The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

La Perouse

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

La Perouse

The history of La Perouse is closely linked with Sydney's earliest European history. The ill-fated French navigator, after whom the place was named, arrived just days after Captain Phillip's first landing at Kurnell, on the opposite shore. Many European Australians' memories of the suburb involve stories of hardship and struggle. Hundreds of unemployed people camped there during the depression of the 1930s and again after World War II. Intertwined with these memories are the histories of Aboriginal Australians, for whom La Perouse is a place that marks a significant beginning. It is a different sort of beginning, not a triumphant story of the coming of civilisation, but the beginning of the invasion, of dispossession and degradation. Yet La Perouse is the only Sydney suburb where Aboriginal people have kept their territory from settlement until today, and its history is a story of the survival of culture in the face of European invasion.

La Perouse is situated 14 kilometres south of the city of Sydney on the northern headland of Botany Bay and is part of the Randwick municipality. The La Perouse section of Botany Bay National Park extends from Cape Banks to Bare Island and has over 350 species of plants. [1] La Perouse has an extensive foreshore and at the right time of year, Henry Head provides a good whale-watching point.

First inhabitants

The original owners of the land were the Kameygal, and their proximity to the coast meant that they enjoyed a plentiful supply of fish. The area also had fresh water supplies and places of natural shelter. The Kameygal travelled with the seasons, and established relationships with other Aboriginal people along the New South Wales south coast. Today, many residents at La Perouse have strong connections with the Aboriginal community at Wreck Bay. La Perouse is the one area of Sydney with which Aboriginal people have had an unbroken connection for over 7,500 years. [2] Members of the Timbery family living in La Perouse today can trace their ancestors back to pre-contact times. The decision of the colonisers to name the place after La Perouse, a French navigator who stayed in the area for just six weeks, symbolically denied that the people already occupying the area were the owners of the land.

Europeans arrive

To stand on the La Perouse peninsula and look down upon the expanse of glistening ocean, is to be reminded of the beauty of the natural environment. However, it was not the beauty of the place that Governor Phillip noted when he landed at Botany Bay in 1788. Instead, he deemed La Perouse unsuitable for settlement because the area was too exposed, the ground was too spongy and there was a lack of fresh water. Phillip also called it an 'unhealthy' spot for settlement, due to the swampiness of the area, and he set out to find 'a proper situation for the settlement', which would later be known as Sydney Cove. [3] On the way out of Botany Bay, he saw La Perouse's ships, the Astrolabe and the Boussole, entering the bay. La Perouse was on a scientific expedition and needed to replenish his supplies and rest his crew. The beach he landed on was later named Frenchmans Beach. He remained for six weeks, setting out to return home on 10 March 1788, but was never heard from again. The ruins of his ships were discovered decades later, off the coast of what is now Vanuatu. [4] During the six-week stay, Father Receveur, a Franciscan chaplain, died and was buried at La Perouse. [5]

[media]In 1825, a French explorer, Hyacinthe de Bougainville, visited La Perouse and arranged for a monument to be built in memory of Captain La Perouse and a memorial to be built at the site of Father Receveur's grave.[6]

Governor Phillip was not alone in deeming La Perouse unsuitable for settlement. In 1812, Governor Macquarie officially closed the northern headland of Botany Bay to settlement. It was believed that the land around Botany Bay was barren and unfertile, although it was renowned for its native flora.

Government buildings

Various government projects were undertaken in the area during the nineteenth century. A watchtower was built in 1822 on the highest point of the headland at La Perouse, which had views of the entry to Botany Bay. Troops were stationed in the watchtower to keep watch for smugglers. [7] From 1833 until 1903, the watchtower took on the role of a customs house. In the 1860s it was also used as a school. This tower still stands, making it the oldest structure in Botany Bay and the oldest customs house in New South Wales.

La Perouse was connected to the city by road in 1869. The first telegraph cable between Australia and New Zealand was built at La Perouse in 1876. [8] This cable station was later used as an extension of the Coast Hospital during the Spanish influenza epidemic of 1918–20. Between 1920 and 1933, it was used as accommodation for nurses and following this, the Salvation Army established a refuge for women and children here. This was closed in 1987, and in 1988, the La Perouse Museum and an Aboriginal cultural centre were established in the old cable station.

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, La Perouse was used as a place to isolate people suffering from smallpox and other infectious diseases. It was close to Sydney but far enough away for isolation and it was not a residential area. In 1881, a Sanitary Camp was established at Little Bay for some victims of the smallpox epidemic of that year. 1885 saw renewed outbreaks of smallpox and also typhoid in Sydney and the colonial government decided to establish a permanent hospital at Little Bay to treat infectious patients.

In 1881, fortification work began on Bare Island, a tiny island at the mouth of Botany Bay. The fort was decommissioned in 1911 and between 1912 and 1963, it was used as a war veteran's home. Fortifications were also established at Henry Head between 1892 and 1895, with operations ceasing in 1910.

During the 1930s, fortifications and barracks were constructed near Cape Banks on land owned by the military. During World War II, La Perouse became an important site for defence. The batteries at Henry Head and Cape Banks were strengthened and brought back into military service and Bare Island Fort was briefly re-commissioned. Also during the war, La Perouse became the site where Australia's alliance with France was symbolically expressed; Bastille Day was first celebrated at La Perouse during these years and is still celebrated there today. [9]

Aboriginal La Perouse

1878 marked a change in the nature of the Aboriginal community at La Perouse. [10] Aboriginal people from the south coast moved to Sydney to seek employment or government rations and some moved to La Perouse, probably because it was a good fishing site. During the early 1880s, the Parkes government was under increasing pressure to take action on Aboriginal affairs and in 1882 Sir Henry Parkes appointed George Thornton as Protector of Aborigines. [11] Thornton believed that Aboriginals should be removed from urban locations, yet he did honour the request of five Aboriginal men and their families to be allowed to stay at La Perouse. He justified his decision to Parliament by arguing that the camp was economically viable, in contrast with other camps in Sydney, which were seen as parasitic and a nuisance to society. Thornton organised for huts to be built for people camped at La Perouse. [12] By 1881 there were approximately 50 Aboriginal people living in two camps in the Botany Bay region, 35 at La Perouse and the remainder at Botany Bay. The people were free to travel between the two camps.

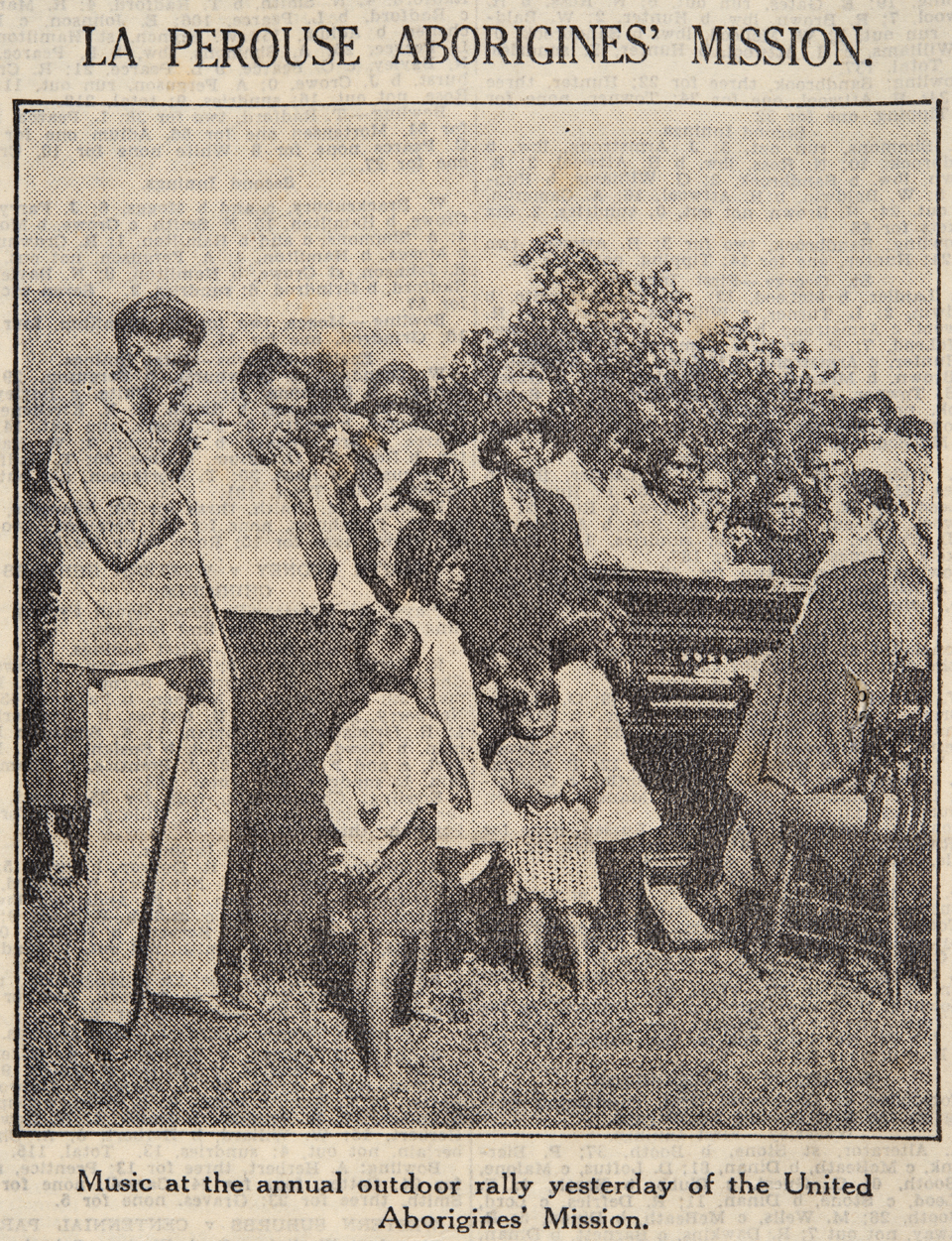

In 1883, Thornton was replaced by the Aborigines Protection Board which followed a more isolationist and protectionist policy. The Board established reserves, which effectively segregated Aboriginal people from white Australians throughout New South Wales. By 1885, seven acres (three hectares) of land at La Perouse had been officially declared a 'Reserve for the Use of Aborigines' the only one in Sydney. [13] Several missions were involved with the reserve at La Perouse, the most significant being the La Perouse Aboriginal Mission (later called the UAM) which was founded by white Protestants. [14] Iris Williams, who lived on the reserve, recalls her mother preaching at the small tin church and giving funeral sermons. [15]

Day trippers

The very factors which made La Perouse seem an unattractive place to live – its isolation and absence of white settlement – made it attractive to city residents for day trips. From the mid-1880s, the peninsula began to attract curious city dwellers for weekend visits. They came on Sunday afternoons to see the 'natives', the living relics of pre-colonial Australia. This was a cause of concern to both the Aborigines Protection Board and the UAM and led to further restrictions upon the freedom of Aboriginal people at La Perouse. Any attempt to develop the land for recreational purposes, such as building a hotel or a pub, was blocked by the Aborigines Protection Board.[16] In 1895 the reserve was enclosed by a fence and only the local constable and the resident missionary had a key. Aboriginal people on the reserve were literally locked in. When the Department of Fisheries introduced a licensing system in New South Wales, Aboriginal people were prevented from selling fish at the markets. They were only able to fish for personal consumption, and even this was restricted by the actions of local fishermen. The Aborigines Protection Board was also concerned that Aboriginal people from outside Sydney would travel to La Perouse and from there gain access to the city. Thus, restrictions were placed upon boat and rail travel for Aboriginal people in La Perouse who wished to travel to Sydney. In 1897 the Aborigines Protection Board rejected requests from missionaries for more huts and increased rations because it was thought that such action would encourage more people to move from the south coast to La Perouse. [17]

Resistance and continuity

The same year, amid concerns about the interaction between Aboriginal people at La Perouse and white tourists, the Aborigines Protection Board decided that the place was no longer suitable for Aboriginal occupation. Both the New South Wales Department of Lands and missionaries on the reserve disagreed with the Aborigines Protection Board's decision, arguing that it would be difficult to move the Indigenous population because of their long history of occupation of the area. Nevertheless, by 1900, the Aborigines Protection Board had decided that it would relocate Aboriginal people from La Perouse reserve to Wallaga Lake on the south coast. The people refused to move, despite the fact that the Aborigines Protection Board reduced, and eventually ceased supplying, rations. By 1902, it seems that the Aborigines Protection Board had given up and resumed supplying rations to those on the reserve. In 1908 there were 73 people living on the reserve. During 1908, new houses were built and by 1912, the population on the reserve had grown to 106. In 1915 there were 124 people living on the reserve.

The Aborigines Protection Board could not stop non-Aboriginal Australians making day trips to La Perouse, which became easier after the tram line was built in 1902. Aboriginal residents participated in the tourist industry, selling boomerangs and other souvenirs. From about 1909, 'snake men' drew many tourists [18]. These snake men would allow snakes to crawl over them and sometimes bite them, in a pit just near the Loop where the tram from Sydney terminated. [19] Many people who grew up on the Aboriginal reserve have happy memories of the visiting tourists. Beryl Beller remembered collecting shells with her mother to glue onto various cardboard cut-outs and sell to tourists. Lee-Anne Mason recalled waiting in anticipation for the weekend tourists to arrive. People would 'be flocking in all day' to watch Mr Cann, the snake man. She also recalled diving for pennies and how she would always manage to catch the penny before it hit the sand. [20]

[media]The question of moving Aboriginal people from La Perouse re-emerged during the 1920s. Randwick Council wanted the reserve moved, in the interests of big business. The South Kensington and District Chamber of Commerce wrote to the Aborigines Protection Board expressing concerns about housing conditions, sanitation of the reserve and its 'morality.' [21] The Aborigines Protection Board agreed that the reserve should be moved. Again, the people on the reserve refused to move. In 1928, a petition signed by 53 reserve residents was published in the Sydney Morning Herald. It read,

We, the undersigned aborigines of the La Perouse reserve, emphatically protest against our removal to any place. This is our heritage bestowed upon us: in these circumstances we feel justified in refusing to leave. [22]

As a compromise, Randwick council converted part of the reserve into a public recreation area and moved the huts away from the waterfront. [23]

During the 1920s, La Perouse people became politically active in support of land rights, particularly through involvement in the Australian Aborigines Progressive Association (AAPA, later called the APA). Jack Patten, from La Perouse, was one of the leaders of the APA and Joseph Timbery, Wesley Sims, WG Sherrit, R McKenzie and Tom Foster all played a significant role in the 1938 Day of Mourning, which was held to mark Australia's sesquicentenary. [24]

Depression shantytowns

[media]During the Depression, beginning in 1929, hundreds of unemployed people moved to La Perouse. [25] It was a perfect area for camping, close to the ocean with access to fresh water and natural shelter. [26] There were three separate camps: Hill 60, Frog Hollow and Happy Valley. [27] Happy Valley was the largest of the three camps, with about 300 people living there. It was located at the end of Anzac Parade in a gully, which provided shelter from the strong winds. Frog Hollow was an Aboriginal camp near the reserve. [28] Many of those who set up camp at Frog Hollow were relatives of people living on the reserve. The camp offered a measure of freedom that was not found on Aboriginal reserves. White and black children attended the same school; this was unusual at a time when government policy was geared towards keeping European Australians and Aboriginal Australians separate. Many children did not see any significant differences between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children. One woman recalled that when someone raised the alarm that 'the welfare's coming' (meaning that the child welfare department had come to take Aboriginal children), both white and black children would run and hide in the bush, the white children unaware that the child welfare department had come only for Aboriginal children. [29]

Although the depression had eased by 1934, the shanty towns remained. Happy Valley was closed in 1938, while Frog Hollow and Hill 60 remained during the Second World War and after. Following the closure of Happy Valley, a scheme to provide cheap housing was introduced. The houses were shaped like butter boxes and were only half built – the rest was left to the residents to build. [30] They did not have water, connection to sewerage or electricity. Although intended for white Australians, the scheme did allow some Aboriginal people to buy houses outside the reserve. [31] Employment opportunities for Aboriginal men in La Perouse increased with the building of an oil refinery in Matraville in 1948. [32] Aboriginal women were employed as maids and cooks at the Coast Hospital, in nearby factories and as domestic servants. Such employment was important to the survival and growth of the Aboriginal community in La Perouse. [33]

During the Depression, the majority of non-Aboriginal people who had moved to La Perouse had Anglo-Celtic origins. However, during the 1940s and 1950s, there was an influx of 'new Australians', from Poland, Russia, Ukraine and Malta. Many of these people were employed but homeless, as a result of a severe housing shortage in Sydney. [34] During the 1950s, many of the shacks were demolished and in 1954 Frog Hollow was closed. Some non-Aboriginal people were forced to move and Aboriginal people who had camped at Frog Hollow moved back to the reserve or in with relatives living around it.[35]

Land rights at last

[media]During the 1960s, the Mayor of Randwick wanted to close the Aboriginal reserve, to improve the image of La Perouse. Jack Horner, honorary secretary of the Aboriginal- Australian Fellowship wrote repeatedly to Randwick Council as well as to the state and Federal governments asking for improved housing conditions and opposing the relocation of the reserve. He helped organise a petition to stop the closure of the reserve. [36] As before, Aboriginal Australians at La Perouse refused to move and eventually the plan to move them was abandoned.

In 1966, Aboriginal land rights in New South Wales became a heated political issue. A Joint Parliamentary Inquiry into the Welfare of Aboriginals turned its attention to the reserve at La Perouse. The reserve was a stark reminder that the official policy of assimilation had many ambiguities and contradictions. Assimilation had been intended to gradually incorporate Aboriginal people into wider society, yet here they were living separate from, and in worse conditions than, the majority of white Australians. Although the Aborigines Protection Board and the local council advocated closure of the reserve, the Inquiry recognised the connections between Aboriginal people and the land and instead proposed a plan known as the 'Endeavour Project.' This would create a village where Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people would live together. The project never eventuated because Aboriginal people on the reserve argued that they had the right to keep the reserve Aboriginal only. Instead, the reserve was redeveloped in 1972 and in 1973 it was handed to the New South Wales Aboriginal Lands Trust. Reserve residents filed a land claim to have ownership passed to them and in 1984 the La Perouse Local Aboriginal Land Council was given the deeds to the reserve. [37]

In the lead up to the 1988 Bicentenary, Aboriginal affairs again emerged as a political issue. On 26 January 1988, the Bicentenary was celebrated with a re-enactment of the arrival of the First Fleet. The re-enactment, staged at Botany Bay, was met with hostility from Aboriginal Australians as well as some non-Aboriginal Australians, who gathered at La Perouse to protest. On the same day, a march from Redfern Oval to Hyde Park celebrated Aboriginal survival of 200 years of invasion and violence. After the march, many returned to La Perouse and Kurnell for an all-night festival to signify new beginnings and reinforce connections with the land. Dance fires burned in the dark and people danced for hours, stopping only at sunrise. By 1992, this celebration had been formalised into the Survival Day concert, held annually at La Perouse. It is the largest national annual celebration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders arts and culture. [38]

La Perouse today

In 2008, there are about 420 people living in La Perouse. Over one-third of the population is Aboriginal. In August 2005, the local Aboriginal community signed a shared responsibility agreement which was intended to deliver housing improvements in return for residents paying rent to the La Perouse land council and documenting their histories. [39] These repairs are yet to eventuate.

On Sundays people still crowd around the snake pit to watch the 'snake man' perform. There are tours of the museum and Bare Island Fort. La Perouse remains a popular place for families to visit, for a picnic on the grassy headland, a swim, or a walk through the national park.

Many different memories and meanings are associated with La Perouse. The monuments and buildings are visual reminders of its post-settlement history. Its pre-settlement history is not as obvious. The rock engravings of a whale and its calf, as well as one of a shark, are faded and will continue to wear away. [40] Yet unlike the engravings, the connection that Aboriginal people living at La Perouse have with the land has not faded. Their stories provide a rich and diverse history of La Perouse and are testament to the cultural continuity of the Aboriginal community.

References

La Perouse: The Place, the People and the Sea: a collection of writing by members of the Aboriginal community, Aboriginal Studies Press for the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1988

Maria Nugent, 'Revisiting La Perouse: A Post-Colonial History', PhD thesis, University of Technology, Sydney, 2000

Randwick Municipal Council, Randwick: A Social History, University of NSW Press, Sydney, 1985

Notes

[1] Botany Bay National Park Plan of Management, NSW National Parks and Wildlife, 2002

[2] 'Aborigines Celebrate Their Survival of White Settlement', The Age, 27 January 1993, p 10

[3] Arthur Phillip, 'Sydney Cove Selected by Phillip, 1788', in Manning Clark, Select Documents in Australian History 1788–1850, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1977

[4] Tim Flannery, 'The Sandstone City', in Tim Flannery (ed), The Birth of Sydney, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 1999

[5] Frances Pollon, The Book of Sydney Suburbs, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1988, p 148

[6] Botany Bay National Park Plan of Management, NSW National Parks and Wildlife, 2002

[7] Botany Bay National Park Plan of Management, NSW National Parks and Wildlife, 2002

[8] Randwick Municipal Council, Randwick: A Social History, University of NSW Press, Sydney, 1985

[9] Maria Nugent, 'Revisiting La Perouse: A Post-Colonial History', PhD thesis, University of Technology, Sydney, 2000

[10] La Perouse: The Place, the People and the Sea: a collection of writing by members of the Aboriginal community, Aboriginal Studies Press for the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1988

[11] Heather Goodall, Invasion to Embassy: Land in Aboriginal Politics in New South Wales, 1770–1972, Allen and Unwin in association with Black Books, NSW, 1996, pp 88–89

[12] Maria Nugent, 'Revisiting La Perouse: A Post-Colonial History', PhD thesis, University of Technology, Sydney, 2000

[13] Randwick Municipal Council, Randwick: A Social History, University of NSW Press, Sydney, 1985

[14] JH Bell, 'The La Perouse Aborigines', PhD thesis, Sydney University, 1959

[15] Iris Williams, 'Emma Jane Foster', in La Perouse: The Place, the People and the Sea: a collection of writing by members of the Aboriginal community, Aboriginal Studies Press for the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1988

[16] Maria Nugent, 'Revisiting La Perouse: A Post-Colonial History', PhD thesis, University of Technology, Sydney, 2000

[17] Maria Nugent, 'Revisiting La Perouse: A Post-Colonial History', PhD thesis, University of Technology, Sydney, 2000

[18] The Canns of La Perouse, http://cannsoflaperouse.blogspot.com.au/, viewed 11 December 2014

[19] Randwick Municipal Council, Randwick: A Social History, University of NSW Press, Sydney, 1985

[20] Beryl Beller, 'Shellwork', in La Perouse: The Place, the People and the Sea: a collection of writing by members of the Aboriginal community, Aboriginal Studies Press for the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1988

[21] Heather Goodall, Invasion to Embassy: Land in Aboriginal Politics in New South Wales, 1770–1972, Allen and Unwin in association with Black Books, NSW, 1996

[22] 'La Perouse Aborigines protest against removal', Sydney Morning Herald, 1928

[23] Heather Goodall, Invasion to Embassy: Land in Aboriginal Politics in New South Wales, 1770–1972, Allen and Unwin in association with Black Books, NSW, 1996

[24] Bain Atwood and Andrew Markus (eds), The Struggle for Aboriginal Rights: A Documentary History, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1999

[25] JH Bell, 'The La Perouse Aborigines', PhD thesis, Sydney University, 1959

[26] Maria Nugent, 'Revisiting La Perouse: A Post-Colonial History', PhD thesis, University of Technology, Sydney, 2000

[27] ABC Radio National, 'Happy Valley Revisited', 17 June 2007

[28] JH Bell, 'Some Demographic and Cultural Characteristics of La Perouse Aborigines', Mankind, June 1961

[29] ABC Radio National, 'Happy Valley Revisited', 17 June 2007

[30] ABC Radio National, 'Happy Valley Revisited', 17 June 2007

[31] Maria Nugent, 'Revisiting La Perouse: A Post-Colonial History', PhD thesis, University of Technology, Sydney, 2000

[32] 'La Perouse – then and now', Proud Heritage DVD, located at Tranby Aboriginal College, Sydney

[33] Maria Nugent, 'Revisiting La Perouse: A Post-Colonial History', PhD thesis, University of Technology, Sydney, 2000

[34] Maria Nugent, 'Revisiting La Perouse: A Post-Colonial History', PhD thesis, University of Technology, Sydney, 2000

[35] JH Bell, 'The La Perouse Aborigines', PhD thesis, Sydney University, 1959

[36] Letter to Jack Horner, 13 May 1964, Aboriginal-Australian Fellowship files, 1856–1978, State Library of NSW, Mitchell Library, 4057/12

[37] La Perouse Land Claim, located at Tranby Aboriginal College

[38] Kelrick Martin, 'The Survival Day Concert 2001', 26 January 2001, http://www.abc.net.au/message/blackarts/culture/s660896.htm

[39] Patricia Karvelas, 'Deal does nothing to revive dying black community', The Australian, 5 September 2005

[40] Botany Bay National Park Plan of Management, NSW National Parks and Wildlife, 2002

.