to great victory parades. This was partly because their arrival home depended on available shipping, but also because of the influenza epidemic of 1919, which prevented people assembling in large numbers. The 1919 parade through Sydney was cancelled as a result, but a public commemorative service was held in the Domain. Participants were required to wear masks and stand three feet apart. [12]

[media]The 25th day of April was declared a national holiday in 1920, though it was not observed in every state until 1927, partly because of opposition from businesses who were fearful of its effect on profits. [13] In 1929, when the Cenotaph was unveiled in Martin Place, ceremonies moved into the city.

[media]In the early 1920s returned soldiers mostly commemorated Anzac Day informally, primarily as a means of keeping in contact with each other, rather than in a major public way. [media]But as time passed and they inevitably began to drift apart, the ex-soldiers perceived a need for an institutionalised reunion. Anzac Day began to take on a distinct form. Marches, by now traditional across Australia, were followed by a service of commemoration at the memorial, after which the soldiers would disperse to clubs or hotels for refreshments and reminiscences.

The Dawn Service at the Cenotaph dates from 1931, although since 1928 there had been less formal gatherings of returned servicemen at dawn on Anzac Day to coincide with the time of the 1915 Gallipoli landings. [14]

Further reading

Anzac Day. Australian War Memorial. Viewed 3 December 2014. http://www.awm.gov.au/commemoration/anzac-day.

KS Inglis. Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008. First published 1998.

Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds. What's Wrong With Anzac?: The Militarisation of Australian History. University of New South Wales: University of New South Wales Press, 2010.

Notes

[1] The Register, 27 August 1915, viewed 10 December 2014, http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/59420501

[2] 'Remembrance Day,' The Age, 18 Dec 1915, viewed 10 December 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article154921485

[3] 'ANZAC,' The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 January 1916, viewed 10 December 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article28107868

[4] 'Anzac Day,' The Sydney Morning Herald, 1 March 1916, 14, viewed 10 December 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15669741

[5] '"Anzac Day"', The Sydney Morning Herald, 24 February 1916, 9, viewed 10 December 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15653561

[6] 'Anzac Day. Patriotic Celebration. Shakespeare Tercentenary,' The Sydney Morning Herald, 18 March 1916, viewed 10 Dec 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15667365

[7] 'Anzac Day,' The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 March 1916, viewed 10 December, 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15652222

[8] 'Anzac Day,' The Sydney Morning Herald, 31 March 1916, viewed 10 December, 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15661005

[9] The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 March 1916: 13; 30 March 1916: 12; 1 April 1916: 8; 11 April 1916: 4; 18 April 1916; 4

[10] The Sydney Morning Herald, 24 April 1916: 6

[11] The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 April 1916: 12; 13 April 1916: 8; 27 April 1916: 9

[12] The Sydney Morning Herald, 18 April 1919: 4

[13] Business, through the Chamber of Commerce, the Master Retailers Association and other groups, lobbied for Anzac Day to be commemorated on the nearest Sunday to 25 April ('Anzac Sunday') while the returned services organisations and the trade unions sought a public holiday on 25 April each year. The Premiers Conference in 1923 agreed that Anzac Day should be celebrated consistently on 25 April. The Sydney Morning Herald, 26 May 1923: 13

[14] The Sydney Morning Herald, 26 April 1928: 11; 26 April 1929: 12; 26 April 1930: 14. The 1931 service was the first attended by the Governor and representatives of state and federal governments etc. The Sydney Morning Herald 27 April 1931: 10.

.