The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Reynolds' cottages

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Reynolds' cottages

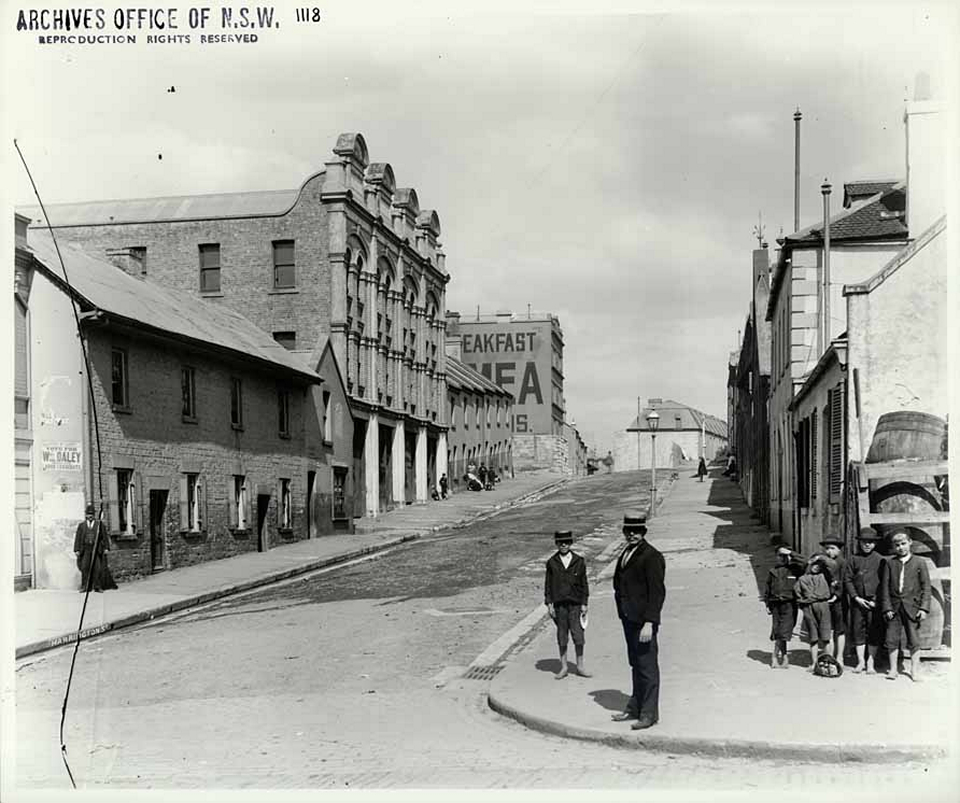

Reynolds' cottages are the earliest authentic dwellings in Sydney's historic precinct of The Rocks. Two of the three cottages were built by convicts in 1829 at 28–30 Harrington Street between Argyle Street and Suez Canal (previously Reynolds Lane). The third cottage at 32 Harrington Street was built by William Reynolds in 1834. A modern city has thrust up around them but Reynolds' cottages have remained the same – simple, sturdy and steadfast.

Unremarkable for their time, what is remarkable is that these working-class cottages have survived the many attempts to 'redevelop' The Rocks. From a convict blacksmith's house and forge to boarding houses to public housing to cafes and souvenir shops, the history of Reynolds' cottages is representative of The Rocks' evolution from a penal colony to a working-class neighbourhood to a heritage theme park.

Reynolds' cottages are located in the very hub of the early colony. Three months after the First Fleet arrived in Sydney Cove on 26 January 1788, the site was described in a convict sketch as being occupied by the house and garden of Lieutenant Bell, the General Hospital and garden, the bake house and women's camp. [1]

Markets were held at the nearby wharves until 1810. The site of Reynolds' cottages constituted part of the gardens of the Assistant Colonial Surgeon's House at 91 George Street. This house was occupied by Dr William Redfern and then Francis Greenway, both emancipated convicts who contributed greatly to the public health and architecture of the penal colony. The site of Reynolds' cottages was vacated when the Rum Hospital opened in 1815. The real estate scramble that ensued shows a particular window of opportunity for emancipated Irish convicts in a penal colony on the cusp of change.

Changing hands

The site was granted by Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1821 to William Hawkins, who then transferred the allotment to James Rampling, a baker, for £30. Rampling built and operated a bakehouse there until he was evicted in 1825 by Thomas Ryan, chief clerk in the Principal Superintendent Office of Convicts. Ryan, transported for forgery in 1817, produced documentation which stated that the land was granted in 1823 to John Gleeson by Governor Brisbane for a period of 21 years. Gleeson, who was transported from Tipperary aboard the Pilot with Ryan, then conveyed the lease to Ryan in 1826.

It appears that Thomas Ryan exploited his clerical position in the Colonial Secretary's Office to evict Rampling and build Reynolds' cottages. Ryan later admitted to burning four bushels of public papers in the Colonial Secretary's Office in 1820 when, as a clerk, he was entrusted with organising files upon the change of colonial government when Governor Brisbane commenced duties. [2] Rampling argued vehemently to retain his existing and legitimate business but was denied on the basis that he was still a Prisoner of the Crown, a status controlled by Thomas Ryan as chief clerk in the Principal Superintendent Office of Convicts. Rampling left, complaining in an 1827 memorial, 'How or in what manner these leases are obtained is mysterious'. [3]

Two cottages, now numbered 28 and 30 Harrington Street, were built by convict labour for Thomas Ryan in 1829. They are rare examples of small-scale colonial Georgian architecture which is characterised by symmetry and order. These working-class dwellings were originally one room deep, with the sandstone façade built onto the street line. The doors were a simple four-panelled design, with a brass doorknob in the middle, and flanked on either side by a sash window with shutters, with identical windows on the first floor. The roof was shingled, the walls were brick and the floors were timber. A well behind the cottages was dug to service the area.

William Reynolds, highwayman

In October 1830, Thomas Ryan sold the two cottages for £100 to William Reynolds, a blacksmith from County Meath in Ireland, who had been transported for life for highway robbery. Arriving in 1816 at the age of 32, Reynolds was assigned to serve Dr Redfern. When he absconded from his duties in 1820, he was described in the Sydney Gazette as:

William Reynolds, from Mr. Redfern's farm, aged 36 years, 5 feet 9 inches high, sallow complexion, grey eyes, had on a blue jacket, dark trousers and round hat, supposed to have a cross-cut saw and other implements for putting up post and rail fence. Speaks countrified. [4]

Reynolds obtained his ticket of leave upon marrying Ann Clarke in 1826. When they moved into 28–30 Harrington Street in October 1830, they used one cottage as a home and the other for William's blacksmith's forge. The following month, William's two teenage sons arrived from Dublin and, in August 1832, a teenage daughter arrived. All were born to Caroline Kelly – there is no record of her coming to Sydney. Ann Clarke died in December 1832.

Reynolds' cottages were the [media]beginning of an extensive property portfolio accumulated by William Reynolds. He built the third of Reynolds' cottages, now at 32 Harrington Street, in 1834. Francis Greenway claimed the site in April 1834, as well as the whole block on which Reynolds' cottages stands. Greenway had occupied 91 George Street since 1815, claiming endorsement from Governor Macquarie, but was evicted in 1834 in the Court of Claims. The Crown was represented by Frederick Wright Unwin, a solicitor and free settler.

In December 1838, Unwin was granted most of the block defined by Harrington, George, Argyle Streets and Suez Canal, with the exception of Reynolds' cottages, owned by Reynolds, and the allotment on the corner of Harrington and Argyle Streets, owned by the estate of the late Samuel Terry. Unwin subdivided the land between William Reynolds and Michael Gannon. Reynolds was granted a 21-year lease on the land behind the cottages, extending down to George Street. He built 101 George Street, as well as five substandard dwellings behind his Harrington Street cottages, and as many as could fit along Reynolds' Lane (now Suez Canal). This building frenzy responded to a housing shortage in the burgeoning colony, and contributed to the overcrowding and subsequent squalor caused by a lack of infrastructure that gave The Rocks a bad reputation.

William Reynolds died suddenly in 1841 when he fell off a ladder. Property had provided power and prosperity to the convicted and 'countrified' highwayman – he was described in his obituary as '… a man of considerable property and … highly respected amongst his brother tradesmen'. [5] The executor of his will was initially Michael Gannon and then Thomas Ryan. His extensive property portfolio of freehold on Reynolds' cottages and leasehold on surrounding properties was inherited by his two surviving children – Maurice, a solicitor, and Margaret, spinster, both living in the suburbs. His third child, William jnr, was an apprentice blacksmith who had died at Reynolds' cottages after a shooting accident at a pigeon match in Surry Hills in 1838.

The second generation

Maurice Reynolds, [media]solicitor and son of a highwayman, is representative of the emerging bourgeoisie which transformed the colony when convict transportation ended in 1840. Free settlers flocked in to seek their fortune and The Rocks was their first port of call. A demographic shift occurred as wealthier residents retreated to the suburbs and family homes became boarding houses to accommodate the hordes of free settlers and maritime workers. Two of the three cottages were boarding houses, while the third corner cottage was generally a grocery store.

Maurice was the first of a long progression of absentee landlords who allowed Reynolds' cottages to fall into disrepair while collecting their income. Evidently living beyond their means, Maurice and Margaret Reynolds mortgaged the property, first to John Brown in 1850 and then to Charles E Langley and George Stabler in 1857. Soon after the leasehold on the adjoining properties expired in 1860, Maurice Reynolds was declared insolvent. Margaret retained ownership of Reynolds' cottages but remortgaged to Langley and Stabler in 1861 and, upon Langley's death in 1864, to Stabler and John Blaxland. She finally conveyed her interest in Reynolds' cottages to Stabler and Blaxland in an indenture in November 1870. They sold Reynolds' cottages to George Rattray and William Henry Mackenzie in 1877 – more absentee landlords, more neglect.

Like his father and brother before him, Maurice died suddenly and violently when he fell off a horse in 1877. Margaret Reynolds died of 'senile decay' in the Hospital for the Insane in Parramatta in 1894. None of the Reynolds children married or left any heirs.

Tenants and changing surroundings

Reynolds' cottages became increasingly dilapidated, all listed in assessment books as in various states of disrepair. The Rocks was a working-class community with shameful associations to a convict history. From the 1870s, larrikins lurked and Reynolds Lane was the turf of the Rocks Push. Tenants included John Scoles, variously listed as a labourer, porter and carter, who lived in no 28 from 1861 to 1875, followed by the Day family who occupied the cottage for 21 years. Joseph Day was a mariner and, when he died in 1880, his widow and then his son ran a laundry there. The grocery store at no 32 was rented by a Mrs Brennan.

In 1884, Patrick Fahey became the first owner-occupier of Reynolds' cottages since William Reynolds himself when he purchased all three cottages from Rattray and Mackenzie. Fahey renovated and maintained the properties to an acceptable standard until his death in 1906, possibly saving them from the oncoming waves of demolition in the years to come as The Rocks became more overcrowded and the living conditions of the urban poor created a moral panic. Lurid media representation presented slum clearance as necessary for public health.

The Rocks was [media]resumed by the New South Wales government under the Darling Harbour Wharves Resumption Act 1900 when, after decades of neglect of sanitation in the area, the bubonic plague hit. Wholesale demolition ensued over the next 20 years as the Sydney Harbour Trust undertook a massive public works project to redevelop The Rocks and Millers Point. Reynolds' cottages survived but whole streets disappeared and rows of terraces were built to accommodate maritime workers. This was the genesis of public housing in Australia. Residents of The Rocks became public housing tenants of successive state government bodies – the Sydney Harbour Trust, then Maritime Services Board, and later the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority. Public housing strengthened the community, due to security of tenure and fixed rents. John Coutts lived in 28 Harrington Street from 1902–20, followed by Edwin J Branagan and then his widow. George Henry lived at 30 Harrington Street from 1909 till 1927. Reynolds' cottages survived more demolition as construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge and Cahill Expressway slashed through the area. The Rocks huddled in the shadows of progress, a community circumvented by traffic and trade.

Rampant post-World War II development threatened The Rocks once again, but the built environment was rescued by the green bans of the 1970s which protested against the loss of community and heritage caused by developers. Unfortunately, preserving the city's heritage came at the cost of the community. The Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority was established to relocate residents and develop the area from a working-class neighbourhood into a tourist precinct with the drawcard of Sydney's colonial history.

The [media]changing use of Reynolds' cottages indicates the progress of The Rocks through its various stages. In 1976, 28 Harrington Street became a café and antique store known as The Gumnut Teagardens, which remained in operation until April 2009. Public housing tenants were moved out of nos 30 and 32 in 1986 [media]when the courtyard behind Reynolds' cottages was excavated and no 30 was restored. In the process, a well was discovered underneath two outdoor lavatories behind nos 28 and 30. Rampling's oven was also found underneath the rubble behind no 28. [6] The courtyard was then left open to the public and, reflecting the folk culture which drew Sydneysiders to The Rocks, craftswomen moved in – a glass blower to no 30 and a wool shop in no 32, complete with a working loom.

At time of writing in mid-2012, 28 Harrington Street lies vacant in a relatively authentic state, retaining its original staircase. No 30 is a bicycle tour shop and no 32 is a souvenir shop. They remain the earliest authentic dwellings left in The Rocks.

References

Holmes, Melissa, Reynolds' cottages: Living History, Green Olive Press, Woollahra, 2010

Notes

[1] Fowkes, Francis, 'Sketch and description of the settlement at Sydney Cove Port Jackson in the County of Cumberland taken by a transported convict on the 16th of April 1788 which was not quite three months after Commodore Phillip's landing there', published by R Cribb, 288 High Holborn, 24 July 1789, accessed from National Library of Australia, MAP-NK 276, http://nla.gov.au/nla.map-nk276

[2] Sydney Gazette & NSW Advertiser, 25 October 1832

[3] Colonial Secretary, Correspondence, 1781–1825, State Records NSW, NRS 897, 4/1842A, pp 393–405

[4] Sydney Gazette & NSW Advertiser, 20 May 1820

[5] Sydney Monitor, 23 April 1841

[6] A. Wayne Johnson and Roger Parris, 'Report on Watching Brief During Excavations in the Rear Yards of 28-32 Harrington Street, The Rocks', project sponsored by Sydney Cove Authority, 5 March 1991