The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Neptune

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Neptune

Neptune [media]was the most notorious of the six Second Fleet ships to arrive in New South Wales in 1790. The voyage of these three convict transports in 1790 had the highest mortality rate in the history of transportation, [1] earning it the moniker 'The Death Fleet'.

The first three ships of the Second Fleet, the female convict transport Lady Juliana, supply ship Justinian and Royal Naval storeship HMS Guardian, left for Australia the previous year. Lady Juliana was chartered by First Fleet contractor William Richards junior, while Neptune, Scarborough and Surprize were chartered by slave traders Camden, Calvert & King at a considerably lower rate than Richards. [2] The dissension that plagued the voyage began even before the ships left England, as government officials and contractors argued over where their authority lay, and concerns were raised about the severity of the irons used on the convicts. [3]

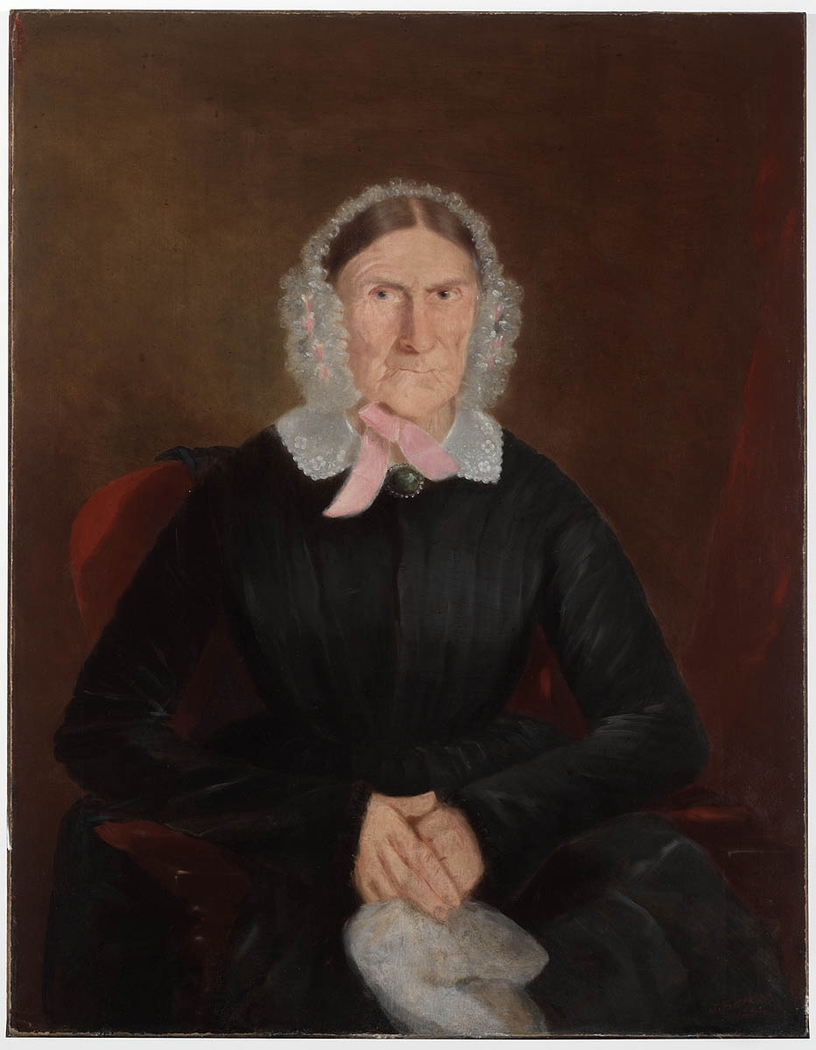

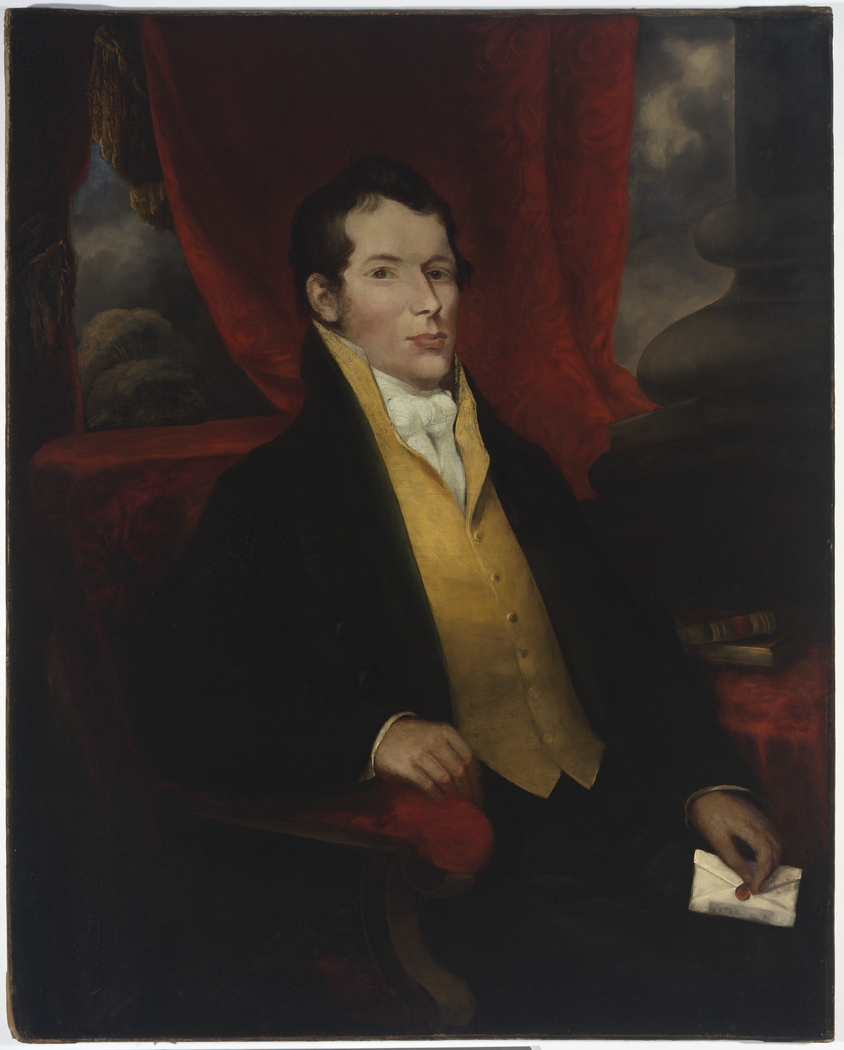

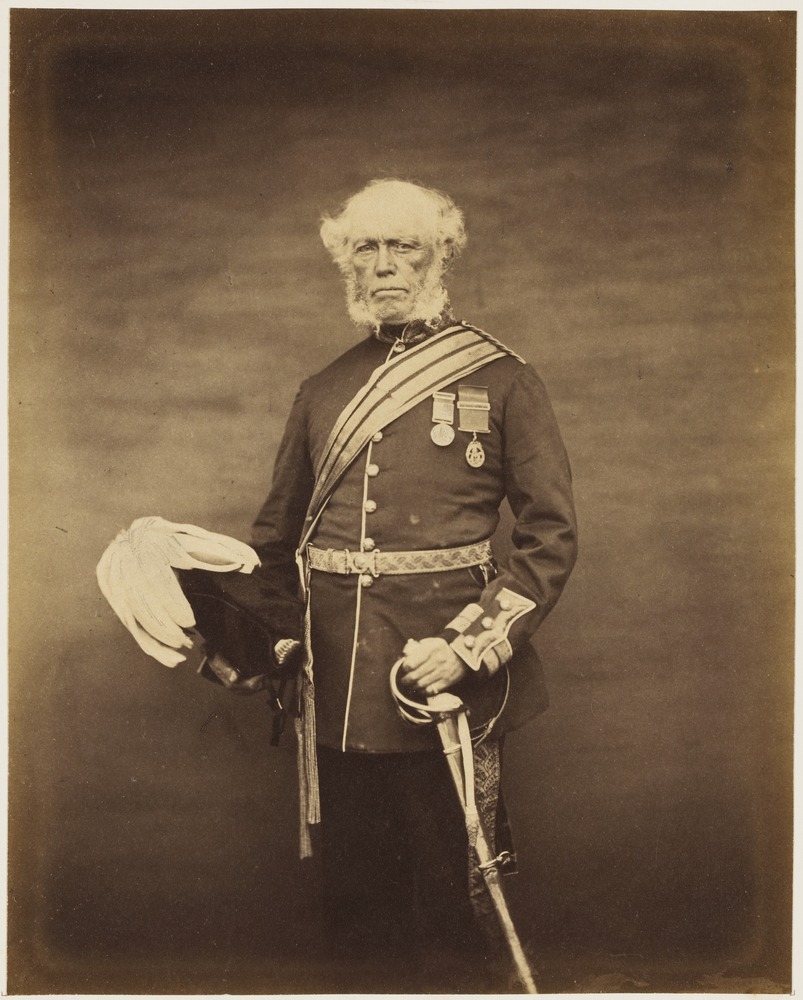

Neptune [media]was built on the Thames in 1779 and at 809 tons [4] was the largest ship of the Second Fleet. Neptune's sailed with 499 convicts (421 male, 78 female), [5]. [6] Also onboard was surgeon William Gray, a crew of about 83 [7], and the fleet's Naval Agent, Lieutenant John Shapcote, whose duty it was to ensure the terms of the contract were met. In addition, seven officers and 44 men of the New South Wales Corps, six of their wives (including Mary Bray and Diana Haddock) and three soldiers’ children [8] sailed on Neptune, as did six free wives of convicts and five of their children given a free pass to the colony. The soldiers formed part of a new infantry corps sent to replace the marines who had sailed with the First Fleet. The corps included Captain Nicholas Nepean, and Lieutenant John Macarthur,[media] his wife Elizabeth and son Edward. Elizabeth's journal is a valuabe firsthand account of the voyage of the three ships. D'Arcy Wentworth, a trained surgeon, [media]travelled on Neptune as a passenger and along with the Macarthurs, became a central figure in the development of the colony and the early history of New South Wales.

[media]Prior to departure, a conflict between Macarthur and Neptune's original master Thomas Gilbert led to a bloodless duel at Plymouth and the dismissal of Gilbert, who was replaced by Donald Trail, originally of Surprize. [9] Elizabeth Macarthur was happy [media]to see the back of Gilbert, feeling assured that 'such another troublesome man could not be found'. Unfortunately, Trail's character proved to be of a 'much blacker dye' [10] and as a result of continuing tensions between the Macarthurs, Nepean and Trail, the Macarthurs transferred to Scarborough one month into the voyage. Elizabeth wrote of the exchange, ominously describing Trail as 'a perfect sea-monster'. [11]

When Neptune, Scarborough and Surprize departed English waters on 17 January 1790 they carried, along with their convict cargo, stores of flour, salt beef and pork. [12] Neptune was the only one of the three to transport female convicts and the Navy Board issued orders stipulating that the women were to be kept separate and not abused or ill-treated. [13] The women were unchained and housed in a section of the upper deck and had more liberties than Neptune's male convicts who were confined in filthy conditions primarily on the orlop deck (third from the top), [14] receiving inadequate rations and were chained together [15] in 'barbarous' irons. [16]

By the time the fleet arrived in Cape Town on 14 April many of the convicts were ill with scurvy and 45 men and one woman had already died on Neptune. [17] At Cape Town, Shapcote obtained fresh food supplies for the convicts and grudgingly arranged to make room on the three convict transports for stores salvaged from the wrecked supply ship HMS Guardian. Twelve of Guardian's surviving convicts were also transferred to Neptune. Neptune, Scarborough and Surprize remained at the Cape for 16 days, commencing the final leg of the voyage on 29 April 1790. [18]

Shapcote did not survive to see Australia, dying suddenly in the early hours of 12 May. Shapcote's son had sailed to Australia on the Second Fleet storeship Justinian and boarded Neptune on its arrival into Sydney Cove on 28 June 1790, only to be met with the news of his father's death. [19]

As the convicts were disembarked, the full extent of their mistreatment became apparent. Of over 1,000 convicts, half arrived sick and 270 died on the passage. On Neptune the mortality rate was the highest, with deaths totalling around 150 men and 11 women. In 1791 a number of Neptune crew members lodged statements alleging cruel treatment of the convicts on the ship and in 1792 legal action was taken against Donald Trail and Neptune's chief mate William Ellerington, although it ended in acquittal in June of that year. [20]

Despite the Second Fleet's reputation and high mortality rate, many of the convicts who survived prospered in their new homeland, making significant contributions to the growth of the colony. George Salter, transported on Neptune for his part in the murder of two officers during a smuggling raid in 1787, became a successful farmer with 30 acres (12 hectares) of land granted to him in 1796 in the Crescent, Parramatta. The house that Salter built soon after receiving his grant is one of the only surviving eighteenth-century houses in Australia and the earliest to be associated with a former convict. [21] [media]Similarly, young convict William Baker rose to success and wealth as a farmer, retail trader and publican after his transportation in Neptune for theft, able to describe himself in his will as a 'gentleman'. [22] Female convict Molly Morgan, transported for the crime of theft, arrived in Sydney in Neptune only to escape in the storeship Resolution with 13 other convicts. Morgan returned to England but was transported again in 1804. [23] In 1819 she settled in the Hunter River district where she became a farmer, grazier and publican. Morgan married a man 30 years her junior and was one of the founders of the township of Maitland. [24]

On 19 August 1790 Neptune was cleared and discharged, and all its cargo landed. The ship sailed from Sydney Cove on 22 August but was delayed by the discovery of several convicts on board attempting to escape. [25] Neptune reached Canton on 7 November to take on a cargo of tea and other goods for the East India Company. Along with the other Second Fleet transports Lady Juliana and Scarborough, and storeship Justinian, Neptune returned to England in October 1791. [26]

In 1796 Neptune was destroyed by fire while moored in Cape Town. [27]

Further reading

Bateson, Charles. The Convict Ships, 1787–1868. Glasgow: Brown, Son & Ferguson, 1969.

Collins, David. An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales; With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, volume III, 1798. Edited by H Fletcher. Sydney: AH & AW Reed in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, 1975.

Flynn, Michael. The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790. Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001.

Rowan Hackman. Ships of the East India Company. Gravesend: World Ship Society

Macarthur, Elizabeth. Journal entry Sunday 13 December 1789 in Some Early Records of the Macarthurs of Camden. Edited by Sibella Macarthur Onslow. Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1914.

Notes

[1] Charles Bateson, The Convict Ships, 1787–1868 (Glasgow: Brown, Son & Ferguson, 1969), 31

[2] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 23

[3] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 27

[4] Lloyd's Register 1790 (London: The Gregg Press)

[5] Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson (London: G Nicol and J Sewell, 1793), available online at University of Sydney Library, http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/ozlit/pdf/p00044.pdf, 39

[6] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 32

[7] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 30

[8] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 27

[9] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 31

[10] Elizabeth Macarthur, journal entry Sunday 13 December 1789 in Some Early Records of the Macarthurs of Camden, edited by Sibella Macarthur Onslow (Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1914), 7

[11] Elizabeth Macarthur, letter to her mother dated 20 April 1790 in Some Early Records of the Macarthurs of Camden, edited by Sibella Macarthur Onslow (Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1914), 17

[12] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 32

[13] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 33

[14] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 32–33

[15] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales; With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, volume III, 1798, edited by H Fletcher (Sydney: AH & AW Reed in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, 1975), 129

[16] William Hill, letter to Jonathan Wathen, 26 July 1790 (copy), State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library, MLMSS 6821, online at http://www.acmssearch.sl.nsw.gov.au/search/itemDetailPaged.cgi?itemID=402753

[17] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 44

[18] Charles Bateson, The Convict Ships, 1787–1868 (Glasgow: Brown, Son & Ferguson, 1969), 127

[19] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales; With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, volume III, 1798, edited by H Fletcher (Sydney: AH & AW Reed in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, 1975), 131

[20] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 63

[21] Michael Flynn, 'George Salter and his house 1796–1817', unpublished research report, available online at University of Sydney Library, http://dx.doi.org/10.4227/11/5045887EC9ACB, viewed 3 February 2016

[22] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 90

[23] Elizabeth Guilford, 'Morgan, Molly (1762–1835)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/morgan-molly-2480/text3333, published in hardcopy 1967, accessed 3 February 2016

[24] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 103

[25] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales; With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, volume III, 1798, edited by H Fletcher (Sydney: AH & AW Reed in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, 1975), 135

[26] Northampton Mercury, Saturday 8 October 1791, 1

[27] Rowan Hackman, Ships of the East India Company (Gravesend: World Ship Society, c2001), 161

.