The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Industry in the Cooks River valley

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Industry in the Cooks River valley

Development

It was only a matter of time before various potential uses for the Cooks River valley were discovered. While the valley had minor agricultural or pastoral potential, housing the growing population of Sydney Town required timber and stone, bricks, mortar and clay. The valley had these in abundance and some of the local timbers were seen as a useful export, particularly hardwoods that could be used by the British navy.

Once an industrial base had been established, over the nineteenth century these initial industries expanded and new ones appeared, reflecting the development of Sydney as an important and expanding manufacturing base.

Timber and lime

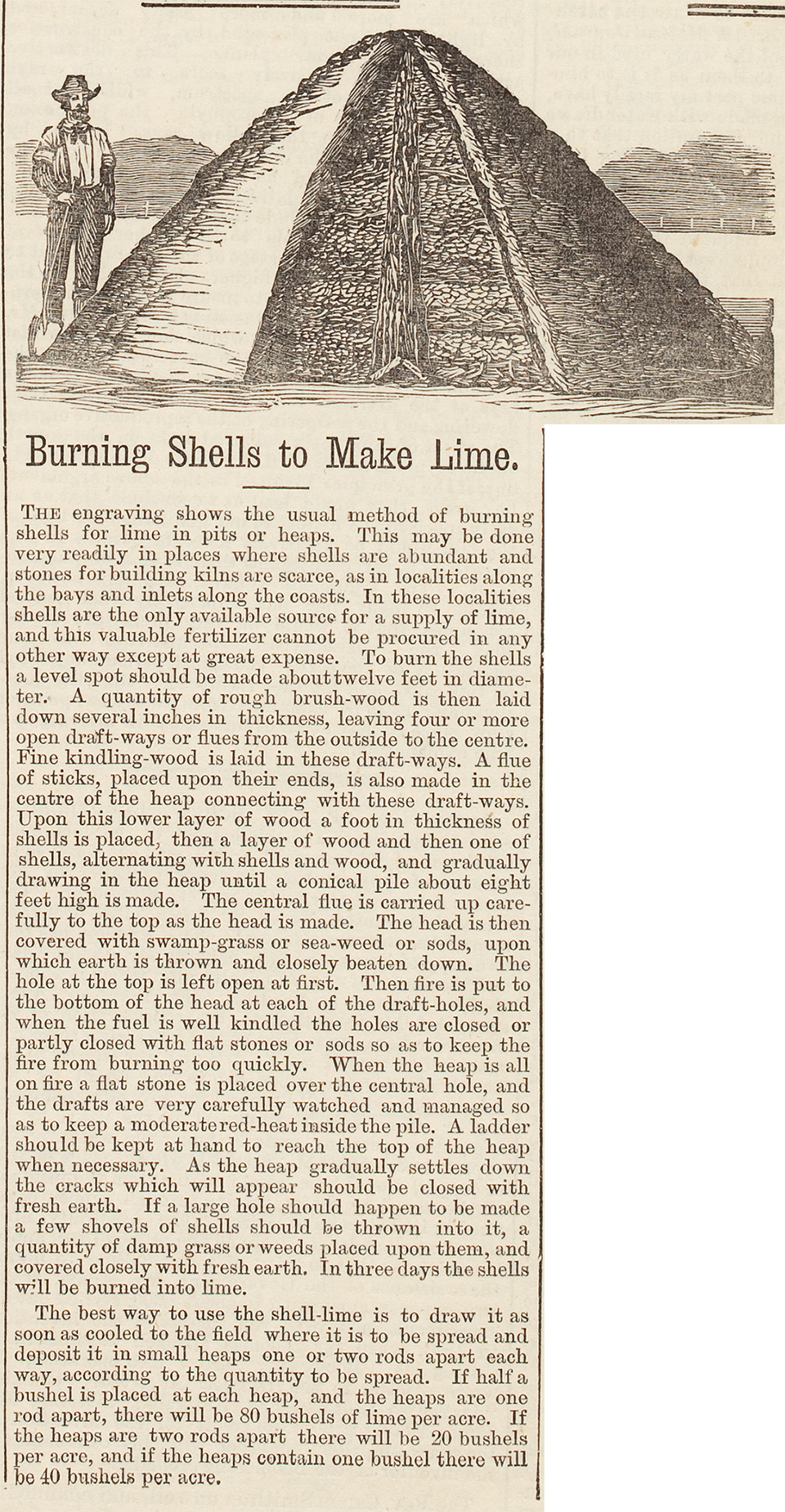

Sydney [media]had no natural limestone to make mortar for building so improvisation was necessary. The substantial middens in Botany Bay and along the Cooks River were a resource that could be burned to make lime and this became one of the earliest industries of the region, recorded from before the 1828 census. The shells, mostly Sydney cockle and Sydney rock oyster, were reduced to lime by alternating layers of brush timber and shells in a conical kiln, starting fires in the airways and then sealing the kiln for three days to retain the heat. [media]A photograph of the Cooks River dam shows a limekiln beside the road on the north bank. [1]

After 1803, the valley was considered a good source of timber, both for Sydney and for export to Britain for the use of the Royal Navy. Ironbark and turpentine from the ridges provided good building material and casuarina trees from the riverbanks could be split into durable roofing shingles.

Quarries

Pipeclay deposits found in the Cooks River clay plain area were turned into pipes and tiles in localities from today's Campsie to Punchbowl after 1810.

Sandstone outcrops along the river were quarried for building stone from at least the 1830s. The sandstone used for the Cooks River dam in 1838–40 was almost certainly quarried locally on both sides of the river; the Canterbury Sugarworks was built from stone quarried in today's Hurlstone Park, as was the church and schoolhouse of St Paul's, Canterbury. By the 1870s, demand for sandstone to construct mansions along the railway line from Stanmore to Redmire (Strathfield) was so high that a quarry was opened on the south side of the river overlooking Cup and Saucer Creek. The stone from this river street quarry was considered to be particularly high quality and it was used by the government architect in the construction of the Old Medical School at the University of Sydney, as well as for less exalted uses such as house footings, kerbs and the edges of Canterbury's municipal gardens.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Schwebel family had quarries in Marrickville and Undercliffe, on each side of the river, and William Jackson opened a quarry above Wolli Creek. The street of six stone cottages he built for his family, Jackson Place, is an important site in the heritage of the area. [2]

Fulling mills

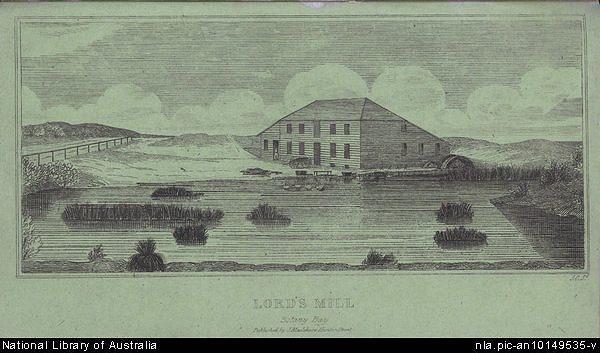

Simeon Lord, on 21 October 1815, [media]announced in The Sydney Gazette that he had built a fulling mill on the creek flowing into Botany Bay. The actual location was near the later Botany waterworks, between Botany Road and the bay. The 1823 land grant of 600 acres (243 hectares) to Lord included much of the water reserve and Lord's mill was on the Mascot side of the millstream. 'A commodious house' was built, as well as cottages for his workmen.

Sugarworks

[media]Built for the Australian Sugar Company as a sugar refinery, work began on the Canterbury Sugarworks in late 1840 and it opened in September 1842. Scottish stonemasons used local sandstone and ironbark timber to construct the building and the Cooks River was dammed to provide fresh water for boilers. Raw sugar was imported from overseas and brought by cart from Sydney to Canterbury for processing into white sugar and molasses (the story that sugar was brought up the river by barge is without foundation). Though extremely efficient, the Sugarworks closed in 1854 in a labour shortage caused by the gold rush. The company was re-formed as the Colonial Sugar Refining Co and it concentrated its operations closer to the city where one of the managers, Ralph Mayer Robey, had opened a second factory.

Woolwashing

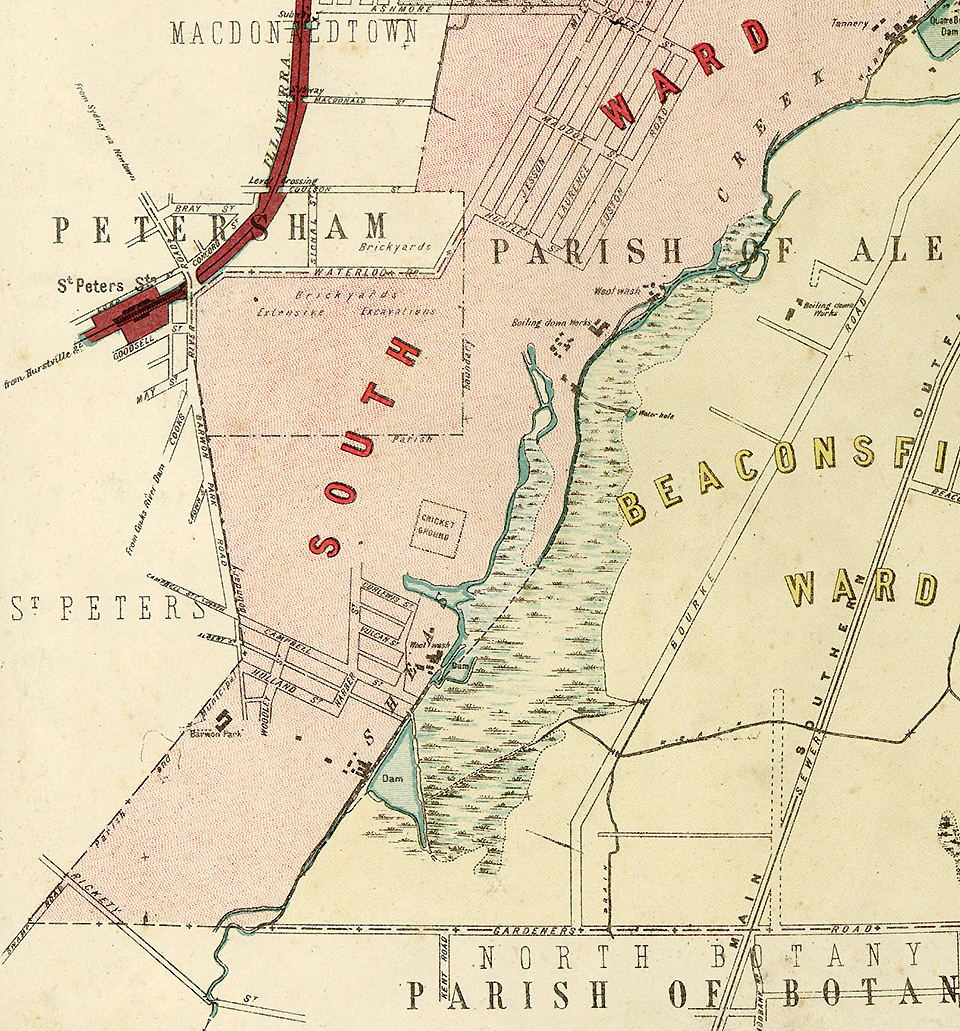

[media]The presence of the Sugarworks dam encouraged other industry to the area around the junction of the Cooks River and Cup and Saucer Creek. In 1863, Samuel Lucas opened a primitive woolwash on the western bank of the creek, using the strong flow of water over the rocky falls to remove the grease from the wool in the final cleansing operation. Frederick Clissold, a fellmonger from the upper reaches of Sheas Creek on the Waterloo estate, set up a more elaborate woolwash on the eastern bank of the creek, opening in 1868. Wool prices were at their highest and these industries took advantage of the boom. By July that year, an unpleasant 'greasy scum' was beginning to collect around the stonework of the dam at Tempe and the Cooks River's water became so polluted that the fish and prawns 'for which it was most celebrated' [3] were no longer to be found.

Once the price of wool began to fall in the 1870s, the Cup and Saucer Creek site was briefly used for a gold stamping works, crushing tailings from the Tambaroora goldfield. This industry failed in less than a year, probably because the site was too far from rail transport. In the meantime, William Mayne set himself up in Lucas's old woolwash buildings, boiling down horses and cattle that had died of disease or old age. The creek provided a reliable water supply and a bacon curing factory and slaughterhouse also began operations along its banks, while Clissold's land became the location for a very successful tannery with 26 tan pits, six lime pits and surface drainage. The continued use of the Lachlan and Botany swamps for Sydney's water supply diverted new industries of the 1870s elsewhere. Several slaughterhouses, woolwashes and boiling-down establishments were located on the Arncliffe and Wincanton estates beside Wolli Creek where the waste added itself to the sludge from the Cooks River, slowly backing up behind the dam at Tempe.

Brickworks

The real estate boom of the 1880s encouraged the opening of many small brickworks to exploit the clays in the Cooks River catchment. In Marrickville, Hurlstone Park, Campsie, and along the river at Croydon Park and Enfield, brickworks accompanied the spread of suburban housing. At the head of the Cooks River, the Enfield Brick Company operated from 1903 to 1905, on a site later to become Enfield Marshalling Yards, [4] the Strathfield and Enfield Steam Brick Works opened up in Water Street and the Western Suburbs Brick and Tile Company was located in Dean Street. The Dean Street brickworks was later redeveloped into Dunlop Street industrial precinct in the late 1950s. [5]

[media]In the meantime, Owen Blacket and partners bought the Sugarworks building as a heavy engineering factory in anticipation of a railway being constructed along the northern bank of the Cooks River. The enterprise failed when the railway did not materialise and eventually the building became a bacon processing works, first owned by Denham's Refrigeration, and later by J C Hutton Pty Ltd. This industry lasted until 1982.

Mascot airfield

Nigel Borland Love, an aviator with [media]the Australian Flying Corps in World War I, and another Australian airman, WJ Warneford, joined HE Broadsmith, chief designer for the aircraft manufacturers A V Roe & Co Ltd, who had secured the Australian agency for the Avro company. When he returned to Sydney after the war in June 1919, Love searched for a suitable airfield and eventually leased a grazing paddock near the Cooks River at Mascot, which proved to be ideal.

The partners, registered as the Australian Aircraft & Engineering Co Ltd with Love as managing director, began to assemble Avro 504K aircraft at Mascot in February 1920. While Broadsmith worked on the aircraft, Love tried to raise money and create interest in aviation by joy flights and charter operations including flights over Sydney for photographic purposes and piloting the first fare-paying passenger from Sydney to Melbourne. The company supplied Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Services Ltd with its first passenger commercial aircraft. However, lack of orders, expenditure in designing and developing a five-seat commercial aircraft and failure to gain assistance from the Commonwealth government forced the company into voluntary liquidation in 1923. When their lease expired the Commonwealth resumed the airfield, now Kingsford Smith Airport. [6]

Flourmill

NB Love married the daughter of a flour miller and in 1935 opened a flourmill in Braidwood Avenue, Enfield, west of the Cooks River bridge over Liverpool Road. In 1952 he set up Millmaster Feeds Pty Ltd to produce stock feed pellets at Enfield, introducing a high-speed dough development technique and also manufacturing gluten and starch. Weston Milling acquired the mill in 1962.

Enfield Marshalling Yard

In the twentieth century, the Enfield Marshalling Yard was the largest industrial development in the Cooks River valley. It was developed in 1916 on Enfield Council's proposed Enfield park site at the head of the river, which was resumed by the State Government. The yard's location was an important terminus in the Metropolitan Goods Line rail network, proposed in 1908–10. In subsequent years, the large marshalling yard at Enfield became the lynchpin of the State's rail freight system and provided employment to many local residents.

Within the marshalling yard was a tarpaulin factory that operated from 1925 until 1991. At its peak in wartime, there were 81 employees. Tarpaulins made in this shed had a variety of uses including cover for the loaded wagons, tool covers, leggings and other railway-related items. The factory and its associated fireproof store comprises two nineteenth century prefabricated cast and wrought iron single bay buildings that were once in the Sydney yard near Central Station. Based on its heritage assessment, the item is considered to be of State significance. [7]

Industrial pollution

By the late 1860s, as a result of the industrial development along the river, the polluted state of the Cooks River had become a talking point. Complaints, particularly about the woolwash, were published in The Sydney Morning Herald:

…There was a very perceptible odour of the kind usually met with in the vicinity of woolwashing establishments. This appeared to be caused by the accumulation of refuse matter among the herbage on the banks of the river at points where the bends of the stream, and its ordinary flow, favoured such accumulations. These evidences of pollution were as strong, at intervals, in the lower portion of the river as near to the establishment in question. Above the small dam the river was literally covered with scum for some distance, and had a most filthy appearance…Already has much injury been done by the destruction of the fish, and by the pollution of the river to such an extent as to render it unfit for bathing purposes. Already are those who reside in its vicinity annoyed, and the value of their properties diminished. These injuries and annoyances must increase, the public health must be endangered, and the value of property near the river must be still more seriously diminished, unless the nuisance complained of be effectually and permanently abated. [8]

As a result of these complaints, Frederick Clissold and his partner George Hill 'set themselves earnestly to work to remedy the evil complained of, and all the water used on their establishment…is now strained and filtered ere it is returned to the river'. [9]

The industrial site at Cup and Saucer Creek continued to contribute to the pollution of the river. By 1883, the Royal Commission on Noxious and Offensive Trades singled out Tebbutt's tannery and William Mayne's knacker yard for special mention in their report [10], as drainage from both went straight into the Cooks River unfiltered. Near the mouth of the river, Sheas Creek had also become a similar problem as noxious industries, banned from the Sydney water catchment, had located to the banks of the creeks in the Waterloo estate. In addition, Sydney's sewage was being dumped on the banks of the creek.

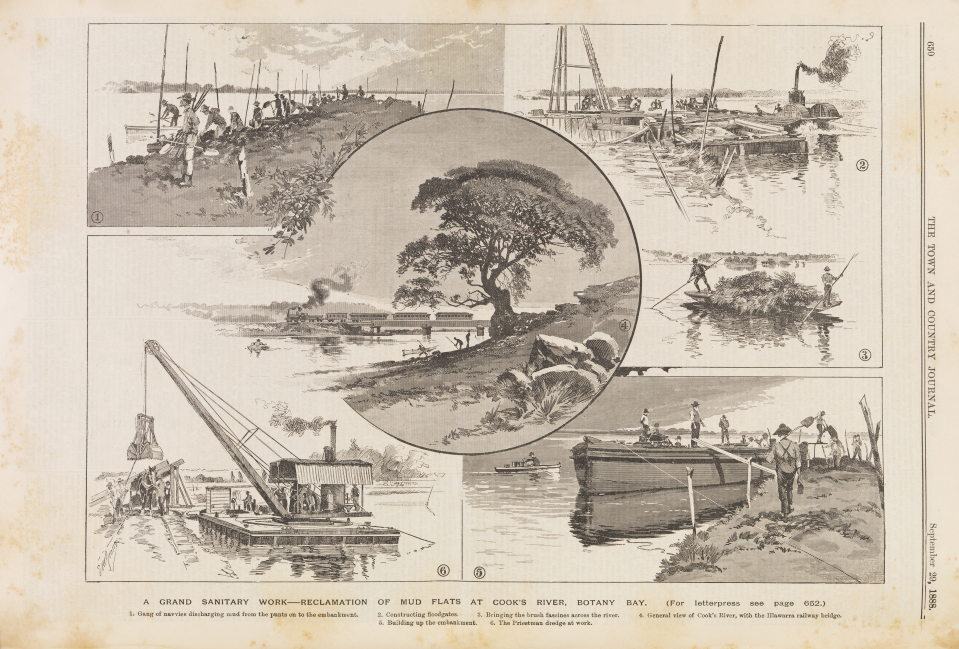

[media]In 1886, an idea first proposed by Thomas Holt in 1869 was partially implemented: Sheas Creek was dredged and confined within sandstone walls to form the Alexandra Canal, in an attempt to improve the flow of water and encourage barge transport. The government hoped that the new channel, constructed by unemployment relief labour, would provide a route for carrying coal from Botany Bay to the government railway workshops at Eveleigh, and that 'once the channel was completed the banks would be lined with manufactories'. [11] Very soon, new woolsheds were built along the canal with barges taking the wool down to Botany Bay. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, boiling-down works, tanneries and other noxious trades crowded into the area.

Flooding

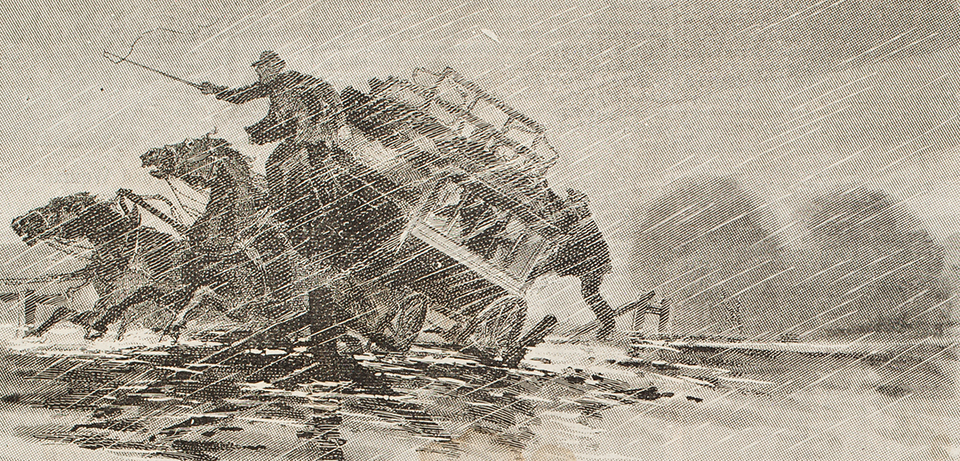

As well as being polluted, the Cooks River flooded every time there was a downpour. In April 1841, after a very rainy and windy night, A B Spark noted that 'the river has overflown the dam, and the whole of the lower ground is under water'. [12] On one spectacular weekend in May 1889, 17 inches (43.2 cms) of rain fell in one weekend and residents of the new Tramvale estate at Gumbramorra Swamp had to be rescued in rowing boats. [media]At Canterbury, the omnibus was swept off Prout's bridge by the raging river and the fare-boy and all the horses were drowned. Chinese market gardeners who cultivated the alluvial terraces all along the river's banks 'presented a most pitiable spectacle' [13] because their houses were completely flattened. All the creeks feeding the river became torrents: Cup and Saucer Creek was described as 'an insignificant and quiet feeder enough in summer, but in flood time, after heavy rains, a brawling little cataract'. [14]

Proposals to clean up the river

In 1896, an engineer, HB Henson, gave a paper to the Engineering Association of NSW [15] in which he made several drastic recommendations to clean up the river. He believed that, because the river meandered through flat land near its source, the streams that carried the runoff were not swift flowing enough to carry the silt out to sea. The Cooks River dam and weir not only prevented tidal flushing from the bay but also actively encouraged silt deposition making flooding worse in heavy rain. Stage one of his plan was the removal of both obstructions; stage two was the construction of a canal and tunnel from Parramatta River via Long Cove through Dulwich Hill and into the Cooks River. Water from the swifter-flowing Sydney Harbour would flush out the silt. Stage three, seen as being ultimately necessary, would join the two rivers by a second canal from Homebush Bay through Strathfield to the headwaters of the Cooks River at Chullora. The stage two canal would be large enough to take barge transport from the Alexandra Canal to the Sydney docks, saving freight distances and costs. No action was taken on the plan, apart from some desultory attempts at dredging.

Stormwater drainage

Concern about public health in the valley continued to grow as population moved into the surrounding suburbs. In 1897, the medical advisor to the Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board declared that, in areas where stormwater drains were constructed, the health of the population improved dramatically. Mortality from diarrhoea, diphtheria and typhoid fever all fell when 'foul creeks and ditches' were turned into 'clean concrete channels, with a proper fall, so that there is no stagnation of slop waters'. [16] At that time, local councils were also responsible for improving drainage but, in 1924, after the spectacular floods of 1922 had aroused public anger, the board became the sole constructing authority for stormwater drains.

The boom time for settlement of the valley was from 1895 to the end of the 1920s, and complaints from new residents grew about the silted and polluted state of the river. In 1925, the Cooks River Improvement League was formed. It published a booklet, Our Ocean to Ocean Opportunity, designed to arouse public anger, in which it demanded that the government take some action to clean up the river. It considered the main problems of the river to be 'obstructions, which prevented tidal flushing; siltation, caused by stormwater drainage; and pollution from sewage, sullage and trade wastes'. [17] A letter from the local member, Varney Parkes, who lived near the river in Canterbury, predicted that the watercourse would become a 'miasmatic morass' within 30 years if it continued to be ignored. [18]

On the upper reaches beyond Brighton Avenue Bridge, Campsie, to which a small tide still flows, and beyond which the river consists of a series of water holes, these ponds, about 40 years ago quite extensive in size, are now reduced to one-half their original capacity, and are fast completely filling up with mud and slime and the enormous growth of beds of rush and reed. All along the main salt water channel dense beds of rush and reed, thriving on the ever extending mud banks, are year by year reducing the width of the waterway. This filling-in is caused by hundreds of street water tablings and drains running down the slopes into the channel – carrying soil and organic matter in abundance – aided by the solid dam blocking the watercourse at Tempe. The seriousness of the question, besides the destroying of a pretty serpentine watercourse, lies in the fact that in some 30 years or much less this channel will become, by filling up, nought but a miasmatic morass, overspreading the flat lands, which are fairly extensive on the river banks. The conditions now are dangerous to public health – and what will these conditions become as years roll on – and it should be borne in mind that the population now living on the river slopes is very great, numbering about 300,000 souls.

[media]The government's response in 1928 was to approve the expenditure of £94,000 to dredge the river up to Burwood Road, Campsie and to remove obstructions at Tempe and at the Sugarworks dam. The greatest expansion of the stormwater drainage system took place during the Depression, as the Prevention and Relief of Unemployment Act of 1930, followed by the Metropolitan Water, Sewerage, and Drainage (Amendment) Act in 1935, allowed many new works and extensions to be built. It was during this era that the Cox's Creek and upper the Cooks River canals were created, as well as the Cup and Saucer Creek, Marrickville and Muddy Creek storm water canal systems. The work was not completed until 1947.

[media]In 1946, the Cooks River Improvement Act was passed, its primary aim being to control flows and prevent degradation of the banks. It gave control of the lower reaches of the Cooks River (from Tempe to Canterbury Road) to the NSW Department of Public Works for flood mitigation and river diversion works. The river was dredged, 'swamps' were reclaimed and the banks of the lower river were strengthened with iron sheet piling. These works reduced dry weather flow but conversely, during wet weather, they caused major flood damage. 'The solutions chosen for the river's problems were engineering ones which had the effect of providing a more efficient stormwater drain for the urbanised Cooks River Valley'. [19]

[media]Between 1947 and 1955, the Alexandra Canal and lower reaches of the river were diverted 1.6 kilometres west of the natural outlet to allow for the reclamation of the large mangrove and saltmarsh basin at the mouth of the Cooks River to enlarge Sydney Airport. This area had been relatively isolated from development and the tidal flats 'were the summer home of great numbers of migrating waders, from their far northern breeding grounds'. [20] The works 'embraced old works and landmarks closely associated with the early history of Sydney's water supply and sewerage, including the pump-house and adjacent supply ponds for the Botany Swamps water supply, and the sites of the one-time Botany and Rockdale sewage farms'. [21] Despite best efforts, by the end of the 1960s there was little improvement in the river. Regular chemical spills from factories in the area took place, as well as illegal dumping, and large fish kills resulted. Factory pollutants were precipitated out when they met the saline waters of the estuary and the result was that the sediment at the bottom of the river contained higher concentrations of toxins than the water itself.

[media]In 1975, the Cooks River and its estuaries were classified under the Clean Waters Act 1970 No 78 by the State Pollution Control Commission as 'restricted', that is, unsuitable for domestic purposes but suitable to maintain aquatic life and associated wildlife. This classification was given to control industry and domestic outflows into the river.

References

Alexander Brodie Spark diaries, 1 January 1836–22 September 1856, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales A4869

Judy Finlason, The Place That Jackson Built: The Story Behind Six Stone Cottages, Wolli Creek Preservation Society, 1999

Noxious and Offensive Trades Inquiry Commission, Report of the Royal Commission, appointed on the 20th November, 1882, to Inquire into the Nature and Operations of, and to Classify Noxious and Offensive Trades, Within the City of Sydney and its Suburbs, and to Report Generally on Such Trades, together with the minutes of evidence and appendices, New South Wales Legislative Assembly, Sydney, 1883

WV Aird, The Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage of Sydney, Sydney, Metropolitan Water Sewerage and Drainage Board, 1961

Notes

[1] Limekiln, Cooks River Dam, N.S.W, ca 1870s, cabinet card photograph, 10.9 x 16.6 cm, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, SPF/634

[2] Judy Finlason, The Place That Jackson Built: The Story Behind Six Stone Cottages, Wolli Creek Preservation Society, 1999

[3] Report by Charles St Julian of Marrickville Council, The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 June 1868

[4] Graham Brooks and Associates, Proposed Intermodal Logistics Centre, Enfield Assessment of Heritage Impact, Sydney Ports Corporation, 2005

[5] Cathy Jones, 'Industry and Commerce', Strathfield Heritage website, http://strathfieldheritage.org/industry-commerce, accessed 13 February, 2007

[6] 'Nigel Borland Love', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/love-nigel-borland-7244; Tropman and Tropman, Statement of Significance, Tarpaulin Factory and Associated Buildings, NSW Heritage Office, 2005

[7] Tropman and Tropman, Statement of Significance, Tarpaulin Factory and Associated Buildings, NSW Heritage Office, 2005

[8] Report from Charles St Julian, Marrickville, The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 June 1868

[9] The Sydney Morning Herald, 21 August 1868

[10] Noxious and Offensive Trades Inquiry Commission, Report of the Royal Commission, appointed on the 20th November, 1882, to Inquire into the Nature and Operations of, and to Classify Noxious and Offensive Trades, Within the City of Sydney and its Suburbs, and to Report Generally on Such Trades, together with the minutes of evidence and appendices, New South Wales Legislative Assembly, Sydney, 1883

[11] The Sydney Morning Herald, 1 October 1888

[12] AB Spark, 29–30 April 1841 in Alexander Brodie Spark diaries, 1 January 1836–22 September 1856, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales A4869

[13] Illustrated Sydney News, 6 June 1889

[14] RB Parry, 'Canterbury: An Old Sydney Suburb, Interesting Reminiscences', Evening News, 14 November 1908, p 13

[15] HB Henson 'Cook's River: Its Condition and its Destiny', Minutes and Proceedings of the Engineering Association of NSW, vol xiv, 1895–96

[16] WV Aird, The Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage of Sydney, Sydney, Metropolitan Water Sewerage and Drainage Board, 1961, p 204

[17] Cooks River Project, Cooks River Environment Survey and Landscape Design, Chippendale, 1976

[18] Varney Parkes, Letter to the Editor, The Sydney Morning Herald, 11 March 1925

[19] Cooks River Project, Cooks River Environment Survey and Landscape Design, Chippendale, 1976

[20] Arnold McGill, quoted in Cooks River Project, Cooks River Environment Survey and Landscape Design, Chippendale, 1976

[21] WV Aird, The Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage of Sydney, Sydney, Metropolitan Water Sewerage and Drainage Board, 1961, p 198

.