The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Stace, Arthur

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Stace, Arthur Malcolm

[media]Arthur Stace was born in Redfern in 1885, the fifth child of a labourer from Mauritius. His parents were alcoholics, and Arthur became a state ward at the age of 12. He received very little formal education and had already learnt to drink heavily by the time he started his first job at 14. His early years were spent in and out of jail and hospital, including a stay at Broughton Hall psychiatric clinic at Callan Park. He was briefly employed by the Sydney City Council, but mostly survived through underworld connections, working as a 'cockatoo' for various illegal establishments and delivering illicit grog to brothels, including one in Surry Hills run by his sister.

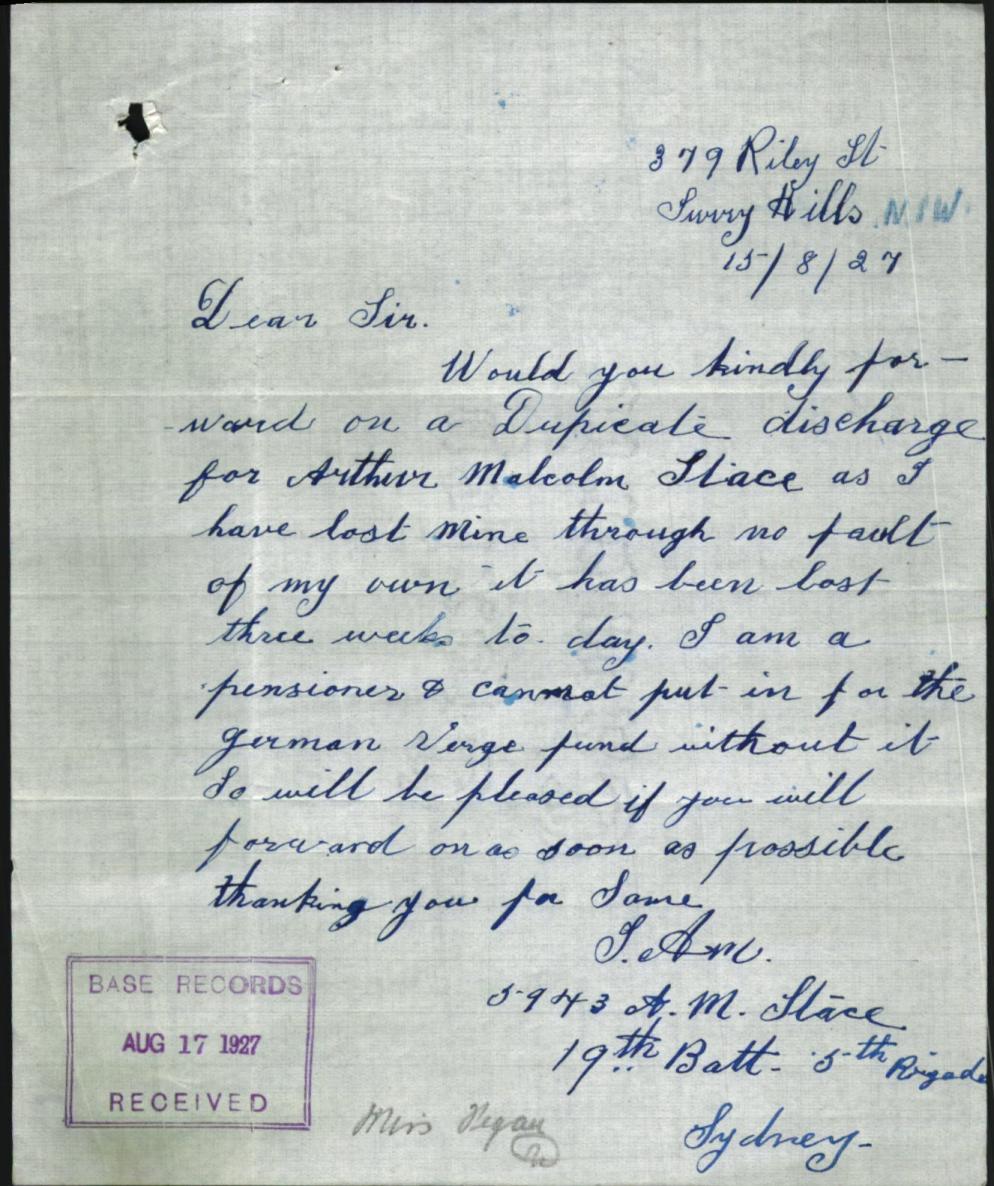

[media]He served in France with the 19th Battalion and returned home partially blind in one eye. Years of depression and drinking followed, with the bottle dominating his days and the courts regularly hauling him in for a variety of unacceptable behaviours.

Conversion

[media]Stace attended a 'tea and rock bun' meeting on 6 August 1930 at St Barnabas, Broadway, where Archdeacon RBS Hammond was attracting large hungry audiences of down and outs. Stace was, according to legend, unexpectedly converted to Christianity, and gave up the grog forthwith. Later, he was fond of saying 'I went in to get a cup of tea and a rock cake but I met the Rock of Ages'. His life changed direction completely, and he spent his spare hours in the following years visiting other afflicted souls and preaching on street corners, at William 'Cairo' Bradley's tent missions and to anyone who would listen. He led open air meetings on the corner of George and Bathurst streets for over 20 years.

He worked for a time at one of the self-help Hammond Hotels in a converted factory in Buckland Street Chippendale, where unemployed men were fed, shaved and spruced up in order to improve their chances of finding work. Later he was employed as a janitor at the Burton Street Baptist Tabernacle in Darlinghurst, where he joined the congregation. It was here that he heard a sermon delivered by the popular evangelist, John G Ridley in November 1932. Stace was enthralled when Ridley delivered the words,

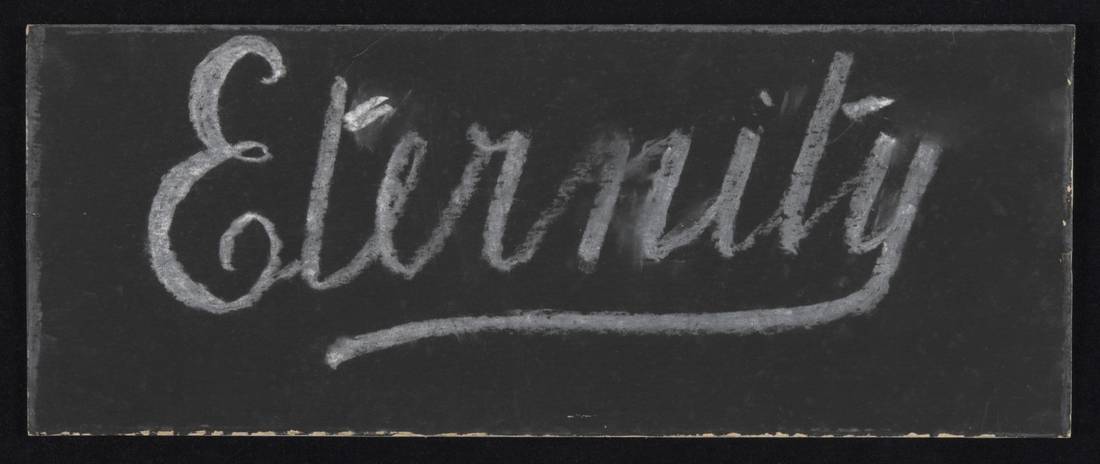

Eternity, Eternity, I wish I could sound or shout ETERNITY through the streets of Sydney ... You've got to meet it, where will you spend Eternity?

He left the service feeling 'a powerful call from the Lord', and discovering a piece of chalk in his pocket, believed he had found his purpose in life. He also claimed supernatural intervention.

The funny thing is that before I wrote it I could hardly have spelt my own name. I have no schooling and I couldn't have spelt Eternity for a hundred quid. But it came out smoothly in beautiful copperplate script. I couldn't understand it. [1]

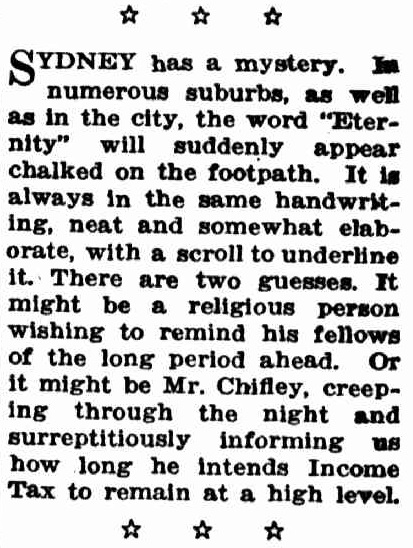

Mystery uncovered

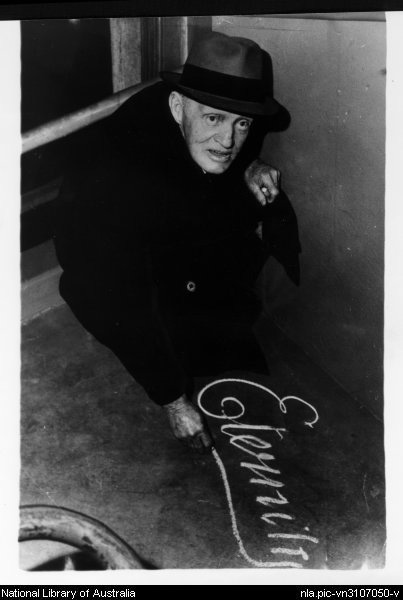

[media]Stace married in 1942 and lived with his wife Pearl for many years in Bulwara Road, Pyrmont. He chose to write the word in the hours before dawn when few people were around, keeping his identity a secret. Newspaper writers wrote speculative accounts and the occasional false confession helped to maintain the air of mystery that surrounded the anonymous Eternity man. Lisle Thompson, the minister of the Tabernacle eventually caught his janitor in the act. He wrote up the story in a short tract, and the Sunday Telegraph carried an article exposing the identity of the scribe on 21 June 1956.

Stace inscribed the word Eternity on Sydney's pavements more than half a million times between 1932 and 1966. In that year he went to live at the Hammondville Church of England aged people's home, where he died of a stroke on 30 July 1967. He donated his body to the University of Sydney and his remains were finally interred at the Botany Cemetery in 1969.

Stace's legacy

[media]The ghostly figure of this little man darting through the shadows to deliver his one word sermon has entered the mythology of Sydney's life. An early tract written by the Burton Street Baptist minister, Lisle Thompson has gone through various printings and is now available online. [2] A few years after his death, the poet Douglas Stewart wrote of 'that shy mysterious poet Arthur Stace, whose work was just one single mighty word'. Keith Dunstan included the story in his book Ratbags published in 1979. Artist George Gittoes incorporated a version of Stace's face in his Ancient Prayer, which won the Blake Prize for religious art in 1992 and Lawrence Johnston's film Eternity appeared in 1994. Stace's life continues to inform exhibitions and artworks and is often retold in religious tracts and sermons. Websites devoted to his story proliferate.

Jonathan Mills and Dorothy Porter's chamber opera, The Eternity Man was performed at the Sydney Festival in 2005. When Porter was asked why she thought Sydneysiders maintained such an 'enduring obsession' with Stace, she suggested that

Sydney is a waterside city, ephemeral, built from sandstone, itself almost dissolvable, unlike Melbourne's bluestone. And Sydney has a dreadful history of wiping out itself – in the 1960s especially, when everything got razed, covered over with concrete. We had a rather ruthless pro-development state government, there was corruption everywhere. So perhaps [Stace] appeals to us as a symbol of that past, that other lost Sydney and its history. [3]

Others refer to the unexpected spirituality of discovering his work juxtaposed against the hard-edged city. Artist Martin Sharp has helped to keep Stace centre stage through his own representations of the word Eternity. According to Sharp, Stace was

one of Sydney's most important writers, wasn't he? He never had a book published, but he self-published all over the streets and pavements of Sydney. He writes an entire novel in that word. [4]

References

Lisle M Thompson, 'The Crooked Made Straight', http://www.pastornet.net.au/stace/Power_1.htm viewed 4 October 2007

J G Ridley, The Passing of Mr Eternity, Sydney, 1967

Keith Dunstan, Ratbags, Golden Press, Sydney, 1979

Chris Cunneen, 'Stace, Arthur Malcolm (1885–1967)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 12, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1990, pp 42–43, http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A120052b.htm

Notes

[1] Tom Farrell, Sunday Telegraph, 21 June 1956

[2] http://www.pastornet.net.au/stace/Power_1.htm viewed 4 October 2007

[3] Sharon Verghis, 'One word sermon we can't forget', Sydney Morning Herald, 19 January 2005

[4] Sharon Verghis, 'One word sermon we can't forget', Sydney Morning Herald, 19 January 2005

.