The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Sydney’s Oldest Unsolved Murders

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Serious crimes and minor offences

On 11 February 1788, the first convict court in the colony of New South Wales opened for business. Captain David Collins and the six officers adjudicating (‘three senior naval officers and three military officers’), dealt with one charge of assault and two charges of theft.[1] Minor sentences were handed out.

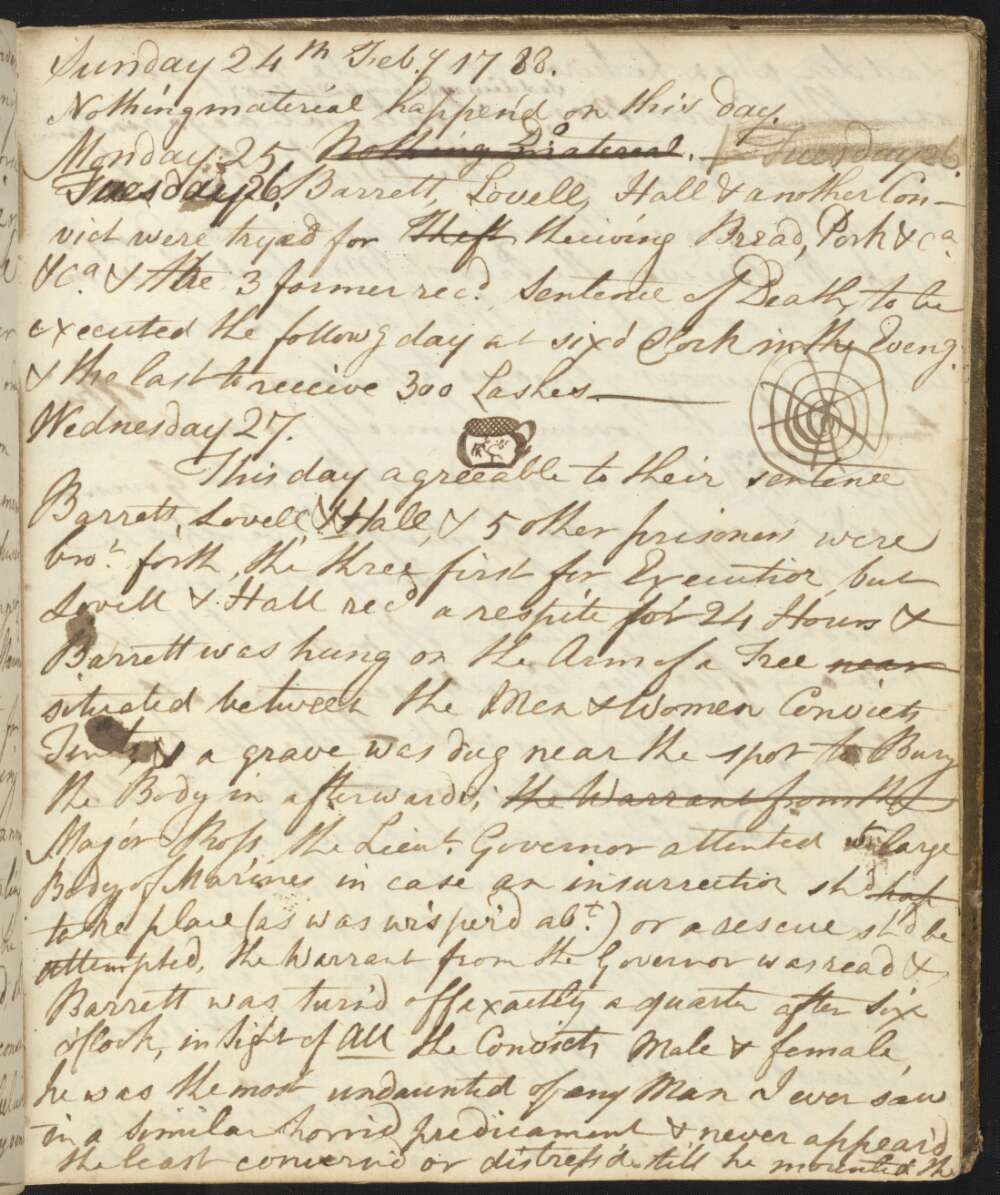

[media]Just over two weeks later a more serious punishment was ordered and Thomas Barrett became the first person hanged in the colony.[2] Barrett was convicted, alongside three other men, of stealing precious food provisions. Barrett, Henry Lavell and Joseph Hall were sentenced to death while John Ryan was to receive 300 lashes. The sentences of death were read out at one o’clock on the afternoon of 27 February 1788, and Barrett, in an example of how quickly the justice system moved in the early days of New South Wales, was hanged just hours later. Lavell, Hall and Ryan were all given reprieves, but a brutal punishment had been determined and delivered just one month and one day after the motley members of the First Fleet set up camp on land.[3]

Minor and serious infractions of the laws brought with the colonists from Britain continued to plague the settlement. Theft was an especially common crime as was another common, and highly disruptive, issue for the colonists: public drunkenness. Indeed, gross intoxication led to several ‘ugly brawls in which serious physical injury was sustained by some of the participants’.[4]

With colonisation came numerous acts of violence inflicted upon the First Nations people, including murder. It was several years, however, before murders were committed in Sydney by the colonists upon each other.

Murder

In late October 1788 a marine, James Rogers, went missing and, while a convict was taken into custody in relation to the disappearance, no charges were laid.[5] In November 1788, an unnamed man became the first soldier in the colony to meet an untimely, non-work related end. He ‘died at the hospital of the bruises he received in fighting with one of his comrades, who was, with three others, taken into custody and afterward tried upon a charge of murder’. The men responsible for the unexpected death were found guilty of manslaughter rather than murder with ‘each sentenced to receive two hundred lashes’.[6]

On 5 October 1794 Simon Burn, who had arrived on the First Fleet as a convict, became the first free man in the colony to be murdered by another colonist. Burn had been drinking with John Hill at Parramatta when, in an effort to prevent Hill from beating a woman with whom he cohabitated, he was stabbed in the 'heart with a knife’.[7] Hill was charged with having ‘feloniously, wilfully, & of his Malice aforethought' made an assault 'with a certain Knife of the value of sixpence’ on Burn on 13 October 1794 and was hanged for murder on 16 October 1794.[8]

The historical record reveals some clues in relation to the many who went missing, those who were manslaughtered and those who were murdered. Some cases, such as the murder of Burn, were brought to a neat and speedy conclusion. But not all of the early murders committed by the colonists upon each other were solved. This is a reflection of the very limited resources of the place and time, the primitive investigative techniques in use during the colonial period and a general lack of the types of scientific knowledge we take for granted today.

A Watchman, April 1793

The month of April 1793, in Sydney Cove, has been described as a period in which ‘garden robberies continued with great frequency.’[9] David Collins recorded that in the same month – just over five years after the First Fleet arrived – a much more serious crime might have been committed, as some people:

… were taken up at Parramatta on suspicion of having murdered one of the watchmen belonging to that settlement; the circumstances of which affair one of them had been overheard relating to a fellow-convict, while both were under confinement for some other offence. A watchman certainly had been missing for some time past; but after much inquiry and investigation nothing appeared that could furnish matter for a criminal prosecution against them.[10]

A soldier, ‘sentenced by a court-martial to receive three hundred lashes’, made a confession in relation to the missing man, but later admitted he knew nothing about the watchman’s fate and ‘had accused himself of perpetrating so horrid a crime soley in the hope of deferring his punishment’.[11] Historian John Cobley notes the potential crime – ‘a watchman was missing believed murdered at Parramatta’ – in a list of crimes committed over the month of April 1793.[12]

If the watchman stationed out at Parramatta was a victim of foul play as believed this could be Sydney’s, and Australia’s, first murder of a colonist and, being unsolved, could also claim the status of the country’s oldest unsolved murder. The matter certainly attracted more attention than the missing soldier of 1788, with Collins commenting on the missing watchman again in the early days of 1794:

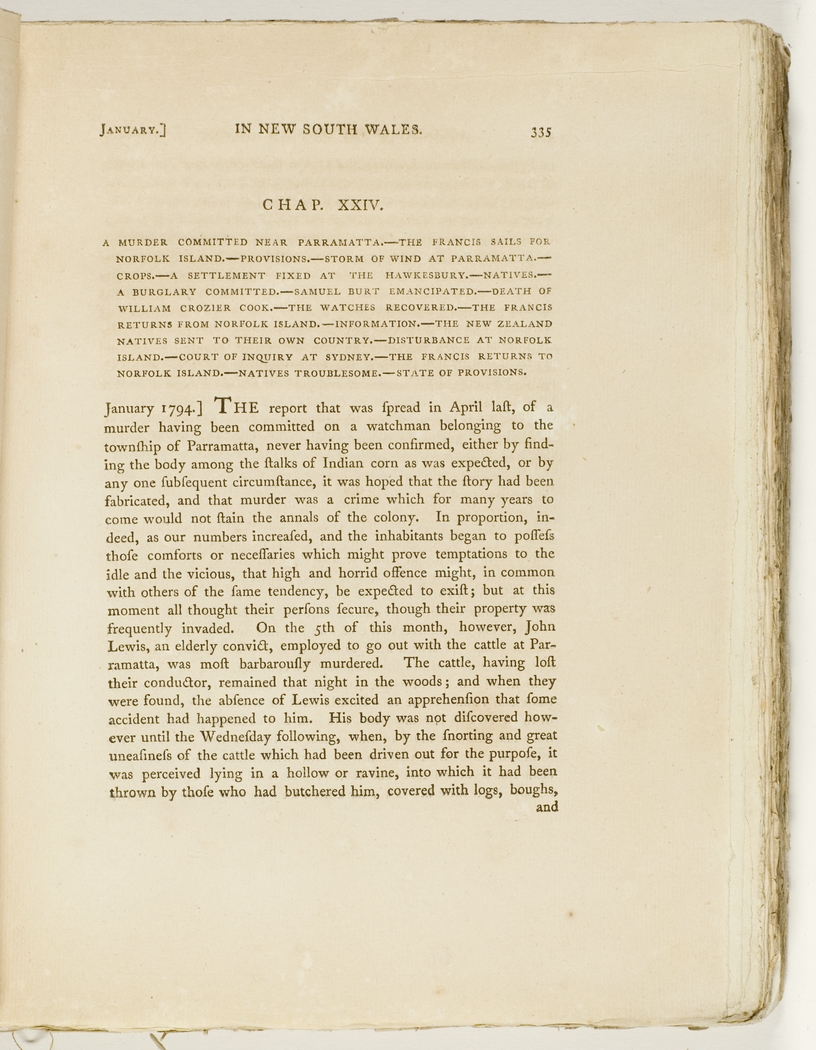

The report that was spread in April last, of a murder having been committed on a watchman belonging to the township of Parramatta, never having been confirmed, either by finding the body among the stalks of Indian corn as was expected, or by any one subsequent circumstance, it was hoped that the story had been fabricated, and that murder was a crime which for many years to come would not stain the annals of the colony.[13]

John Lewis, January 1794

[media]The first convict in the colony who is believed to have definitely been a victim of murder, dying at the hands of his fellow colonists, was the elderly John Lewis. An enthusiastic gambler, Lewis regularly boasted of how he kept all of his illicit earnings stitched within his clothing.[14] It is highly likely that the possibility of sudden wealth precipitated Lewis’ violent end. Lewis disappeared on 5 January 1794:

… an elderly convict, employed to go out with the cattle at Parramatta, was most barbarously murdered. The cattle, having lost their conductor, remained that night in the woods; and when they were found, the absence of Lewis excited an apprehension that some accident had happened to him. His body was not discovered however until the Wednesday following, when, by the snorting and great uneasiness of the cattle which had been driven out for the purpose, it was perceived lying in a hollow or ravine, into which it had been thrown by those who had butchered him, covered with logs, boughs, and grass. Some native dogs, led by the scent of human blood, had found it, and by gnawing off both the hands, and the entire flesh from one arm, had added considerably to the horrid spectacle which the body exhibited on being freed from the load of rubbish which had been heaped upon it…[15]

A post-mortem was conducted by the Assistant Surgeon Thomas Arndell.[16] Richard Atkins, a magistrate, wrote in his journal of a ‘most atrocious murder’ and noted that the victim, who had been ‘buried under some wood’, had a cut throat and that there were ‘two stabs in his side’.[17]

Lewis was buried at St John’s Cemetery, Parramatta on 9 January 1794, the day after his body was found.[18] Some brief inquiries were made in an attempt to identify those who were responsible for the incredibly violent crime, but it was decided by authorities that ‘until some riot or disagreement among [the perpetrators] should occur, no clue would be furnished that would lead to their detection'.[19]

Joseph Luker, August 1803

Another unsolved murder case is the killing of Constable Joseph Luker, bludgeoned to death on the night of 26 August 1803.[20] An ex-convict, Luker was declared a free man in 1796 and joined the colony’s fledgling police force.[21] As a Constable, Luker was investigating the theft of a small, portable desk when he was attacked near modern-day Macquarie Street. The assault was brutal, with various weapons used against Luker including the stolen desk, the frame of a wheelbarrow, his own cutlass and cutlass guard. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser reported:

The velocity with which the necessary measures of Enquiry were adopted, could only be equalled by the Public Anxiety to discover the Perpetrators of the inhuman act.[22]

Two of Luker’s colleagues, ex-convicts Constables William Bladders and Isaac Simmonds were charged with wilful murder, but found not guilty. Constable John Russell was indicted for breaking and entering, but found not guilty due to insufficient evidence. Known thief Joseph Samuels was also indicted for breaking and entering. Samuels confessed to the robbery of the desk, but not to the murder of Luker. Another known thief, Richard Jackson also confessed to robbery and, as a witness for the Crown, implicated Samuels, before being declared innocent of any wrongdoing.

Samuels was convicted of robbery on 20 September 1803. Simmonds, ‘a convicted thief with a known propensity for violence’,[23] continued to attract so much suspicion in relation to the case that he was ‘purposely brought from George’s Head to witness the awful end of the unhappy culprit’[24] on the day of Samuels’ scheduled execution. His presence was a reminder that he only escaped the noose ‘from the want of that full and sufficient evidence which the Law requires’.[25] Famously, Samuels became known as ‘the man they could not hang’ with his sentence commuted to secondary transportation when the hangman’s rope, on 26 September 1803, failed three times.[26]

This murder was the first crime to be serialised by a local publisher for a Sydney-based reading public,[27] with The Sydney Gazette dedicating thousands of words to telling the story of a murder that shook the young city. The case remains unsolved to this day and has been referred to as the city’s, and the country’s, oldest cold case.[28]

The first?

Asserting a claim of ‘the first’ of anything can often be contentious. For example, the title of Australia’s first serial killer has been given to various offenders with solid arguments made for: Alexander Pearce ‘The Cannibal Convict’ who ate fellow convicts who dared to escape their penal confines with him and who was hanged in Hobart Town in 1824;[29] murderer, and Jack the Ripper suspect, Frederick Deeming who was hanged in Melbourne in 1892;[30] as well as Frank Butler, who lured men into the Blue Mountains so that he could kill them, who was hanged for his crimes in Sydney in 1897.[31] More recently the title has been given to William MacDonald ‘The Mutilator’ who viciously murdered five people in Brisbane and Sydney in the early 1960s and was imprisoned for life in Sydney in 1963.[32]

Similarly, identifying Australia’s oldest case of unsolved murder is not necessarily a straightforward task. It is possible that the missing marine of 1788 and the missing watchman of 1793 both met violent ends, but no bodies were ever found and no cases were ever built for murder or for manslaughter. Limited contemporaneous efforts were invested into the murder of John Lewis which, as a crime still unresolved, holds an obvious and strong claim for the title of Sydney’s oldest unsolved murder case. Constable Joseph Luker could also be noted as Australia’s oldest unsolved murder case because, unlike Lewis, there were quite extensive and very thorough investigations that saw every effort exerted to identify and punish those responsible. Luker’s story is, certainly, the story of the first officer of the law to be killed in the line of duty in New South Wales and his murder remains an important marker on the timeline of early policing in Sydney.

Both Lewis and Luker were shipped to New South Wales as convicts (it is possible that they both came out on the Atlantic with the Third Fleet, arriving in Australia on 20 August 1791).[33] Though just two convicts of many, it is highly likely that these men, in such a small settlement and with their criminal pasts, knew each other. What could certainly not have been predicted when they set sail for the far side of the world, was their soon to be shared status as victims of Australia’s oldest unsolved murders.

Notes

[1] John Cobley, Sydney Cove, 1788. (1962; repr., Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1980), p67; David Collins, An Account of the English Colony of New South Wales (1798; repr., Adelaide: Libraries Board of South Australia,1971), 9.

[2] Jim Main, Hanged: Executions in Australia. (Seaford: Bas Publishing, 2007), p9; Steve Samuelson and Ray Mason, A History of Australian True Crime. (North Sydney: Ebury Press, 2008), p12

[3] John Cobley, Sydney Cove, 1788. (1962; repr., Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1980), pp87-88; Catherine Gilbert, Capital Punishment in New South Wales. (Sydney: New South Wales Parliamentary Library), p1; Arthur Bowes Smyth, 'A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China in the Lady Penrhyn, Merchantman William Cropton Server, Commander by Arthur Bowes Smyth, Surgeon – 1787–1788–1789'. c1790, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales (Call No.: ML SAFE 1/15), pp106-108

[4] Bruce Swanton, A Chronological Account of Crime, Public Order & Police in Sydney 1788-1810. (Phillip: Australian Institute of Criminology, 1983), p12

[5] John Cobley, Sydney Cove, 1788. (1962; repr., Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1980), pp87-88

[6] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony of New South Wales. (1798; repr., Adelaide: Libraries Board of South Australia, 1971), pp46-47

[7] John Cobley, Sydney Cove, 1793-1795: The Spread of Settlement. (Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1983), p190; Samuel Marsden in J.J. McGovern, The Story that the Graveyards Tell, Catholic Weekly 25 September 1952, pp7, 12

[8] John Cobley, Sydney Cove, 1793-1795: The Spread of Settlement. (Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1983), pp191-192

[9] Bruce Swanton, A Chronological Account of Crime, Public Order & Police in Sydney 1788-1810. (Phillip: Australian Institute of Criminology, 1983), p12

[10] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony of New South Wales. (1798; repr., Adelaide: Libraries Board of South Australia, 1971), p284

[11] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony of New South Wales. (1798; repr., Adelaide: Libraries Board of South Australia, 1971), p284.

[12] John Cobley, Sydney Cove, 1793-1795: The Spread of Settlement. (Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1983), p29. Other lawbreakers included a man who had absconded from the hospital in February and had reappeared in Toongabbie where he was caught ‘stealing Indian corn’. A much more violent crime, the stabbing in the abdomen of Richard Sutton by Abraham Gordon, was also recorded, as was the self-inflicted injury of a soldier at Parramatta who had been sentenced to three hundred lashes and ‘sought to avoid this punishment by cutting his throat’ the same soldier then made a false confession, in relation to the murder of the missing watchmen, in another attempt to avoid the lash.

[13] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony of New South Wales. (1798; repr., Adelaide: Libraries Board of South Australia, 1971), pp335-36

[14] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony of New South Wales. (1798; repr., Adelaide: Libraries Board of South Australia, 1971), p336

[15] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony of New South Wales. (1798; repr., Adelaide: Libraries Board of South Australia, 1971), pp335-336

[16] John Cobley, Sydney Cove, 1793-1795: The Spread of Settlement. (Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1983),p102

[17] Richard Atkins, Journal, 1791-1810, National Library of Australia (Call No.: MS 4039), p47

[18] John Cobley, Sydney Cove, 1793-1795: The Spread of Settlement. (Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1983),p102

[19] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony of New South Wales. (1798; repr., Adelaide: Libraries Board of South Australia, 1971), p336

[20] New South Wales Police Force, website: History of the NSW Police Force – Significant Dates – 1788-1888 n.d., http://www.police.nsw.gov.au/about_us/history viewed 1 January 2016

[21] Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Joseph Looker and Ann Chapman 1797 Marriages. (Sydney: Justice, New South Wales Government, n.d.)

[22] Murder [Joseph Luker], The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser 28 August 1803 p4 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/625757 viewed 30 September 2018

[23] Louise Steding, Death on Night Watch: Constable Joseph Looker, 1803 (Sydney: In Focus, 2016), p16

[24] Sydney, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser 2 October 1803 p2 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/625802 viewed 30 September 2018

[25] Sydney, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser 2 October 1803 p2 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/625802 viewed 30 September 2018

[26] Rachel Franks, 'Writing the Death of Joseph Luker: True Crime Reportage in Colonial Sydney', TEXT: Journal of Writing and Writing Courses: Special Issue – Writing Death and Dying, 2017 45, p7,http://www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/issue45/Franks.pdf viewed 9 September 2018

[27] Rachel Franks, 'Writing the Death of Joseph Luker: True Crime Reportage in Colonial Sydney', TEXT: Journal of Writing and Writing Courses: Special Issue – Writing Death and Dying, 2017 45, p7,http://www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/issue45/Franks.pdf viewed 9 September 2018

[28] Louise Steding, Death on Night Watch: Constable Joseph Looker, 1803. (Sydney: In Focus, 2016), p4

[29] Paul B. Kidd, Australia’s Serial Killers: The Definitive History of Serial Multicide in Australia. (2000; repr.,Sydney: Pan Macmillan, 2006), pp1-8

[30] Rachael Weaver, The Criminal of the Century. (North Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing, 2006)

[31] Robert Travers, Murder in the Blue Mountains: Being the True Story of Frank Butler One of Australia’s Most Notorious Criminals. (Richmond: Hutchinson Australia, 1972)

[32] 'The Mutilator: Sydney Serial Killer William Macdonald Dies as NSW’s Oldest, Longest-Serving Prisoner', ABC News 14 May 2015, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-05-13/the-mutilator-sydney-serial-killerwilliam-macdonald-dies/6467626 viewed 9 September 2018

[33] Convict Records, John Lewis, Convict Records of the Home Office. (Brisbane: An Online Project of the State Library of Queensland, n.d.), http://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=slq_alma21132530280002061&context=L&vid=SLQ&search_scope=FHCOMBINED&tab=fhcombined&lang=en_US viewed 21 July 2019; Convict Records, Joseph Lucar, Convict Records of the Home Office. (Brisbane: An Online Project of the State Library of Queensland, n.d.), http://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au/primoexplore/fulldisplay?docid=slq_alma21116233100002061&context=L&vid=SLQ&search_scope=FHCOMBINE D&tab=fhcombined&lang=en_US viewed 10 September 2018; Sentenced Beyond the Seas: Australia’s Early Convict Records. (Sydney: State Archives & Records, New South Wales, n.d.), https://www.records.nsw.gov.au/archives/collections-and-research/guides-and-indexes/sentencedbeyond-the-seas-australias-early viewed 21 July 2019