The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Reading the roads

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Reading the roads

At the beginning of the twentieth century, most of the streets of inner Sydney had been sealed and their hard grey surfaces lay like an empty slate waiting to be written on. [media]Lines to regulate traffic were the first messages to appear on the paving, and as motor vehicles became faster and the traffic became denser the number of regulatory marks grew. By the end of the century, the streets were covered with a vast lexicon of lines, signs, symbols and sentences that road users needed to memorise.

But traffic authorities are not the only scribes to write on the roadway. [media]There are many others who regard the pavement as a giant billboard for their public announcements, private messages, slogans, jokes and artworks. Their creative efforts mean that scanning the city's streets and laneways has become a literary adventure. With so many stories available for reading, it pays to keep your eyes on the road.

Regulating the unruly

Much of the writing on the road tells a story of struggle for territory and control. Between 1900 and 1930 the number of motorised vehicles on Sydney streets increased dramatically. Their speed and manoeuvrability meant that they were a danger to themselves and to other road users – pedestrians and the horse-drawn vehicles they had begun to supersede. [media]For safety's sake, new road rules had to be introduced, warning signposts erected, and regulations spelled out on the roadway itself. Paving had made the marking of streets possible and motorised vehicles made it necessary.

[media]In the early days the most common pavement markings were lines. Centre lines to keep vehicles to their own side of the road were initially painted by hand, but in 1938 the New South Wales Department of Main Roads purchased the parts for a motorised 'line striping machine' from the California State Highway Department. This machine was used mainly on rural highways but, in addition, in less than a year, 171 miles (275 km) of main roads in the Sydney metropolitan area had been marked with a centre line. [1]

Lines were also used to bring order to the free-for-all at intersections. [media]Early trials took place in King and Market streets in the city, where the police department painted white lines in 1928 in an attempt to deal with congestion. In the 1930s traffic authorities began using other kinds of road markers as well – metal studs, rubber pegs, and illuminated and reflective traffic domes. Suburban councils followed in their efforts to assert control over the streets. In 1948 Petersham Municipal Council was able to boast:

In the provision and maintenance of road safety facilities such as signs, traffic domes, the marking of traffic lines on roads and other such measures, the Council has always co-operated whole-heartedly with the Department of Road Transport and the Police Traffic Department. Traffic conditions in Petersham both for vehicles and pedestrians are now as safe and convenient as possible. [2]

Styles of road lines have changed – solid centre lines were replaced by dotted lines when paint became scarce during World War II, yellow paint was replaced by white. The original painted lines in Sydney have long since been erased or overwritten. As the volume of traffic that needs to be regulated has grown, the interplay between road users and authorities has driven a massive increase in the variety and quantity of regulatory marks. A bonus for Sydney road-readers is discovering the occasional relic of an old-style marker – metal buttons in the asphalt, for instance, or one of the few remaining traffic domes – or finding places where private citizens have taken the law and the paintbrush into their own hands and applied warnings to danger spots on the street.

Territorial claims

The proliferation of vehicles has meant greater demand for parking spots. Street signs have become necessary to regulate not only moving but standing still. [media]In addition to the official demarcations there are hand-painted versions, and some of the most extravagant of these can be found in the narrow streets and back lanes of inner city areas, where residents defend access to their garages and driveways. The battle over territory is greatest where local attractions bring hordes of day (or night) trippers from outside the area.

Cross walkers

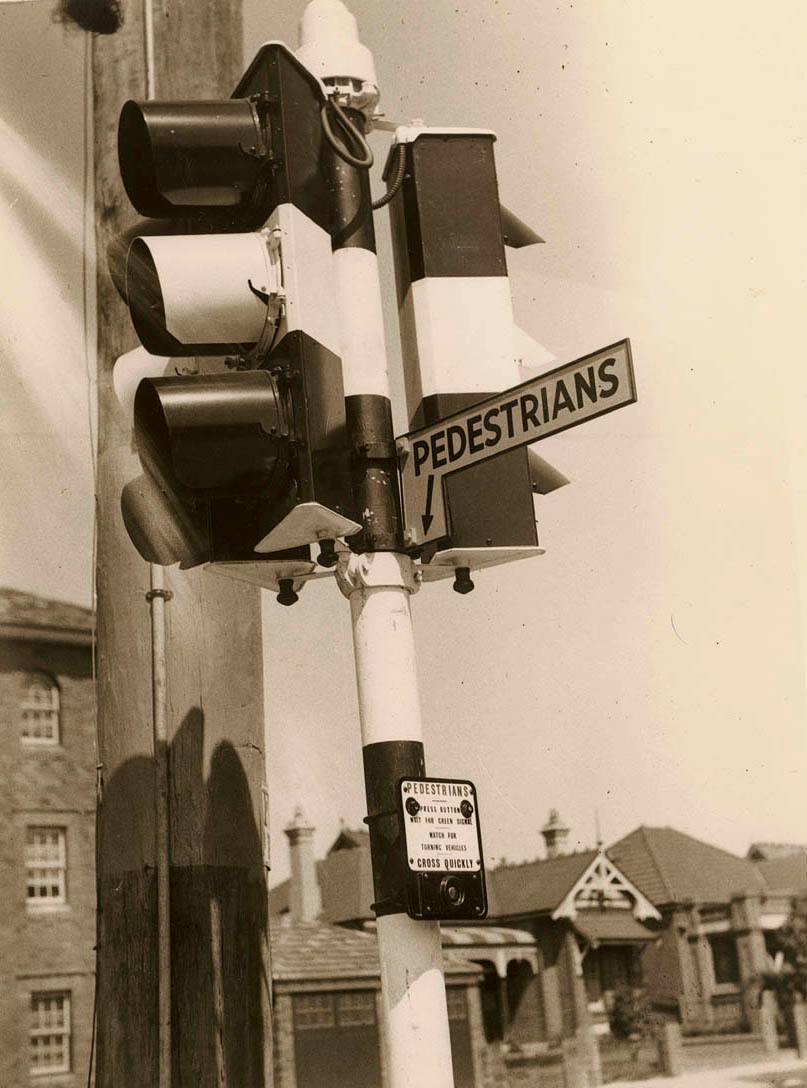

[media]Given that it was motorised traffic that made marking on the streets necessary, it is ironic that some of the most noticeable pavement signs are there to marshal pedestrians. For their own safety, walkers are meant to cross in herds at designated places. As early as 1912 the Sydney City Council was considering alleviating the danger to pedestrians at Circular Quay by lengthening the white markings that denoted stopping places for vehicles. These lines were to be extended from pavement to pavement to provide a safe crossing area. [3] By the 1920s designated pedestrian crossings in the city were marked with metal studs or a pair of white lines. [media]The striped zebra crossings were introduced in the 1950s.

[media]But just as people traversing a park will wear away the grass in routes that don't necessarily coincide with designated pathways, so pedestrians choose street crossings that are not necessarily those indicated by municipal authorities. At some problematic intersections, individuals even exert their will by defiantly painting their own zebra crossings.

Crooked crosswalks are not the only handwritten forms of pedestrian resistance. Vestiges of organised protests remain in places such as Newtown, where the Reclaim the Streets collective was allowed to hold its annual party on King Street for several successive years in the late 1990s. Traffic was blocked, entertainment was provided, and celebrators set about painting the road with slogans and decorations. A few days later, the writing would be obliterated by the local authorities, leaving a layered archive of successive Reclaim the Streets takeovers. The traces are faint except in one spot, a traffic island on Newtown Bridge, where a garish arrangement of flowers made in 1999 has been preserved.

Casualties

[media]Reminders of the dominance and danger of motorised vehicles can be read in collections of other esoteric marks on the streets. These are the onsite records methodically spray-painted by police at the scene of serious traffic accidents. Crash investigators returning to the site later use these patterns of angles and arrows to decipher the causes of the event. The diagrams remain long after the debris has been cleared away, serving as semi-permanent markers of 'black spots' on the road and as memorials to sometimes tragic events.

Pedestrians are killed more often than motorists on New South Wales roads, and traffic authorities try all sorts of tactics to remind people of this sobering fact. [media]In the late 1990s, local councils in inner city suburbs joined with the RTA (Roads and Traffic Authority) in a safety campaign where body outlines were stencilled at pedestrian danger spots. Those flattened jaywalkers still haunt some street corners like faded ghosts.

Mementos

Some remnant marks on the road are reminders of calamities, but others recall celebratory times – such as the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games. The blue ribbon event of the games was the marathon whose 42-kilometre route, marked with a blue line, wound through some of the city's most telegenic locations. [media]The memory of Sydney's triumphal hosting of the Olympics is now preserved in sections of the blue marathon line that have been allowed to remain in places where they do not constitute a road hazard.

Another pavement souvenir of the Olympics is not generally recognised, but in 2000 'LOOK RIGHT' stencils began appearing beside city kerbs as a warning to pedestrians. This measure anticipated the influx of overseas tourists needing to be reminded that vehicles in Australia drive on the left-hand side of the road.

Public notices

There's always something to celebrate in Sydney, always something on, and it used to be possible to find out what by reading the road. Organisers of alternative dance parties regarded the pavement as free advertising space – their arcane stencils colonised zebra crossings and safety signs. But that was in the 1990s and fashions in self-promotion change. In 2008 there are fewer stencils for raves, but garage bands still sometimes splash out with street-wide headlines to publicise themselves.

[media]For these and many other Sydneysiders, the pavement is not simply a thoroughfare but a publicly available space for their own personal, political or artistic expression. Written on the roadways are stories of democratic engagement, of youthful exuberance, of romance, disappointment and pain.

Handmade works on the roadway are seldom produced impetuously. The act of creating them requires premeditation, planning, and physical daring. The reward for this effort can be an audience of thousands, although it is this same audience that will eventually wear the works away. Nevertheless, bold gestures like these demonstrate that the paved streets of Sydney have not been entirely ceded to the motor vehicle.

Notes

[1] 'Line marking machine', Main Roads, vol 9, no 4, August 1938, pp 135–136; 'Traffic lines', Main Roads, vol 10, no 4, August 1939, p 109

[2] Allan M Shepherd, The Story of Petersham 1793–1948, The Council of the Municipality of Petersham, Petersham, December 1948, p 43

[3] John R Wigg, 15 April 1912, City of Sydney Archives 335088 1912/1739

.