The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

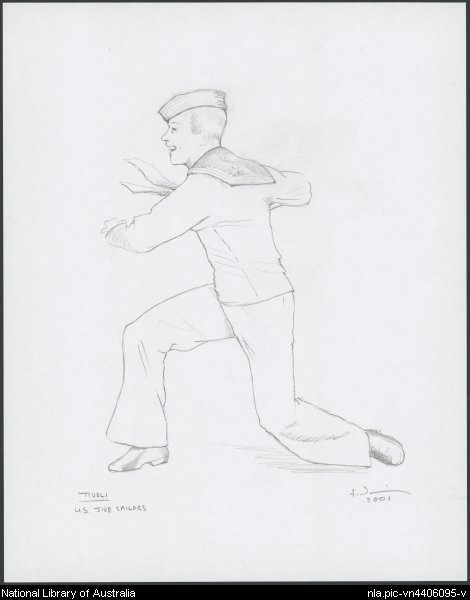

Graeme Murphy's Tivoli

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Graeme Murphy's Tivoli

You [media]could see they were Tivoli girls from the glimpses of their legs from the knees down; 'great pins', as they said in the '40s. Graeme Murphy admired them. Everyone admired them, especially the dancers of the Sydney Dance Company and the Australian Ballet who cheered as the lineup of former Tivoli showgirls walked into the Sydney Dance Company studios one Tuesday in December 2000.

[media]Even their names brought back the era when vaudeville was king, when the nudes on stage never moved and when the ballet lovelies high kicked and time-stepped in two shows a day, every day of the week. That Tuesday, Joycie and June and Ruby sat in line with Linda Nagle and sang the wartime anthem of the Tivoli Circuit:

A brown slouch hat, with the side turned up

And it means the world to me

It's the symbol of our nation

The land of liberty. [1]

The Sydney Dance Company's home at Pier 4, Walsh Bay, holds many memories, but that moment – when Murphy brought the veteran dancers face-to-face with the young women who would portray them in his Tivoli show – was one of the most poignant. When Tivoli, a coproduction of Sydney Dance Company and the Australian Ballet premiered the following year, Murphy's tribute to the vaudeville circuit was a reflection of his love of the nation's theatrical past and his constant commitment to portray Australia and Australians on stage. As Murphy recalled:

When I was nine or 10, I saw a show called Oriental Cavalcade [a Tivoli show touring to Tasmania]. My parents took me to Launceston from the bush to see it. I was blown away because it was the most theatrical thing I've seen apart from my parents' school concerts. I suspect that was the real germ of a career in dance. [2]

Arrivals and departures

Within seven years of the Tivoli production, Murphy's three decades at the helm of Sydney Dance Company were over. He and his wife, Janet Vernon, packed up their belongings and left the upstairs offices at Pier 4, frustrated with the never ending pressure of inadequate funding. Their young successor, Tanja Liedtke, was killed in a road accident in 2007 before she even took up the artistic directorship, a tragedy that will never be forgotten in the Sydney dance world. [3]

The brave dancers then worked for three different guest choreographers – Meryl Tankard, Rafael Bonachela and Azure Barton – before Bonachela was appointed artistic director in 2008. In those limbo years, tears were shed as dancers came and went but the Sydney Dance Company did not fall apart. After all, there will always be more eager dancers than there are professional jobs and once dancing is in the soul, it's hard to expunge.

Daily proof can be seen at the Pier 4 studios where classes for amateurs and professionals are held every day in four big studios. The history of the site and the company is written in the studio walls, the ironbark pillars, the solid floors, the windows overlooking the shimmering harbour and in all the spaces in and around the studios where choreographers, teachers and dancers – so many dancers – have sweated and puffed, danced a routine one more time, and another and another, until sweat trickled down their brows and backs and the tinkle of the piano kept them moving on. They prepare for class, with their hands on the barre, a place where there is only the moment, and where the only sounds that matter are the music and the teacher's voice.

A site of contrasts

The place where the dancers now stand was once the site for a different kind of physical effort. Pier 4 (and the adjacent Pier 5, home to the Sydney Theatre Company) were working wharves, servicing cargo vessels from 1922. The daily shipping news in The Sydney Morning Herald documented the arrivals and departures well into the mid-twentieth century. But with the arrival of containers, the finger wharves at Walsh Bay fell quiet.

In the 1980s, Elizabeth Butcher, general manager of the National Institute of Dramatic Arts, suggested that the cavernous empty buildings might become a new creative hub. The NSW government agreed and commissioned the architect, Vivian Fraser, in association with the government architect, JW Thomson, to recreate Piers 4 and 5 into homes for the Sydney Dance Company and Sydney Theatre Company. Their approach earned them accolades and awards with one jury praising the architects' new work as "clearly distinguishable as a layer – albeit a transparent one – which allows us to see through to something older underneath". [4] The site has always been one of contrasts.

In the early twentieth century, the timber wharves were built from sturdy Australian hardwood turpentine trees yet the working wharves appeared both delicate and elegant as they extended far from the shoreline, resting on row upon row of timber piles. Barry McGregor, an architect who worked with Fraser on the design recalls how "we developed an approach to build a building inside a building…you don't try to match [the old with new], you contrast". [5] In Sydney Dance Company's mezzanine level timber beams contrast with black painted steel beams which in turn contrast with the original federation structure. The administrative headquarters of the Sydney Dance Company and Sydney Theatre Company "might be a little hot or a little cramped", said McGregor, "but they are a marvellous place to work". [6]

As the studios are for the dancers, whether in class or in rehearsal. Each dancer looks at his or her individual reflection in the big mirrors but collectively, they are part of a community, moving within a building whose history resembles a kaleidoscope of memories: Kristian Fredrikson, the designer, and Graeme Murphy, working on their production of Swan Lake, one of the last that Fredrikson designed before his death; Darcey Bussell, standing at the barre, getting back into performance form for her appearance at the closing ceremony of the 2012 London Olympics; and young boys and girls auditioning for the children's roles in Murphy's Nutcracker. Hours and hours went by as the numbers were whittled away with anxious parents waiting in the café area outside.

On her first day in the Sydney Dance Company studios, guest choreographer, Azure Barton, asked the weary dancers a question: "For every year you've been in the company", she said, "can you remember a significant moment? Now, break it down into one moment representing each year". [7] For Bradley Chatfield, then 37, it was an exercise in remembering. He joined the company in 1991. That meant recalling 17 different moments. From all the gestures and moves he made, Barton chose one to incorporate in her work – the way he held his hand over his open mouth. That might have represented all the dramas and tragedies of the company's life for the past two decades or simply a snippet from one of Chatfield's many roles, from the Beast, in Beauty And The Beast, King Herod in Salome, or Eros in Mythologia, in which he wore feathered wings, a codpiece and pointe shoes.

As Vivian Fraser once said of Piers 4 and 5: "It's the most magic site". [8]

Notes

[1] A Brown Slouch Hat, written by George Wallace, published J Albert and Son, Sydney, 1942

[2] Valerie Lawson 'How the Tivoli Sealed its Place in Hysteria', Sydney Morning Herald, 15 December, 2000

[3] 'Passion and Promise Snuffed Out', obituary, Sydney Morning Herald, 21 August 2007

[4] Citation by jury of Institute of Architects, 1985

[5] Valerie Lawson, interview with Barry McGregor, October 2013

[6] Valerie Lawson, interview with Barry McGregor, October 2013

[7] Valerie Lawson, 'The Cult of Personality', Sydney Morning Herald, 9 September, 2008

[8] Meg Stewart, 'Creative Spirit: Vivian Fraser', Sydney Morning Herald, 23 April, 1996

.