The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Sydney's Metropolitan Goods Lines

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The Metropolitan Goods Lines, which spread throughout the Sydney suburbs from 1916 onwards, have played a key role in the industrialization of the city and the development of many suburbs. While some of these lines have become disused, others have been repurposed as light rail for the contemporary city.

The reason for the lines

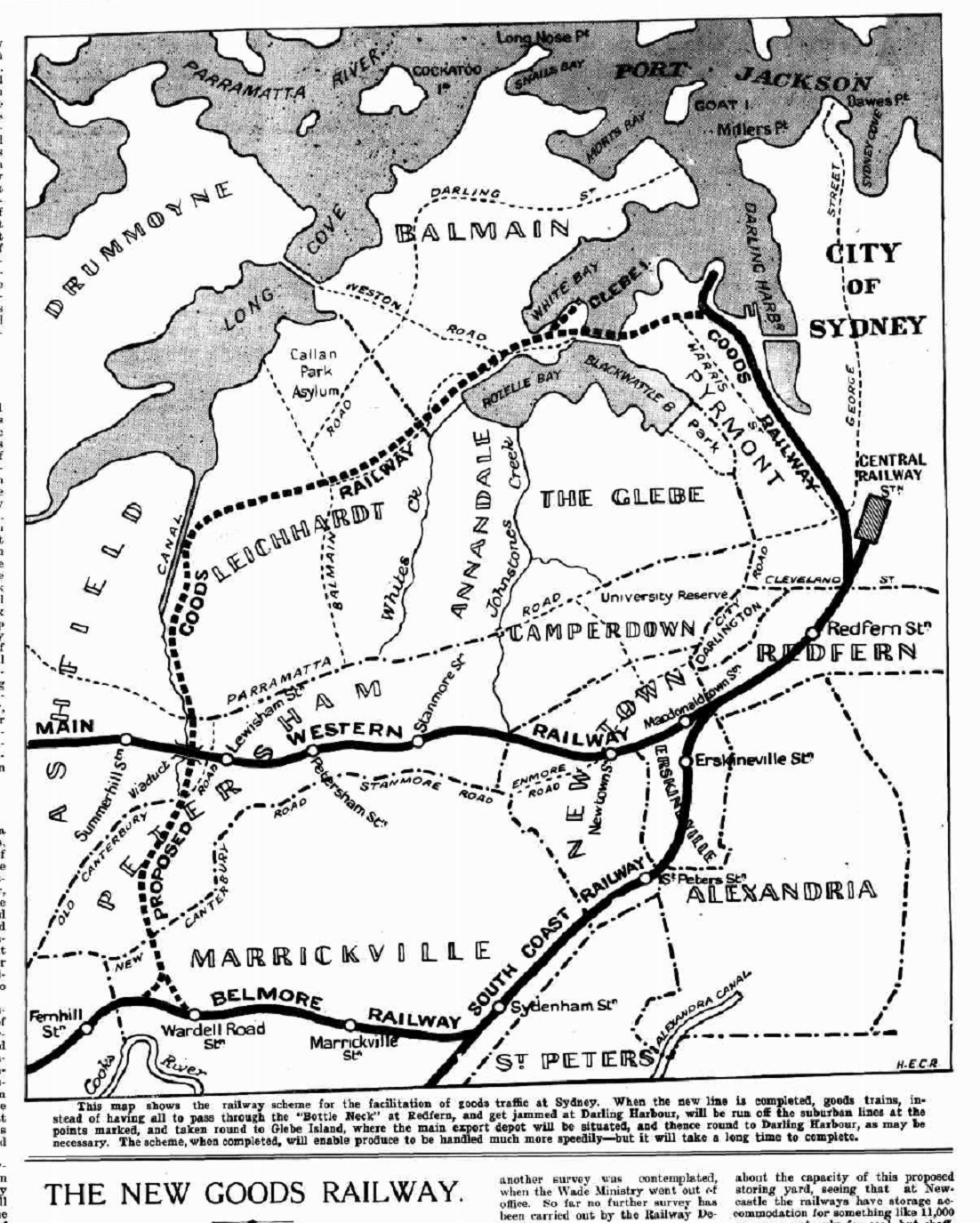

[media]Because the colonial politics of New South Wales were dominated by rural interests Sydney's railways were initially planned as trunk lines serving the rural hinterland. They provided cheap and efficient transport of rural produce to the city and its port, carrying manufactured goods to rural settlements, and fast, inexpensive transport for people.

After the end of the Federation drought of 1895–1903, there was rapid expansion of grain crops in the 'Wheat Belt' of the inland New South Wales. The area cropped grew from 426,976 acres (172791.057 hectares) in 1870–71 to 2,717,085 acres (1099565.288 hectares) in 1908–09. Transporting this grain, together with the increasing wool clip from the hinterland to the congested conditions at Darling Harbour posed a major challenge to the New South Wales Railway Commissioners who had to deal with the delays caused to suburban passenger trains by slow-moving goods trains on congested city lines.[1]

Railway Commissioner T R Johnson

Following a period of turmoil and conflict within the ranks of New South Wales railway commissioners, the government appointed a select committee in London to identify a suitable candidate for the position of Chief Commissioner of the New South Wales Railways. They unanimously appointed Thomas Richard Johnson, the assistant engineer of the Great Northern Railway in Britain, who was then aged 49. Mr Johnson arrived in Adelaide on the RMS Oroya on 1 April 1907 and reached Sydney on the Melbourne express train on 7 April.[2]

A priority for the new commissioner was rebuilding the capacity of the railways to keep pace with the demands of the booming rural economy. New capital works in 1908–09 included 470 miles of track rehabilitation or renewal, track duplication and crossing works, upgrading signalling interlocking at 39 locations and new tunnelling works to bypass the Lithgow Zig Zag. The department purchased an additional 97 locomotives, 104 passenger vehicles and 1064 freight vehicles.[3]

The design and construction of the Metropolitan Goods Lines were shaped by two reports by the Department of Public Works – the first released in July 1910, followed by a second report in November 1914 which focused on deviations between Rozelle and Pyrmont.[4]

The Metropolitan Goods Lines network was designed to address four issues:

1) Relieve pressure on the crowded wharves, transit sheds and goods yard at Darling Harbour by developing Glebe Island as an alternative; constructing a double-track from the Main Suburban Line at Summer Hill to White Bay, Rozelle and Darling Harbour together with and extension of this line to Wardell Road; provision of a large yard at Rozelle for goods wagons; building a grand wheat receiving and loading terminal, and two coal-loading berths at Glebe Island.

2) Relocate goods trains from crowded suburban lines by establishing the Metropolitan Goods Lines network (including the two lines noted above);

3) Connect the new State Abattoirs at Homebush with a new central meat market and offal treatment plants at Botany. A central meat market at Rozelle with dressing and chilling rooms, together with dedicated sidings, was planned, but did not proceed. Instead decentralised meat markets opened at Rockdale and St Leonards in April 1921. The location of offal treatment works at Botany meant that the goods line network would need to include a route from the State Abattoirs via Campsie to Botany.

4) Enable goods trains from the Illawarra to traverse the North, South and West lines. James Fraser, the Chief Commissioner between 1917 and 1929, argued for dedicated goods lines that facilitated stock trains using these lines. [5]

The Sydney Yard to Darling Harbour component of the Metropolitan Goods Lines had been built for the opening of the Sydney to Parramatta line in September 1855. The rest was new work. The Flemington to Belmore and Wardell Road to Glebe Island and Darling Harbour Railways Act (No 17) 1910 received assent on 12 August 1910. Land resumptions commenced the following year, while earth works, cuttings, embankments and bridges were proceeding satisfactorily by the middle of 1913.

On 23 June 1914, the new Chief Commissioner John Harper announced four additions to the project:

1) Quadrupling the Belmore to Wardell Road line, due to increased traffic on the Bankstown Line following its extension to Liverpool;

2) Constructing a 'great' marshalling yard at Enfield, which would become the nucleus of the goods line network;

3) Moving Eveleigh Workshops to Chullora (a proposal that did not eventuate); and

4) Deviating the authorised line between Rozelle and Darling Harbour. This was in response to requests from the Harbour Trust which was planning a massive expansion of wharves in the area. The new line would diverge near Rozelle Goods Yard and pass around Rozelle Bay before entering a four-track 178ft tunnel from which it joined the original route near Johnson Street. [6]

Opening the lines

Premier Holman and the Minister for Mines and Labour and Industry, Henry C Hoyle, accompanied then Assistant-Commissioner James Fraser, on an inspection tour of the line in late March 1916. They observed the new marshalling yards and locomotive depot at Enfield and the cleaning of livestock wagons and hot water washing sidings for the meat wagons at the State Abattoirs. They also inspected sidings for local goods traffic at Dulwich Hill, Leichhardt and Rozelle, reception sidings at Rozelle for Glebe Island and Darling Harbour, the bulk wheat loading wharves at Glebe Island, and construction work on the new goods line from Rozelle to Darling Harbour.[7]

The Belmore to Flemington section of the Metropolitan Goods Line opened on 11 April 1916. The Wardell Road–Rozelle and Glebe Island section on 29 May 1916. The delayed section from Rozelle to Darling Island opened on 23 January 1922 and the short main line to Darling Harbour the following August.

[media]The new marshalling yard and locomotive roundhouses at Enfield was a major infrastructure project. Its gravitation yard, with capacity for 4000 wagons, followed 'best practice' in North America and England. It featured 26½ miles (42.65 kilometres) of sidings. The new facilities for servicing and maintaining locomotives were subsequently upgraded to handle the huge 4-8-2 three-cylinder D57 Class goods locomotives introduced between 1930 and 1932.[8]

An early addition to the goods network was the Abattoirs Line, which left the Main Western Line at Pippita, crossing Parramatta Road on an overbridge and then serving the State Abattoirs via various meat sidings. The line opened on 31 July 1911 and the complex itself commenced operation on 7 April 1915.[9] In 1968 the Homebush Saleyards were relocated to the Abattoirs precinct, being accessed by a balloon loop of the Abattoirs Line. Sydney's fruit and vegetable markets were relocated from Haymarket to the old saleyard site adjacent to the Main Western Line in 1975. For many years, trains from the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area arrived at the market sidings each morning to unload fresh fruit and vegetables for sale at the markets.

Shaping Sydney's industries

Goods sidings at centres along the Metropolitan Goods Lines played an important role in the industrialization of a number of Sydney's inner suburbs. Notable examples were Dulwich Hill, which had two loop sidings and a goods shed; Charles Street in Leichhardt with one loop siding and goods shed; and Gordon Street, Rozelle which comprised a large loop on the western side of the marshalling yard. Road transport brought about their demise and they saw little use after 1970.

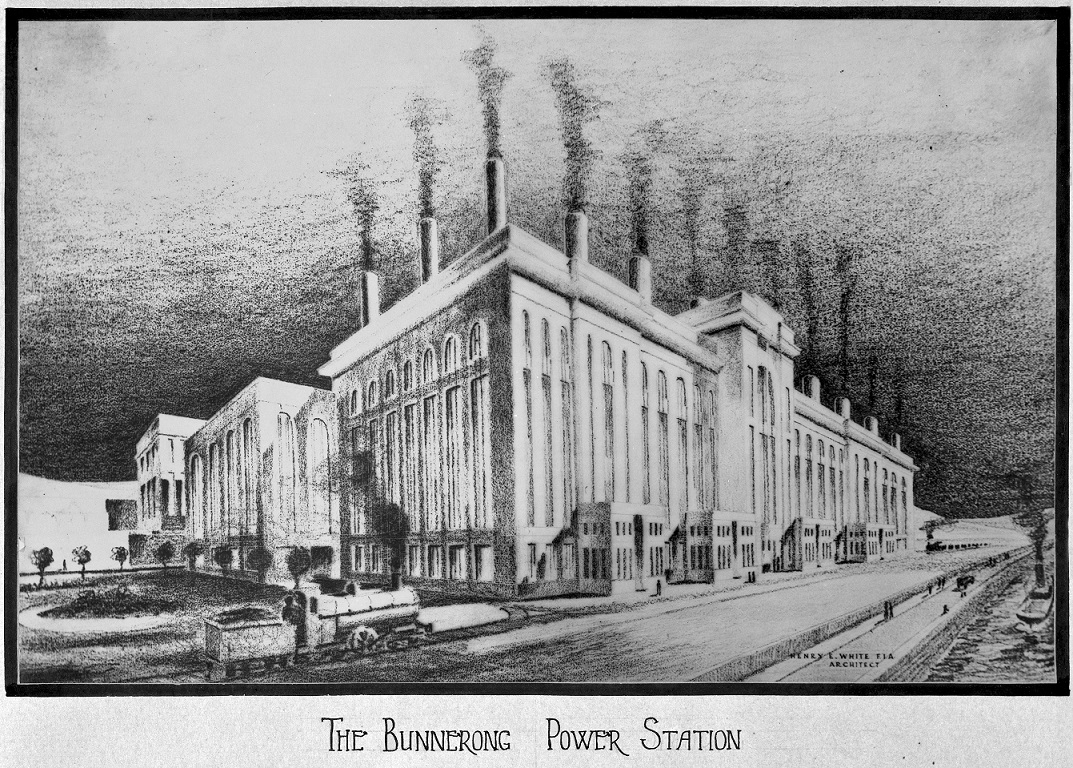

[media]Coal-fired power stations at Ultimo, Pyrmont and White Bay in the Darling Harbour–Rozelle area required large quantities of coal to fire the generators, as did the larger Bunnerong Power A and B Power Stations at Matraville. The latter involved an extension of the Goods Line from Botany to the power stations which the Sydney Municipal Council constructed and opened in 1929. The coal for these stations was transported over the Metropolitan Goods Lines from the Western coalfields and the mine at Glenlee south of Sydney. The Bunnerong power stations were decommissioned by 1975, although peak load gas turbines were in use on the site between 1982 and 1984.

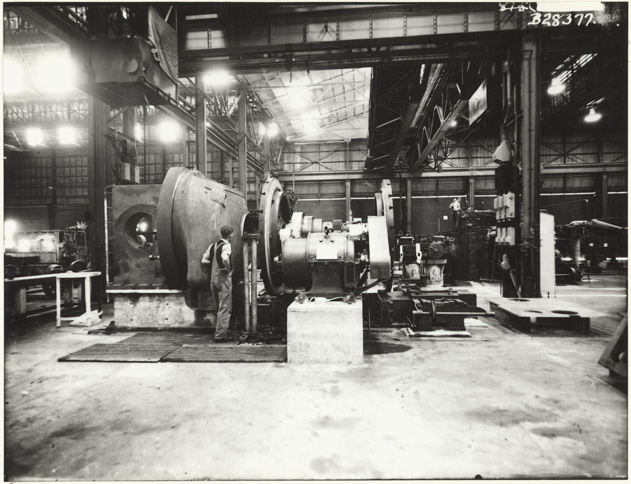

[media]The NSW Railways also had significant industrial enterprises associated with the goods lines. The locomotive depot at Enfield had significant workshops to maintain and repair the steam locomotives based there and with the introduction of diesel and electric locomotives in the 1950s, a new complex for their maintenance, the Diesel and Electric (DELEC) locomotive depot and maintenance centre, was established on the opposite side of the marshalling yard.

[media]A more significant workshop complex is the Chullora Railway Workshops. Its first three workshops opened in 1926 on 200 hectares of land adjacent to the Enfield marshalling yards. In its heyday it had ten individual specialist workshops undertaking work for three specialist branches of the NSW Railways, while during World War II it served as a major manufacturing and assembling plant for aircraft and tanks.[10] The Sydney Rail Freight Terminal opened on the site in October 1984, while the ELCAR workshop that maintained suburban electric trains was closed in March 1994, with maintenance of the City Rail fleet being taken over by A Goninan and Company at its new Auburn facility. By 2017, many of the workshops had closed and their work is undertaken by new privately-operated facilities elsewhere.

Flour mills located on the Goods Lines provided a regular source of rail traffic, such as the Mungo Scott mill north of Dulwich Hill on the line to Rozelle and the Edwin Davey flour mill at Darling Harbour. The Rozelle–Darling Harbour section closed in January 1996 and Rozelle Yard closed on 17 January 2009. The last train ran to the Mungo Scott flour mill on 1 December 2008. The Rozelle Bay wharves served Crest flour mills and the Clyde Sawmilling complex. On the Botany Line, the Kellogg's plant at Gelco was a major industry served by goods trains which delivered grain to its towering silos.

Changing technology

The safe operation of trains depends on the effectiveness of the signalling system and the vigilance of the crews operating the trains of the rail network. At the time of opening the Metropolitan Goods Lines had different signalling systems on various sections of line, including Track Circuit Block, Tyers Three Wire Block and automatic signalling, with the latter limited to the Enfield South to Canterbury and Canterbury to Wardell Road sections. Track Circuit Block working was a cheap expedient, which used track circuits but there were no intermediate signals between signal boxes while the Tyers block sections had temporary mechanical signals.[11]

The goods line from Sydney Yard to Darling Harbour was electrified and commissioned on 1 October 1959. The manual block signalling sections were replaced by automatic signalling in August 1974 following the 1965 electrification of the lines between Canterbury and Rozelle. Electrification of this section of the goods lines was undertaken to facilitate the use of electric locomotives on coal trains travelling from Glenlee and/or Campbelltown to Rozelle.[12]

The transition to diesel-electric and electric locomotives for freight train working from the 1950s resulted in much longer freight trains coming into and departing from Sydney on the main lines. By the 1990s, providing paths for these trains amid increasing suburban passenger train traffic had become a challenge. On 21 April 1995, a bottleneck between Homebush and Flemington Goods Junction was removed with the opening of a single-track goods line which had an underpass under the Short North Line enabling freight trains to access the Homebush loop unimpeded.

The other major change was containerisation. Initially container ship berths were established at Balmain, but this was recognised as a temporary measure. The Maritime Services Board pushed for a container facility at Port Botany and, with government endorsement, work commenced on construction of two container terminals adjacent to Sydney Airport in 1972. Premier Neville Wran officially opened the northernmost one as Brotherson Dock in 1979, with the second, Brotherson Dock Two, opening in October 1982. The Public Transport Commission commenced upgrading and extending the Botany Line to access the Port Botany container terminals in 1977. In the interim, containers were railed to a terminal at Botany and then road-hauled to the container docks. The initial plan was to duplicate, extend and electrify the line to the Port Botany terminals, in order to transport 12 million tonnes of coal to the port in addition to containers, but local opposition to coal export through Port Botany resulted in a more modest upgrade with passing loops and 2.2km of new track. The outcome inhibited rail's capacity to carry containers to and from Port Botany, which is currently being addressed.[13]

More significant was the Southern Sydney Freight Line, a $1 billion 36-kilometre single track line built by the Australian Rail Track Corporation for freight trains on the Main South Line to use a dedicated line from south of Macarthur to Enfield West. On the Main Northern Line the Northern Sydney Freight Corridor provided a dedicated underpass to North Strathfield for freight trains to pass under the western suburban passenger lines, together with dedicated freight lines bypassing passenger stations on the Main Northern Line.

Much of the Metropolitan Goods Line network remains in place, but the original section from Sydney Yard to Darling Harbour, together with later extension to Wentworth Park, was converted to Sydney's first passenger carrying modern light rail line, which opened in August 1997. The section from Central Station to the former Haymarket complex followed a former tram route and then utilised the former Goods Line right-of-way. The line was extended to Lilyfield in August 2000 and the link to the Main Suburban passenger line at Dulwich Hill formally opened on 27 March 2014.[14]

References

Pollard, Neville. 'City Meets Country: Centenary of the Metropolitan Goods Lines.' Australian Railway History No 242, April 2016.

Pollard, Neville. 'The Story of the Abattoirs Line.' ARHS Bulletin 36 (571–2, May and June 1985).

NSW Office of Environment & Heritage. State Heritage Register. Chullora Railway Workshops, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=4801108.

Harper, Graham. 'Thoughts of Sydney Metro Goods Line Signalling.' Australian Railway History, No 948 (October 2016).

McKillop, Bob. 'Australian Railways and the Container Revolution Part 3: Linking with the World. 'Australian Railway History. No 911 (September 2013).

Railway Digest (May 2014).

[1] Neville Pollard, 'City Meets Country: Centenary of the Metropolitan Goods Lines', Australian Railway History, No 242, April 2016, 15–9

[2] The New Chief Commissioner, Australian Town and Country Journal, 30 January 1907, 16; Chief Railway Commissioner, Sydney Morning Herald, Thursday 7 April 1907, 6

[3] Neville Pollard, 'City Meets Country: Centenary of the Metropolitan Goods Lines', Australian Railway History, No 242, April 2016, 16

[4] A GOODS RAILWAY. The Daily Telegraph. 29 July 1910, 4; Deviation of Authorised Goods Railway Line to Darling Island, as between the head of Rozelle Bay and Pyrmont, Reports of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works regarding Railways 1914; Neville Pollard, 'City Meets Country: Centenary of the Metropolitan Goods Lines', Australian Railway History, No 242, April 2016, 16

[5] Neville Pollard, 'City Meets Country: Centenary of the Metropolitan Goods Lines', Australian Railway History, No 242, April 2016, 18–19

[6] NSW Office of Environment & Heritage website, State Heritage Register, Chullora Railway Workshops https://web.archive.org/web/20171204050046/http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=4801108, viewed 27 August 2017

[7] Graham Harper, 'Thoughts of Sydney Metro Goods Line Signalling', Australian Railway History, No 948, October 2016, 18

[8] Bob McKillop, ‘Australian Railways and the Container Revolution Part 3: Linking with the World’, Australian Railway History, No 911, September 2013, p9.

[9] Neville Pollard, 'The Story of the Abattoirs Line', ARHS Bulletin, Vol 36, 571–2, May and June 1985.

[10] NSW Office of Environment & Heritage website, State Heritage Register, Chullora Railway Workshops, https://web.archive.org/web/20171204050046/http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=4801108, viewed 27 August 2017

[11] Graham Harper, 'Thoughts of Sydney Metro Goods Line Signalling', Australian Railway History, No 948, October 2016, 13

[12] Graham Harper, 'Thoughts of Sydney Metro Goods Line Signalling', Australian Railway History, No 948, October 2016, 18

[13] Bob McKillop, 'Australian Railways and the Container Revolution Part 3: Linking with the World', Australian Railway History, No 911, September 2013, 9

[14] Railway Digest, May 2014, 36