The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Holsworthy Internment Camp during World War I

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Holsworthy Internment Camp during World War I

[media]Before the beginning of the World War I, the Australia Defence Forces acquired 80,000 acres (approximately 32,375 hectares) of land at Holsworthy. [1] When the Commonwealth Government assented to the War Precautions Act in 1914, it was decided that people who were of German origin or descent, as well as those from countries allied with Germany, might be a security risk, and so places had to be found to detain them.

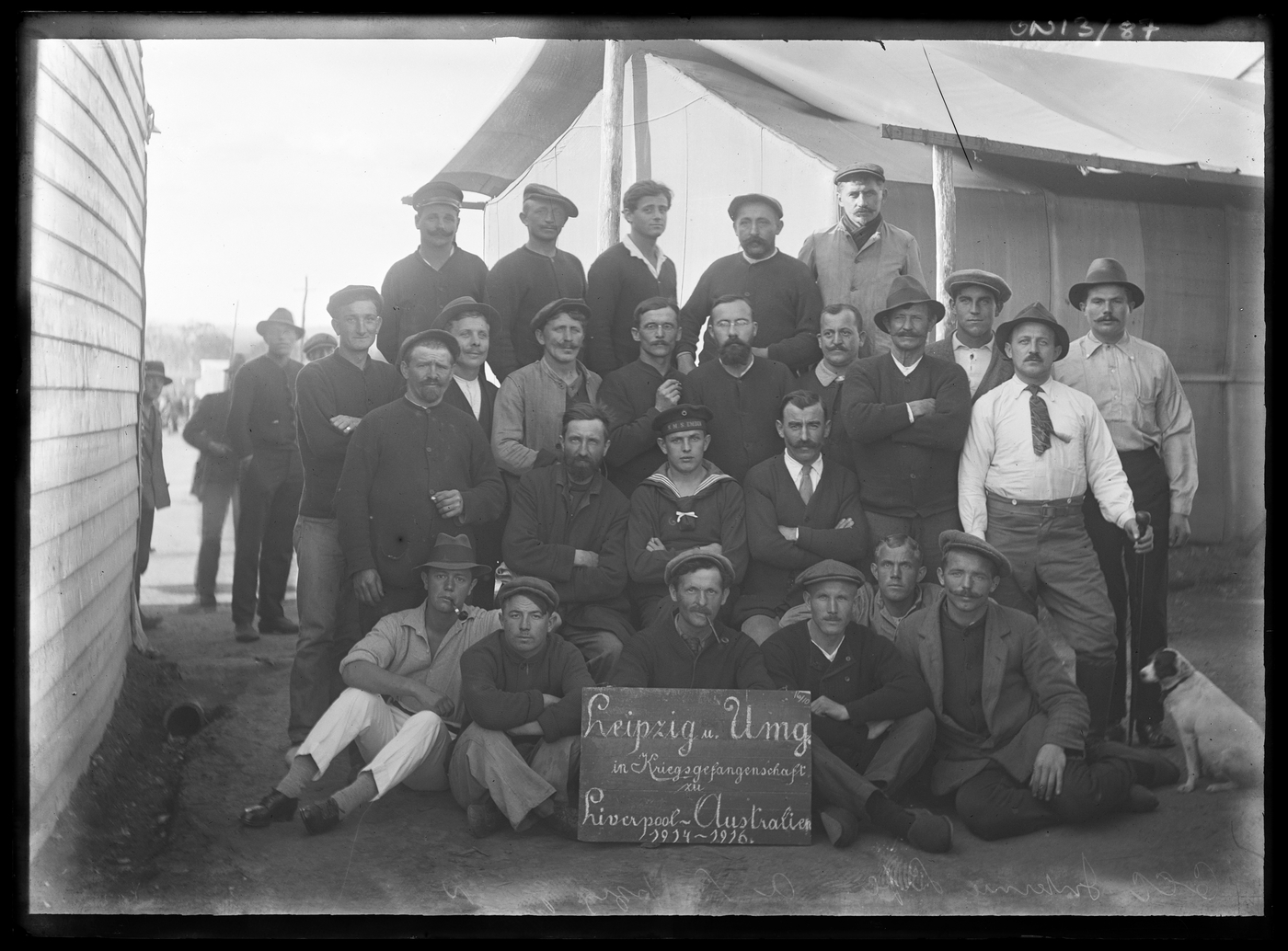

At first people were detained in army barracks or training camps but the government soon realised they would need more permanent accommodation and set up camps in specific locations, one of these being the German Concentration Camp at Holsworthy in the Liverpool district. [2] As early as September 1914 about 100 seamen who had been taken from German and English ships arrived at the camp. Others soon followed from various locations.

On 24 February 1915, the British Government sent a cablegram to the secretary of state for the colonies, asking Australia to take German subjects who were imprisoned in straits settlements. On 5 March the governor-general sent a cable back to London stating Australia's willingness to do this. During 1915 and 1916, Australia was asked to take prisoners from Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Hong Kong, Borneo and Fiji, as well as the two batches of prisoners who arrived from Singapore in April and May 1915. [3] This, according to Gerhard Fischer, was the beginning of a new form of transportation, resembling that of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries with the British Government effectively sending unwanted prisoners to Australia just as it had done at the earlier time. [4]

[media]People were sent to Australia for a variety of reasons. German citizens were the most obvious candidates for internment; they might have been company representatives or in Australia for business reasons. Also interned were men who were naturalised Australian citizens, and even in some cases, native born Australians of German descent. As well as Germans, there were men from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, of whom the majority were Slavic, mostly from Dalmatia, as well as a few Czechoslovakians and Hungarians. One of the Dalmatian internees was a sixteen year old, named Anthony Splivalo, who had been living in Perth since January 1911. Much of what we know of the camp comes from his book, The Home Fires, which was written in 1982 in Canada, where he settled after his release. [5]

Camp life

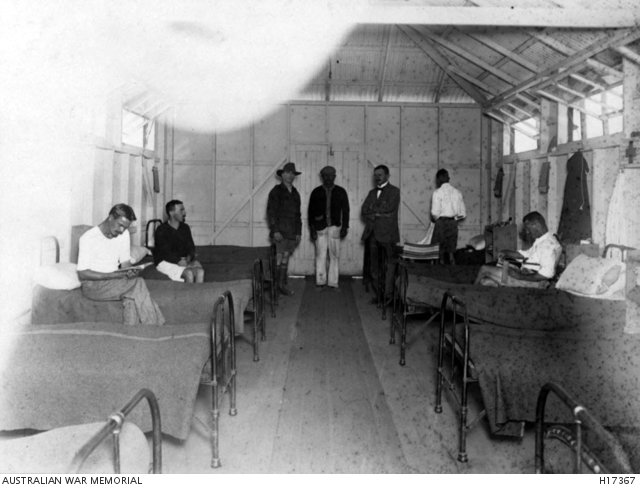

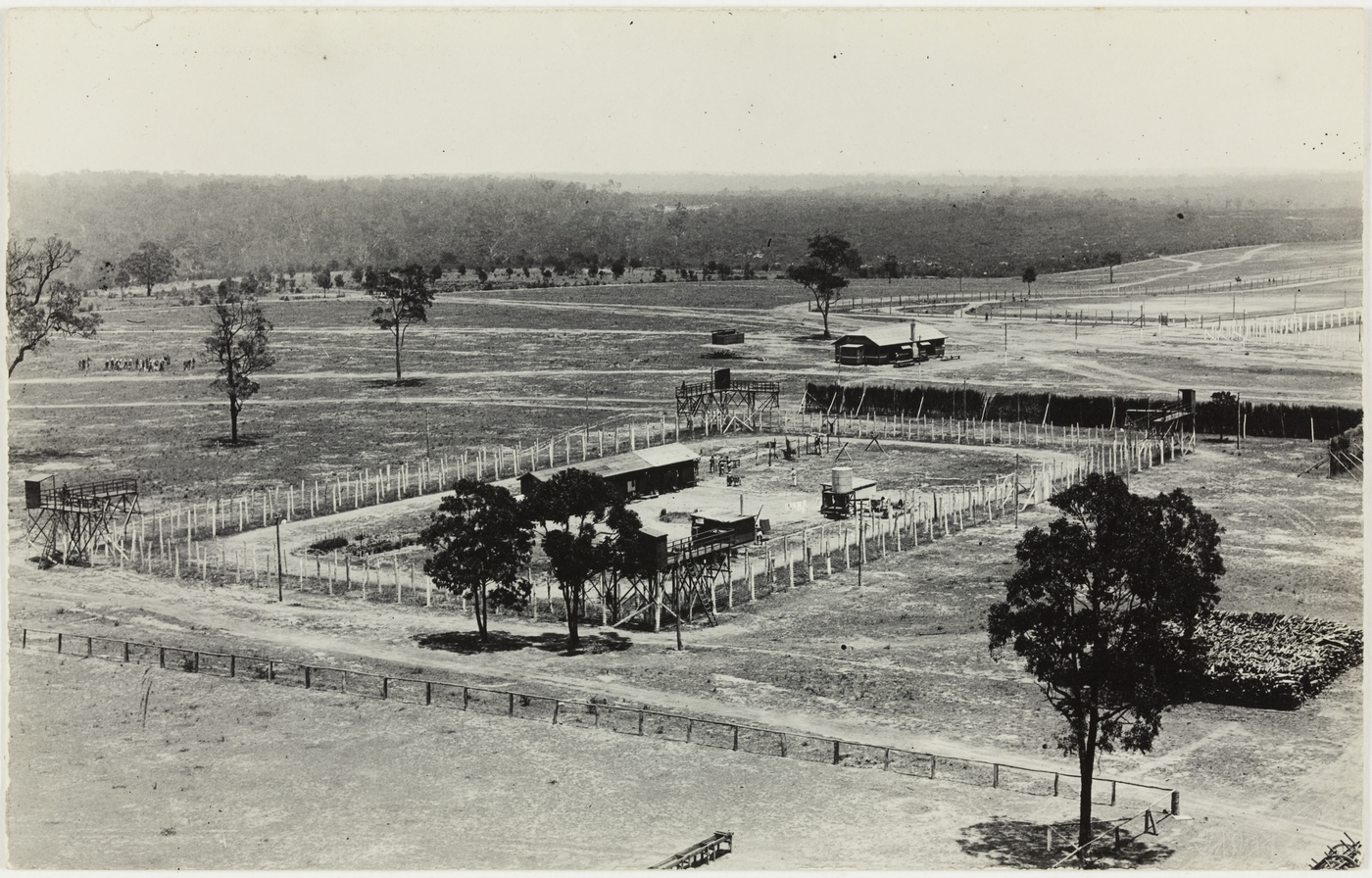

When the first internees arrived at Holsworthy, the camp consisted of a large group of tents in an open area, which later became the Light Horse Regiment's camp. Barracks later replaced the tents to house the approximately 6,000 men interned there. [6] Initially these were not furnished and the men had to buy something to sleep on, while many built beds from saplings found in the nearby bush. The men could buy hessian and straw for mattresses. Blankets were supplied but there were not usually enough of these. [7] Anthony Splivalo described the section where he lived as having a heavy canvas awning for each mess. This was fastened at night with rope and stretched out on two long poles during hot or wet days. His group of five men built two double bunks which were placed along the sides of their area and a single bunk along the back wall. This gave them a 'social space' where they placed table and chairs they had made themselves. [8]

[media]There was a hospital in the camp, which varied in size from time to time. By April 1917 it consisted of four large rooms with sixteen beds in each as well as several tents for patients with infectious diseases. By November 1918 there were five wards, each 33 feet (approximately 11 metres) by 18 feet (6 metres) and 12 feet (4 metres) high. Four were for general cases and one was a surgical ward. [9]

Cooking was not allowed in the barracks and kitchens were set up to feed the men. These also varied but those described by Splivalo were 'two cavernous kitchens' which were set up near the latrines so flies tended to be a problem. [10] A bake house was built by September 1918 but was declared by to be a fire hazard because of the small clearance between the chimney and the ceiling boards. [11]

There were ablution blocks and latrines at set places within the camp, as washing was not allowed in the barracks, but these were generally considered not adequate for the needs of the men. Godden MacKay states that by May 1916 there were six hot and twenty cold shower baths as well as 48 tubs for washing but they were not in a building or under cover. [12] The situation had not improved greatly by 1918. Not much is known of the laundry facilities but Splivalo referred to it as a combined laundry and ablutions block. [13]

Dust and mud could be a problem in the camp, depending upon the weather conditions. The streets between the barracks were 10 feet (three metres) wide and every fourth street was ( 33 feet (seven metres) wide. It was noted in 1916 that these and other open areas were not lit at night, making gutters and unfenced excavations dangerous. [14]

By the time Anthony Splivalo came to the camp there appears to have been a thick barbed wire fence which he described as being one a 'mouse could not get through'. [15] There was an observation tower outside the fence, initially made of wood with a guardhouse on top, but this was eventually replaced by a steel structure. There was also a searchlight at night and a machine gun, which could be used if needed. [16]

[media]Visits by family were restricted to wives and children but not fiancées who were excluded from this provision. Originally visits were for only 15 minutes per month and, on occasion, with the prisoners behind fences. One arrangement had the men separated from their visitors by barbed wire and a corridor, but this did not last long. [17] After bitter complaints, visits were extended and the men could meet their families at a designated spot outside the camp with guards watching. A prison, known as Sing Sing, was set up for internees who tried to escape or who committed crimes while in the camp. [18]

Labour

When the camp was first set up, men were set to clearing land in four hour shifts. However, this was considered beneath the dignity of many of the men. After a general strike in 1915, compulsory labour was replaced by voluntary work. Internees worked in two shifts of 1,000 men, with 500 working in the morning and 500 in the afternoon. At the end of two weeks these were replaced with another thousand men. There was also some specialised work available for ships' carpenters who could make anything from furniture to buildings. Other specialised workers included stable hands, cooks, canteen workers and when the shops were built there would have presumably been paid work in them.

By May 1917 there were still between 750 and 800 workers building roads and clearing the bush, working a seven-day week. When the construction of the railway from Liverpool to the main camp was begun in February 1917, some internees worked on building part of this until it was completed in January 1918. Many of the prisoners still considered the work beneath them. The 'well conducted' could grow vegetables and sell these for income. [19]

Social activities

Initially there was little for the prisoners to do at the camp, and they soon organised activities that eventually turned the camp into a thriving small town, albeit behind barbed wire. As early as November 1914 the Deutsches Theatre Liverpool had been formed, with the first performance being in a tent. However, the internees soon received permission to build a theatre, which was opened in June 1915.

Activities such as art classes, bands and acting groups were formed but these soon became much more than just something to do to fill in time. The bands soon became orchestras, which performed on a regular basis for the camp and later for the people of Liverpool. The acting soon became a professional group, with men playing women's parts very effectively and costumes created for the actors. Soon there were four theatres as well as an open-air free picture theatre, four detached schoolrooms and a small shopping centre. These amenities were designed and built by the internees themselves, with the permission of the camp authorities.

Some prisoners did have their own private wealth, which was confiscated by the Government, but they were allowed to have money for their personal needs. [20] Others worked in paying positions within the camp, while the more entrepreneurial among the internees set up shops. By September 1918 there were butchers' shops, fruit shops, nine cafes and restaurants. There was also a pawnshop selling used clothes and later new garments, as well as a leather works, a book bindery, cigar stands and lending libraries. [21]

In contrast, the life of the guards was not as good as that of the prisoners. Guards were usually men deemed unfit for active service, something that was not really compatible with the job, which involved being on their feet for extended periods of time, just watching the prisoners. This was generally a very boring occupation and the number of men whose crime was going absent without leave (AWOL) was high. [22]

Release

In May 1919 the Willochra arrived in Sydney from New Zealand where the influenza epidemic had already taken hold. One hundred and four men were sent straight to Holsworthy and on 27 May the ship left with 665 men from the camp. Other men were transported in and out of the camp. By 20 June, hundreds of men had become infected and by 19 July, when the last man died, 94 men had died out of a population of 4,000. [23] Men continued to be released, with the last man leaving the camp on 5 May 1920. Most were deported. [24]

Opinions as to what life in the camps was like was varied and tended to be very subjective. The author, while involved in setting up an exhibition about the camp, gained the impression that, if it had not been for the attitude of the prisoners, who made the most of their circumstances and used their skills and interests to relieve the boredom and create a life behind barbed wire for themselves, life would have been very different and the loneliness caused by separation from their families would possibly have been overwhelming, causing more suicides and cases of insanity than those that occurred during the up to six years of imprisonment.

Others see it differently, more a life of privileged and not what prison should be. Frank Doak's article, 'The Good Life' states:

The end of World War I must have been received with trepidation by some inmates of Australian Concentration Camps. For them the end of hostilities also brought an end to an almost idyllic lifestyle. And for others an end to lucrative business enterprises. [25]

Doak goes on to speak of the inmates' opportunities to run their own shops and cafes and the 'almost nightly' orchestral concerts and stage shows, He states that nowhere in the world could prisoners have had such a comfortable lifestyle.

While on the face of it, this might seem true, it ignores the fact that the inmates were behind barbed wire and without freedom. One could argue that 'nowhere in the world' would prisoners have acted with such enterprise that they were able to have these 'shops and cafes' and the 'almost nightly' orchestral concerts and shows that were all organised and run by inmates. This degree of enterprise says a lot about the spirit of the German people and what they could achieve in such a short time.

References

Gerhard Fischer, 'Botany Bay Revisited: The Transportation of Prisoners of War and Civilian Internees to Australia During the First World War, Journal of the Australian War Memorial, no 5, October 1984

Don Godden, Beverley Johnson, Matthew Kelly and Dominic Steele, 'Archival Recordings', First Field Hospital Site, Holsworthy, vol II, Godden Mackay, Sydney, 1995

Anthony Splivalo, The Home Fires, Fremantle Arts Centre Press, Fremantle, WA, 1982

Notes

[1] Sometimes spelt 'Holdsworthy'.

[2] At this time the name 'concentration camp' simply meant concentrating people into one space. It wasn't until World War II that it gained the connotations we associate with it today

[3] Gerhard Fischer, 'Botany Bay Revisited: The Transportation of Prisoners of War and Civilian Internees to Australia During the First World War, Journal of the Australian War Memorial, no 5, October 1984, pp 36–37

[4] Gerhard Fischer, 'Botany Bay Revisited: The Transportation of Prisoners of War and Civilian Internees to Australia During the First World War, Journal of the Australian War Memorial, no 5, October 1984, pp 36–43

[5] Anthony Splivalo, The Home Fires, Fremantle Arts Centre Press, Fremantle, WA, 1982

[6] Anthony Splivalo, The Home Fires, Fremantle Arts Centre Press, Fremantle, WA, 1982, p 90

[7] Don Godden, Beverley Johnson, Matthew Kelly and Dominic Steele, 'Archival Recordings', First Field Hospital Site, Holsworthy, vol II, Godden Mackay, Sydney, 1995, pp 22

[8] Anthony Splivalo, The Home Fires, Fremantle Arts Centre Press, Fremantle, WA, 1982, pp 91–92

[9] Don Godden, Beverley Johnson, Matthew Kelly and Dominic Steele, 'Archival Recordings', First Field Hospital Site, Holsworthy, vol II, Godden Mackay, Sydney, 1995, pp 25–26

[10] Anthony Splivalo, The Home Fires, Fremantle Arts Centre Press, Fremantle, WA, 1982, p 95

[11] Don Godden, Beverley Johnson, Matthew Kelly and Dominic Steele, 'Archival Recordings', First Field Hospital Site, Holsworthy, vol II, Godden Mackay, Sydney, 1995, p 25

[12] Don Godden, Beverley Johnson, Matthew Kelly and Dominic Steele, 'Archival Recordings', First Field Hospital Site, Holsworthy, vol II, Godden Mackay, Sydney, 1995, p 23

[13] Anthony Splivalo, The Home Fires, Fremantle Arts Centre Press, Fremantle, WA, 1982, p 94

[14] Don Godden, Beverley Johnson, Matthew Kelly and Dominic Steele, 'Archival Recordings', First Field Hospital Site, Holsworthy, vol II, Godden Mackay, Sydney, 1995, p 22

[15] Anthony Splivalo, The Home Fires, Fremantle Arts Centre Press, Fremantle, WA, 1982, p 96

[16] Anthony Splivalo, The Home Fires, Fremantle Arts Centre Press, Fremantle, WA, 1982, pp 96–97

[17] Don Godden, Beverley Johnson, Matthew Kelly and Dominic Steele, 'Archival Recordings', First Field Hospital Site, Holsworthy, vol II, Godden Mackay, Sydney, 1995, pp 32–33

[18] Don Godden, Beverley Johnson, Matthew Kelly and Dominic Steele, 'Archival Recordings', First Field Hospital Site, Holsworthy, vol II, Godden Mackay, Sydney, 1995, p 31

[19] Don Godden, Beverley Johnson, Matthew Kelly and Dominic Steele, 'Archival Recordings', First Field Hospital Site, Holsworthy, vol II, Godden Mackay, Sydney, 1995, p 27

[20] Don Godden, Beverley Johnson, Matthew Kelly and Dominic Steele, 'Archival Recordings', First Field Hospital Site, Holsworthy, vol II, Godden Mackay, Sydney, 1995, pp 33–34

[21] Don Godden, Beverley Johnson, Matthew Kelly and Dominic Steele, 'Archival Recordings', First Field Hospital Site, Holsworthy, vol II, Godden Mackay, Sydney, 1995, p 30

[22] Don Godden, Beverley Johnson, Matthew Kelly and Dominic Steele, 'Archival Recordings', First Field Hospital Site, Holsworthy, vol II, Godden Mackay, Sydney, 1995, p 36

[23] Henry Stead, Stead's Review of Reviews, vol 52, no 5, 4 March 1920, pp 268–270

[24] Don Godden, Beverley Johnson, Matthew Kelly and Dominic Steele, 'Archival Recordings', First Field Hospital Site, Holsworthy, vol II, Godden Mackay, Sydney, 1995, p 37

[25] Frank Doak, 'The Good Life (or Concentration Camp Capers)' in Australian Defence Heritage, The Fairfax Library, Broadway, NSW, 1998, pp 89–94

.