The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

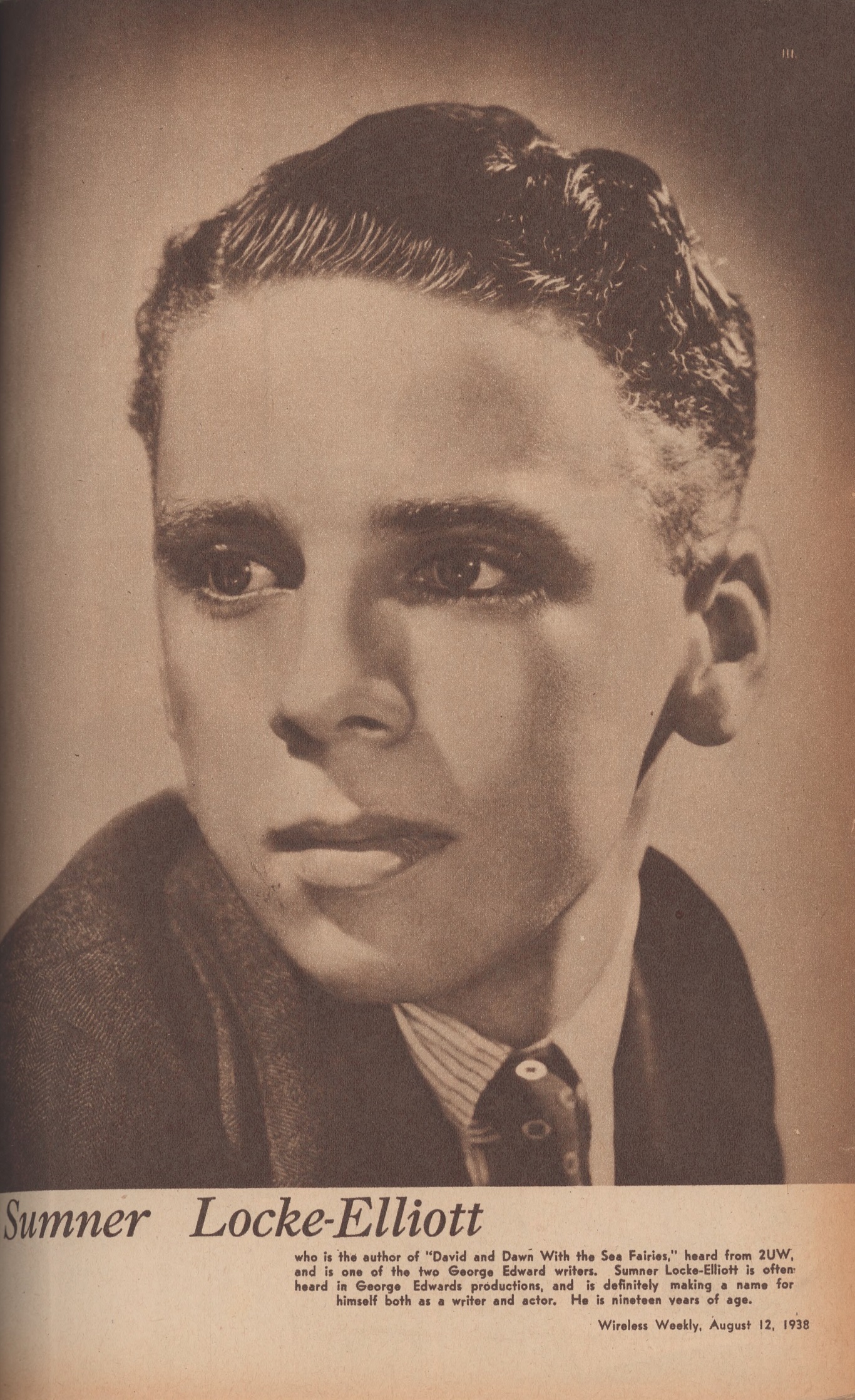

Sumner Locke Elliott

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Sumner Locke Elliott, actor, playwright and novelist, lived in Sydney until 1948 and thereafter in the United States. [media]In the 1960s after a successful career as a playwright he decided to reinvent himself as a novelist and of his ten novels five are based on his life in Sydney between the 1920s and 1940s. He won the Miles Franklin Award in 1963 and the Patrick White Award in 1977. White, Australia's only Literature Nobelist, and a man not bereft of ego, once said that Elliott was the finest living Australian novelist, apart from himself of course.[1]

Birth and Childhood

In December 1916 writer Helena Sumner Locke married clerk and freelance journalist Henry Logan Elliott, then serving with the Australian Army. A few weeks later Henry was transferred overseas. On 18 October 1917 Helena died the day after giving birth to a boy at The Laurels Private Hospital, Kogarah, but not before naming him, somewhat curiously, after herself.[2] Henry, then in England, arranged for the baby to be cared for by two of his wife’s sisters. Unfortunately the sisters often disagreed about what would be best for the child, causing him to be moved back and forth between them and from school to school. In 1927, when he was ten, a court ordered he be sent to the private Cranbrook School as a boarder in order to resolve a disagreement about where he should live.[3] These disputes only came to an end with the death of one of the sisters when he was twelve.

His childhood was therefore stressful and difficult, his schooling was frequently interrupted and he had few opportunities to make lasting friendships with his peers. His first novel in particular, Careful, He Might Hear You (1963), is based on his turbulent and traumatic early years.

Actor and Playwright

Although he hated his two years at Cranbrook, in retrospect they set him up for a life in the theatre and as a writer. An English teacher at the school encouraged him in acting and arranged an audition for a part in a radio play. This led to a successful twenty years or so both acting in and writing for radio serials in Sydney for the George Edwards Players on station 2UW and elsewhere. He also joined the Junior Theatre League as a teenager and in 1933 won a prize for his production of his own play Storm.[4]

He left Neutral Bay Intermediate High School at sixteen and secured an office job with the JC Williamson organisation. At that time Doris Fitton’s Independent Theatre group had rooms at King Street in the city above the Mary Elizabeth Tea Room and Gypsy Palm Readings.[5] He frequently spent his lunch periods there meeting actors and discussing plays and their production. He joined the Independent’s acting group and wrote a number of plays which Fitton produced and directed. During his teens and twenties he called himself Sumner Locke-Elliott which he thought sounded more sophisticated; in later life he admitted that he had been ‘terribly conceited’ as a young man.[6] [media]His radio work with George Edwards led to live performances on the ABC, 2GB, 2SM and other stations. As well as acting he was also writing serials for Edwards and other radio companies, often at great speed in order to keep up with the relentless demand for copy. Although this heavy workload produced a good income and taught him valuable lessons about writing and plot development he later referred to this period as ‘potboiling’ to produce ‘dramatic sludge’.[7]

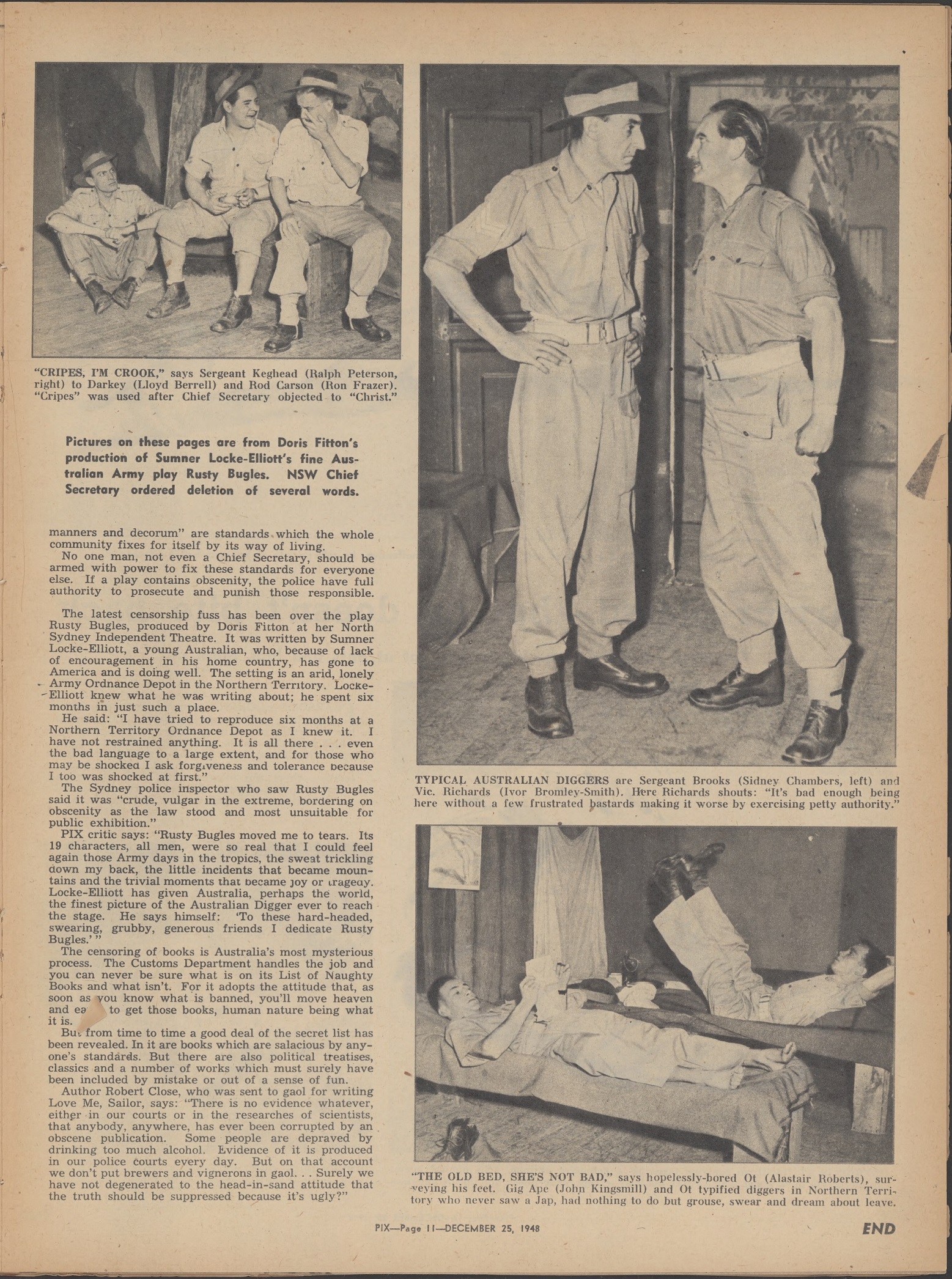

[media]This hectic but very enjoyable career ended when he was called up for service in World War II and spent four boring years as a clerk in army posts in various parts of Australia. After the war he turned these experiences into a stage play Rusty Bugles (1948). Police action over its raw barracks language ensured wide public interest and eventually forced a revision of Australian censorship laws.[8]

Emigration to USA

The glamour of Hollywood and its films had long fascinated Elliott and in 1938 he had applied to emigrate to the United States. War intervened but permission was granted in 1948 and he seized the opportunity. His interest in America had been intensified by an affair with a American officer in Sydney after the war. Although he loved acting he soon realised that his abilities were comparatively modest so he turned to writing for the theatre rather than acting in it. At that time television networks broadcast much live drama and he became very successful as a television playwright. He became an American citizen in 1955.

Novelist

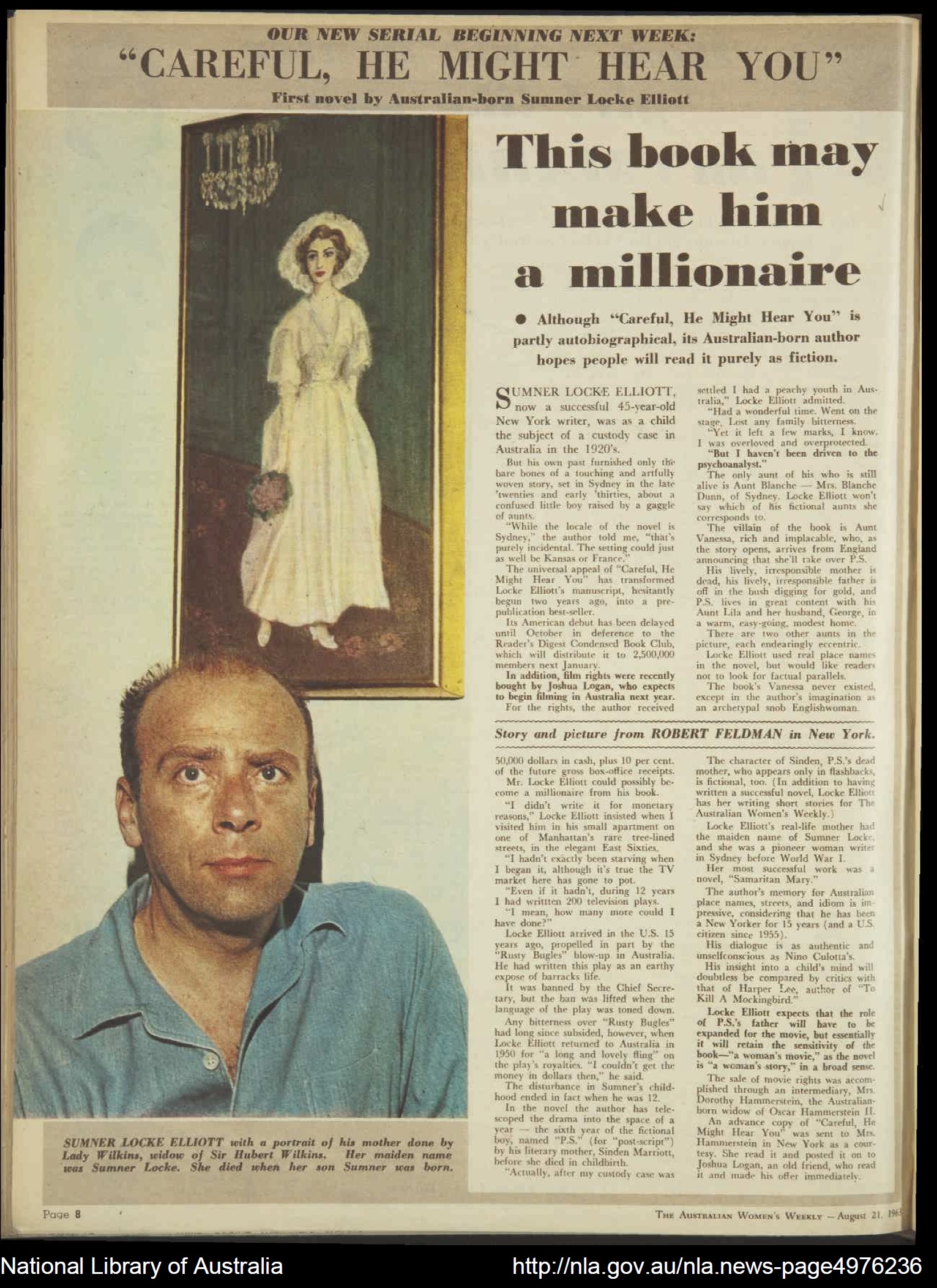

[media]Elliott left television writing in 1962 to write a novel, published in 1963 as Careful He Might Hear You.[9] His biographer Sharon Clarke says that in his novels 'the boundary between fact and fiction is not only blurred, it is almost invisible’.[10] Certainly they illustrate Alberto Moravia's aphorism that fiction is a higher form of autobiography. Most are set in Sydney between World Wars I and II and deal with a child or young man struggling to come to terms with life in the confusing context of a dysfunctional family. His real family members and their interactions with him are important presences in most of his works, as are loneliness, repressed emotions and desires, and the bewildering difficulty of trying to discover oneself in the absence of normal family relationships.

Although Elliott never returned to live in Australia, it was Sydney that he wrote about from his New York home. As well as the iconic places like Manly and Bondi beaches, Centennial Park and the Botanic Gardens, he remembered and wrote of Gowing’s menswear shop, the Marble Bar at the Hotel Australia, Sargent’s meat pies, travelling on harbour ferries, Wynyard station, the Fairyland picnic grounds on the Lane Cove River at Ryde and the speakers in the Domain, to give only a few examples. He often used as settings the suburbs where he had lived with his aunts – Hurstville, Rockdale, Bexley, Vaucluse, Cremorne, North Sydney and Neutral Bay. Given his theatrical background it is not surprising that some of Sydney’s more bohemian haunts are featured such as Kings Cross, Rowe Street and its little cafes, and the theatres he frequented as actor or spectator – the Independent, Tivoli and Minerva for example. Life in Sydney during the 1920s to 1940s is vividly captured, perhaps no better than in his frankly autobiographical novel Fairyland (1990) which Dennis Altman described as “the most revealing documentation we have of homosexual life in Sydney in the 1930s and 40s.”[11]

Sydney then was a very different place from the one we know but Elliott’s characters and settings bring it back to life. ‘I still see the Sydney of 1937 in my mind’s eye ... the trams in George Street, I know they are all gone – but that’s my city of Sydney, locked like a fly in amber ...’.[12]

References

Sharon Clarke, Sumner Locke Elliott, Writing Life, Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1996

Jill Roe, 'Elliott, Sumner Locke (1917–1991)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/elliott-sumner-locke-14903/text26094, published online 2014, viewed 27 September 2018.

Neil Radford, 'Elliott, Summner Locke (1917-1991)', Robert Aldrich, Garry Wotherspoon (eds), Who's Who in Contemporary Gay and Lesbian History Vol.2: From World War II to the Present Day, London: Routledge, 2001.

Notes

[1] Sharon Clarke, Sumner Locke Elliott, Writing Life, Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1996, ix

[2] DEATH OF SUMNER LOCKE, Sydney Morning Herald, 10 October 1917, 8 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15736275; AUSTRALIAN WRITER'S DEATH, The Sun, 21 October 1917, p4 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article221407541, viewed 27 September 2018

[3] WITH AUNTS, The Sun, 22 August 1927, 10 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article222484360; MOTHERLESS LITTLE "PUTTY", Truth, 21 August 1927, 17 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article168682731, viewed 27 September 2018

[4] JUNIOR THEATRE LEAGUE, The Daily Telegraph, 23 August 1933, 13. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article248121757; LITTLE THEATRES, Australian Women's Weekly, 17 June 1933, 33 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article51387189, viewed 27 September 2018

[5] Sharon Clarke, Sumner Locke Elliott, Writing Life, Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1996, 113

[6] Sharon Clarke Sumner Locke Elliott, Writing Life, Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1996, 82

[7] Sharon Clarke Sumner Locke Elliott, Writing Life, Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1996, 134

[8] Play 'Rusty Bugles' Is Banned, Sydney Morning Herald , 23 October 1948,1 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article18093381; SUN Readers Say, The Sun, 26 October 1948, 9 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article231143291; PLAYWRIGHT ATTACKS BAN Daily Telegraph, 26 October 1948, 5 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article248374483, viewed 27 September 2018

[9] This book may make him a millionaire, Australian Women's Weekly, 21 August 1963,8 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article52269028, viewed 27 September 2018

[10] Sharon Clarke Sumner Locke Elliott, Writing Life, Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1996, 278, 10

[11] Dennis Altman, 'Sumner Locke Elliott crushed by the sexual constraints of the pre-war world', The Australian, 6 April 2013 https://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/sumner-locke-elliott-crushed-by-the-sexual-constraints-of-the-pre-war-world/news-story/f22bbabb95a9692e78bd7d82353092a3?sv=2dde11b994c9018505867a445878d7e5 viewed 27 September 2018

[12] Sharon Clarke Sumner Locke Elliott, Writing Life, Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1996, 230