The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Shark Arm murder 1935

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Shark Arm murder

[media]On 17 April 1935, a fisherman hooked a small shark off Coogee Beach. Then, a four-metre tiger shark swallowed the smaller shark, allowing it to be caught too. But instead of dumping his catch, the fisherman took the larger shark – still alive – to the nearby Coogee Aquarium Baths, where it would make a wonderful attraction for the following Anzac Day weekend.

At that time in Sydney, the shark was 'public enemy number one', since in late February and early March, three young men had been taken by sharks at New South Wales beaches. Bounty hunters were employed to help rid Sydney's beaches of the menace, so crowds now flocked to see this monster with man-eating capabilities, which was given the run of the pool.

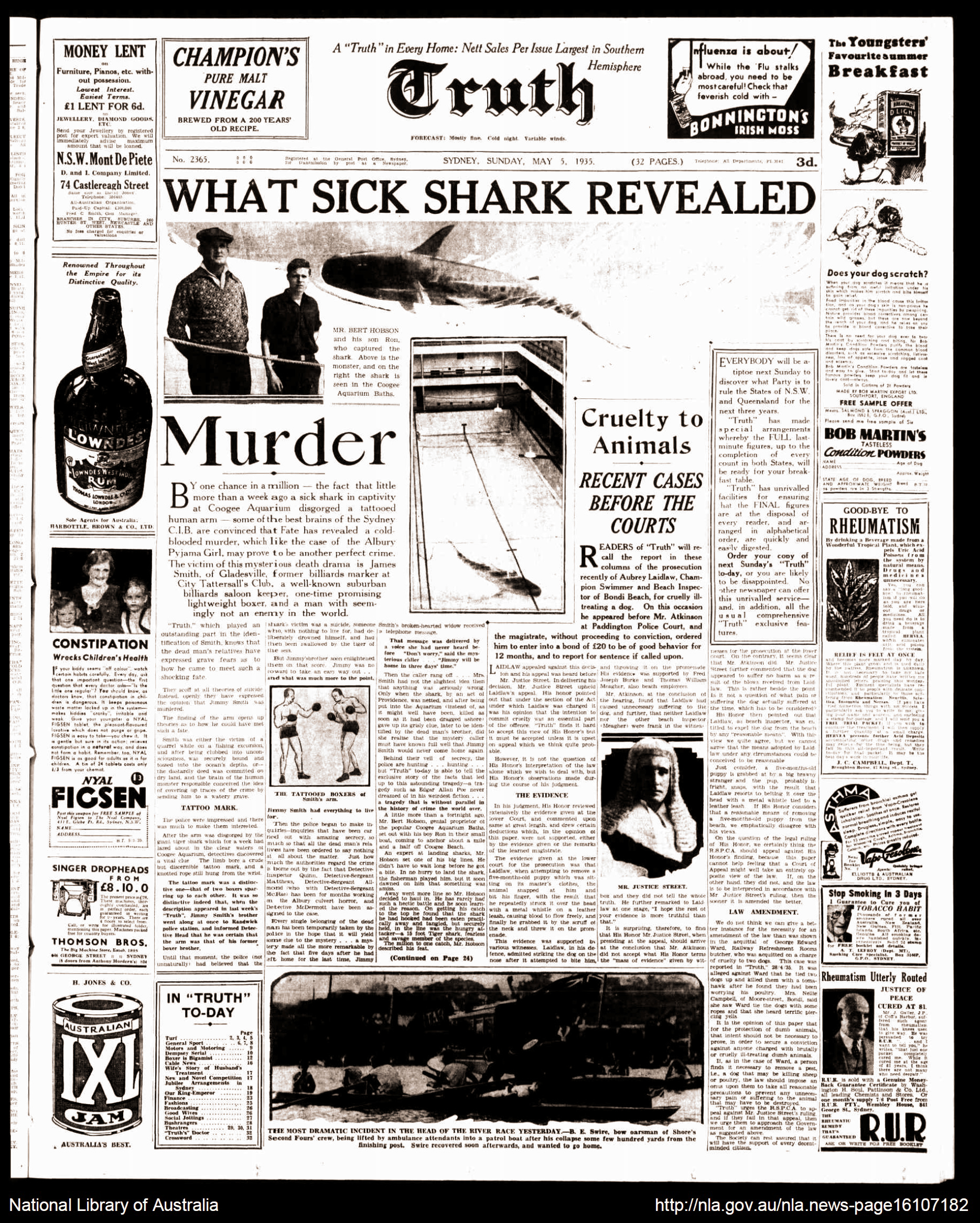

[media]For several days the shark seemed quite active and had a voracious appetite, but on 25 April, Anzac Day, it began acting strangely: it appeared ill, moved slowly and was seemingly disoriented. Then suddenly there was a great commotion in the pool, and while spectators watched, the shark vomited up a human arm.

The murder of Jim Smith

[media]At first, another tragic accident was presumed, but a medical examination of the arm revealed it had not been bitten off by the shark but had been removed from its body with a knife or other sharp instrument, and not in a surgical procedure. The focus of the investigation turned to murder. The gastric juices of sharks are highly acidic, but it was estimated that the arm could have been in its stomach for between eight and 18 days. Yet the arm was so well preserved that there was a still recognisable tattoo of two boxers shaping up to fight on the forearm.

After reading a report in a Sydney newspaper, Edwin Smith contacted police, suggesting that the arm could belong to his brother James, who had been missing for several weeks. And because of the well-preserved state of the arm, police managed to obtain some fingerprints, which confirmed that the arm had in fact belonged to Jim Smith.

Smith was a bankrupt builder, a former SP bookmaker and boxer, and a small-time criminal with a record of minor convictions, who had drifted onto the edges of the underworld and became involved in the illegal gambling that was rife throughout Sydney at that time.

Patrick Brady's taxi ride

[media]Police investigations found that Smith had last been seen drinking with his long-time friend, Patrick Brady, in the Cecil Hotel at Cronulla; they had then returned to a cottage rented by Brady on the shore of Gunnamatta Bay. Brady, who was also well known to the law, was an expert forger.

A key link for the police in their investigations was information they got from a Cronulla cab driver. On the morning after Jim Smith was seen for the last time, Brady hailed the cab in Cronulla and asked to be taken to North Sydney, where the cab was directed to pull up outside a house that turned out to be the home of middle-class businessman Reginald Lloyd Holmes.

Holmes was a seemingly respectable entrepreneur who ran a highly successful boatbuilding business on the harbour foreshore at McMahons Point on Lavender Bay. But Holmes was also known to be involved in other activities. He controlled a lucrative smuggling ring using speedboats built at his boatshed to pick up cocaine, cigarettes and other contraband thrown overboard from ships passing off Sydney Heads. Smith was a sometime employee of Holmes, and often drove one of the speedboats during the smuggling operations. But they had fallen out over a failed insurance scam, and it was speculated that Smith had begun to blackmail Holmes, using the boatbuilder's position in society as leverage. And Brady's taxi journey linked Jim Smith's murder directly to Holmes.

But all the evidence the police had collected so far against Brady and Holmes was purely circumstantial. They needed a confession. So police arrested Brady, and took him to Central Police Station. Holmes was also brought in, but he denied ever knowing Brady.

Suicide and speedboats

The case seemed stalled until 20 May, when Holmes left his boatshed in a very fast speedboat, sped out into the harbour, and, pulling out a pistol, attempted suicide. He failed, and fell into the water, but a rope got caught around one of his wrists as he fell, stopping him from drowning. The shock of the water revived him, and he crawled back aboard. The water police were alerted to these goings-on, and for four hours chased Holmes, out past Circular Quay, through the mid-morning ferry traffic, right down Sydney Harbour until, finally, he gave up just outside Sydney Heads.

Holmes was arrested and started to talk, agreeing to be a witness against Brady, whom police then charged with the murder of Smith. But at 1.20 am on 12 June, just hours before the start of the inquest into Smith's death, Holmes's body was found slumped over the wheel of his car, in the deserted docks area of Dawes Point.

With the death of Holmes, the Crown case against Brady for Smith’s murder collapsed. Although the cab driver testified that Brady had been dishevelled, had kept a hand in his pocket and wouldn't take it out, and was clearly frightened that somebody was following him, the trial was over in less than two days, and the judge directed that a verdict of not guilty should be reached. Brady was acquitted and walked from the court a free man.

Fixing the fizgig

But then more information began to come out. Smith had been a police informer – a 'fizzer', or 'fizgig' as they were called at the time – and had informed on a young man called Eddie Weyman. As a result of the information that Smith gave to the police, Weyman and one of his mates were caught red-handed raiding a bank. Though the crimes were never formally linked, the author Alex Castles has offered the opinion that Weyman was a likely suspect for the murder of Holmes.

Weyman was one of the most dangerous criminals in Sydney in the 1930s, a time when the underworld was populated by hard men and women who didn't hesitate to use violence to get what they wanted. Holmes was deeply involved in the lucrative but dangerous cocaine trade, and could well have been the victim of a gangland-style killing, as Sydney, in this period, was experiencing a crime wave. There was open gang warfare in the streets of Kings Cross and East Sydney, battles over control of cocaine distribution and prostitution: Darlinghurst was commonly known as Razorhurst, after the gangs' most used weapon. And there was one unwritten rule – never squeal to the cops. So with both Smith and Holmes, it could have been a case of 'cleaning up': getting rid of those who had fallen out with some of Sydney's leading criminals.

Brady, who was a World War I veteran, died in Concord Hospital in 1965.

References

Alex Castles, The shark arm murders, Wakefield Press, Kent Town SA, c1995

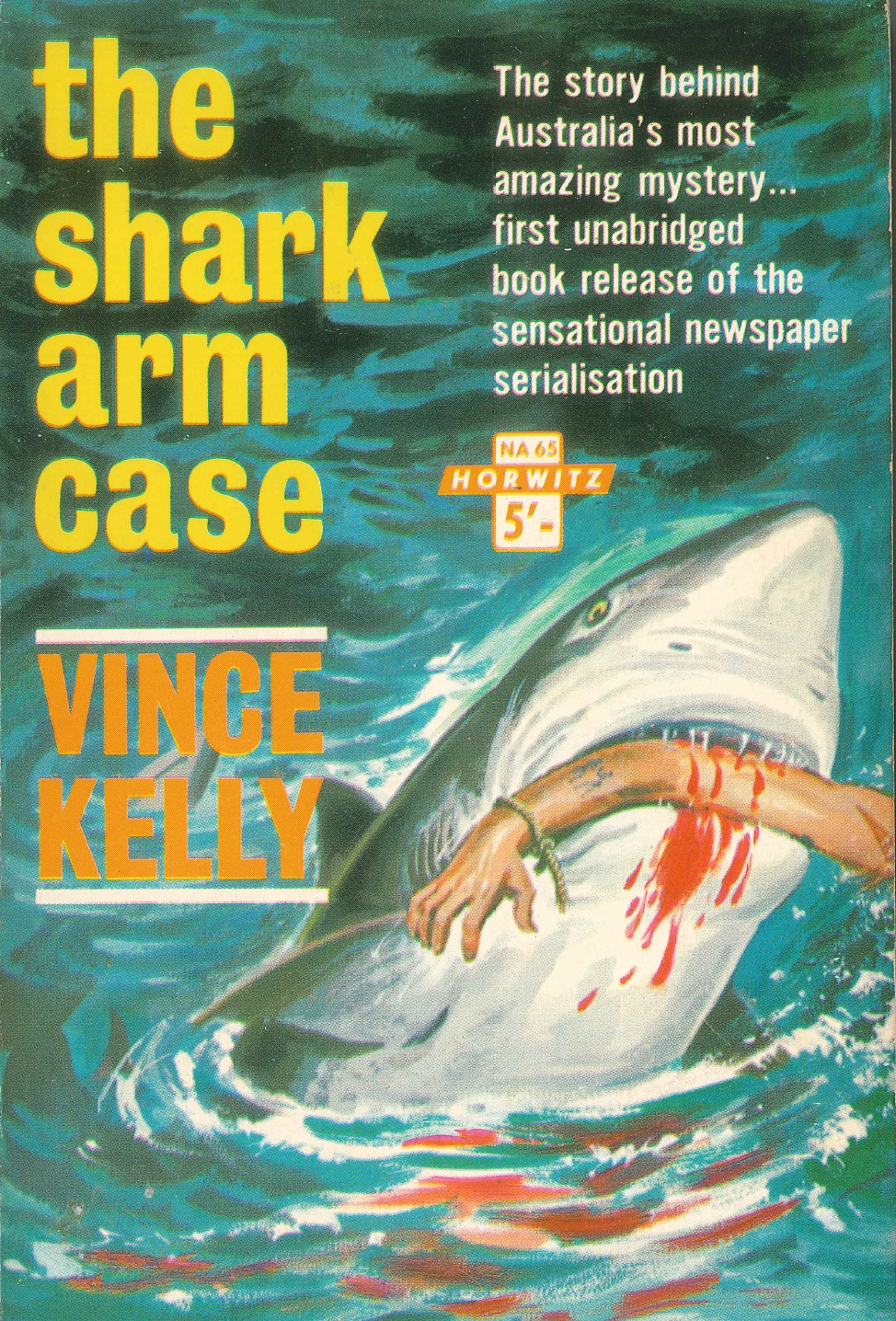

Vince Kelly, The shark arm case, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1975