The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Governesses

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Governesses

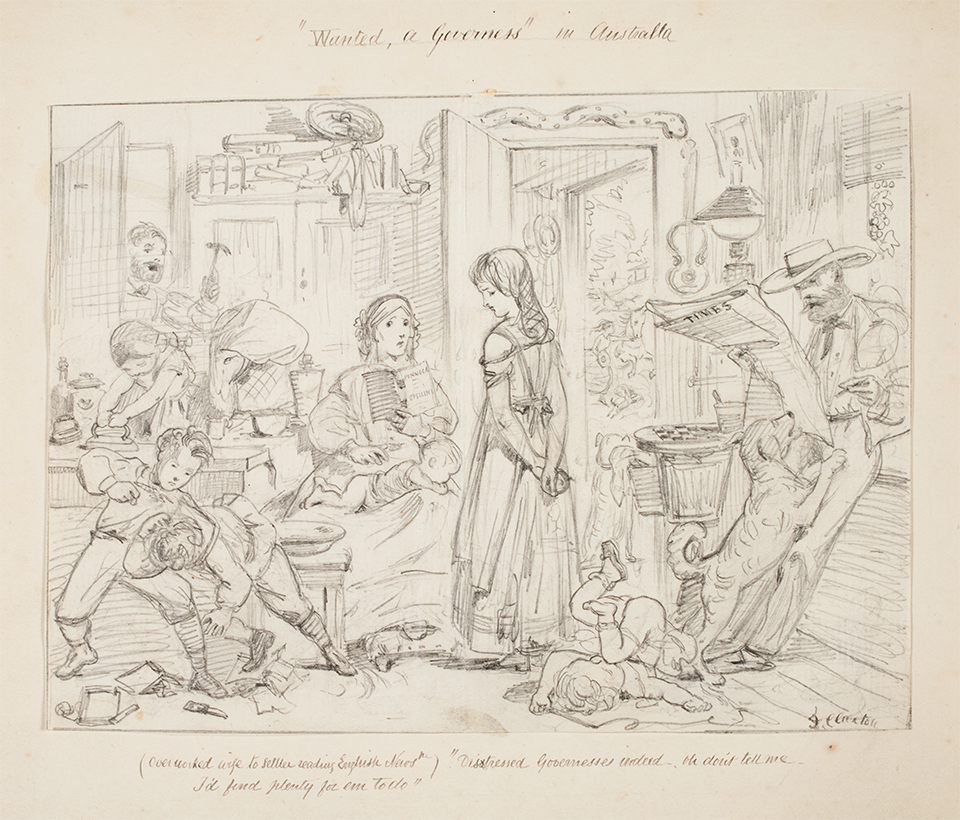

Governesses [media]held an important place in Sydney's economic and social life during the nineteenth and very early twentieth centuries. As the main providers of female education and accomplishments, governesses occupied an interesting social position. They usually lived with the families they worked for, but were not part of them. They were present at many social engagements, but usually as a chaperone. The governess's ability to teach her pupils, both traditional subjects such as English and French, and drawing room accomplishments such as dancing and singing, was only ever as good as her own education had been, which in turn impacted on her ability to earn a good salary. A vocation for teaching was rarely as strong a consideration as the need to earn a living, and working as a governess was one of the few respectable nineteenth-century occupations for women.

The first governess in Sydney

The first governess in the Australian colonies was employed by John Macarthur. Miss Penelope Lucas emigrated to Sydney on the Argo in 1805 as governess to the Macarthurs' eldest daughter. At 37 years old, Miss Lucas was probably seen as quite matronly with no danger of developing romantic designs on the Macarthur sons. [1] Miss Lucas taught all of the younger Macarthur children, and especially the usual range of accomplishments for the girls. There is no record of exactly what the Macarthur daughters learned in Miss Lucas's schoolroom, but it was most likely music, drawing and languages as well as a basic grounding in English literature and history. In an unusual development, the Macarthurs developed such a strong bond with Miss Lucas that they built her a cottage on the Elizabeth Farm estate at Parramatta. Hambledon Cottage, as she named it, still exists, although it is no longer considered part of the property. [2] Miss Lucas died in 1836 at the age of 68, and St John's Anglican Cathedral at Parramatta holds a record of her memorial service and her other activities within the community. [3]

The term 'status incongruence' was coined by M Jeanne Petersen and, although a little clumsy, remains the best description to convey the social position of the governess. [4] The English governess was 'a lady in every sense of the word'. She had to come from a good family, be well educated, be able to teach the accomplishments and navigate a drawing room in a socially acceptable manner and, overall, be everything a lady should be. [5] As noted by an astute commentator later in the century:

We suppose that nobody becomes a governess from choice. That is, a young woman would rather marry if the right man would marry her, or stay in her father's house if he could afford to keep her there. [6]

However some ladies did not have the opportunity to marry, and could not rely on their families for financial support. They were therefore forced to earn their own livings in some way. Therein lay the problem. A lady did not work. Therefore a lady who became a governess was something less than a lady, and as a consequence lost some of her status in respectable society. The ambivalent social position of the governess was imported from England to the young town of Sydney. Penelope Lucas, therefore, was quite likely only a fitting companion for Mrs Macarthur when no other company was available. While she may well have attended a number of the social functions in Sydney over the 30 years that she lived in the growing city, many of those would have been in her capacity as chaperone for the unmarried Macarthur ladies.

A trickle becomes a steady stream

In the decades following Penelope Lucas's arrival in Sydney, a steady trickle of governesses were induced to emigrate from England by wealthy Sydney families. There was, however, a problem in that governesses were by definition single women (either never married or widowed) and, in a rapidly growing and prosperous colony, they did not remain single for long. Mrs Phillip King engaged Charlotte Waring in England to emigrate as governess to the children of Hannibal and Maria Macarthur. [7] However, Charlotte arrived in Sydney already engaged to James Atkinson, whom she had met on board ship. [8] Perhaps not wanting to offend so powerful a family, Charlotte does appear to have worked for the Macarthurs as governess for a short time before she married. However, it is clear that governessing for many women was simply a stop-gap between leaving the protection of their family homes and making suitable marriages.

The [media]families who employed governesses in Sydney were generally wealthy, well-established people who valued their social position. Despite this, governesses were sometimes seen as luxuries, and were employed after other servants had been well entrenched in the household. [9] Competition for good servants was fierce, but in Sydney the supply of governesses consistently exceeded the demand for them. A typical family would employ their servants, and then see how much money was left over to pay the governess. Even in very wealthy families, cash flow could be intermittent, depending on their sources of funds.

Governesses who could teach English, French, drawing and music commanded good jobs and reasonable salaries. They were never regulated or tested for their proficiency, and the term 'an indifferent education' could readily be applied to the kind of rudimentary teaching that many governesses were capable of giving to their students. Although some governesses had certificates for English, languages and music, these were not always considered valuable by potential employers. Debates played out in the Sydney Morning Herald during the 1850s asked whether girls needed to be taught everything, and therefore whether governesses needed to be able to teach everything. [10] Some thought this would lead to a very basic understanding of many things, instead of girls developing more comprehensive skills in the subjects they actually enjoyed. However, job advertisements continued to list an extensive range of subjects that governesses were expected to be able to teach. Broad but shallow knowledge was considered more appropriate for female education than deeper mastery of fewer areas.

The term governess has occasionally been used to describe some teachers in nineteenth-century private schools. [11] Some governesses did find work in private schools, which were usually of a lower standard than government schools. There were some measures undertaken to remove substandard teachers from government schools from the 1850s onwards, but private schools remained unregulated for a few more years and proved to be a haven for those governesses who could not find a traditional governessing role. [12]

Over the [media]course of the century, governesses continued to emigrate to the Australian colonies, with Sydney second only to Melbourne in popularity. Governesses often travelled out with families to teach and mind the children on the voyage. While some stayed with families after arrival, many were dismissed when the family reached port, and so joined the ranks of governesses already looking for work.

The Female Middle Class Emigration Society governesses

In 1861, the first five governesses arrived in Sydney under the auspices of the Female Middle Class Emigration Society (FMCES). [13] Miss Maria Rye, who formally established the Society a year later, was convinced that surplus women in England could find better jobs, better pay and, perhaps, more potential marriage partners in the colonies than in England. [14] These five women – Emily Streeter, Gertrude Gooch, Ellen Ireland, Rosa Phayne and Georgiana Moundsen – were the first to see if the Society could deliver on its vision.

Unfortunately it did not. Georgiana Moundsen was the most fortunate one of the five, as she met Edward Andrews on the Rachel . They were engaged before the boat docked in Sydney in September 1861, and married on 23 January 1862. The other four women struggled to find work in Sydney, and ranged from Goulburn to Newcastle over the next few years as work opportunities arose. Like many of the English immigrant governesses, Ellen Ireland suffered from the heat and had extended periods of ill-health. This made it much more difficult for her to repay the loan of her passage money from the Society, and she wrote in 1862 that

I only wish it was in my power to send you some money … but I have been truly unfortunate in being so ill ever since my arrival here. [15]

Emily Streeter had more success, and found two positions that seem to have suited her. Using Sydney as a base to return to each time, she worked first at Jerrys Plains, and then at Penrith. [16]

Between 1861 and 1888, 30 FMCES emigrants arrived in Sydney. We do not know all of their names, as the FMCES went to some lengths to protect the privacy of the women they assisted. Of those who disembarked in Sydney, 83 per cent found work as governesses from a Sydney base, although many of them had to travel to country stations for their employment. Continuity of employment remained a big concern for these women, and some, such as Annie Davis, had as many as seven jobs in less than four years. Being able to teach music was considered indispensable. Louisa Dearmer, a newly arrived immigrant governess in 1868, wrote that Sydney residents had 'a mania for music'. [17] It was commonly agreed among these governesses that for those unable to teach music, work was very difficult to find; but even with musical skills, finding and retaining regular work was still challenging.

The usual method of finding work for Sydney governesses during this period was either 'through friends, or an agent', although finding a situation through friends was less socially risky than using an employment agent. [18] One such agent working in Sydney was Mrs Augustus Dillon, wife of the postmaster at the General Post Office, who charged half a guinea as a registration fee and 5 per cent of the first year's salary for her services in 1863. [19] By all accounts she was quite an effective agent; however some governesses felt that their own social standing was threatened by their dealings with her. [20]

Protecting social standing became important in other aspects of a governess's life. From the 1850s onwards, there was another wealthy group in Sydney who valued their governesses more highly. These were the nouveaux riches, those who had made their money within the current generation through gold, commercial or pastoral interests and had therefore never learned the airs and graces required to navigate a drawing room successfully. These families employed governesses to give their daughters the polish required to attain the social position to which they aspired, and to which money alone could not give them entry. However, perhaps understandably, they did not want their social shortcomings to be highlighted. Governesses, particularly English ones, complained that they could only teach by example and were not allowed to correct their pupils. Gertrude Gooch wrote in February 1862 that

Mothers prefer you to fall into their ways in preference to introducing your own and they do not like to be made to feel inferior. [21]

Sydney had a Home for Governesses and Female Servants, which provided accommodation to those governesses looking for situations. It also served 'as a registry office, where ladies may obtain governesses … and governesses … may obtain situations'. [22] The charge for accommodation was 11 shillings and sixpence per week, and governesses were exempt from domestic duties while staying in the home. They also took their meals with the Matron, a sign that they were considered her social equivalent. [23] By contrast, the domestic servants paid 10 shillings and sixpence per week, were expected to help with the housework of the Home, and took their meals separately. The Sydney Home did not enjoy a good reputation among the newly arrived English governesses. They would use the registry service, but many refused to stay there despite the fact that staying at the Home was cheaper than finding independent lodgings of their own. [24]

Many of the letters written by the FMCES emigrants to the Society mention the salaries that they received. From these figures it is possible to determine that the average FMCES emigrant governess in Sydney was earning approximately £62 per annum between the early 1860s and the late 1880s. As most of these governesses were living with the families who employed them, the real remuneration is probably closer to £100 per annum when food, board and laundry are taken into account.

However, another source of information tells a different story. At various times during the latter half of the nineteenth century, governesses and interested members of the public conducted emotional debates in the letter pages of the Sydney Morning Herald. Many of these correspondents claimed that a governess was barely paid the same as a cook, sometimes less, and that her duties were demeaning. The debate started in April 1854, with 'Q' writing to the editor of the Herald that

A lady advertises for a governess to educate two young ladies, for £30 a year! and to this important duty it is hinted that some assistance in the domestic management will be required of her. I wonder what the lady gives her cook or housemaid. [25]

An 'Old Governess' wrote to the Herald in 1863, in response to an advertisement for a governess paying £40, when a cook could ask £40–50, that 'if talent is required ought it not to be appropriately paid for'. [26] In March 1889, a vigorous debate played out in the pages of the Herald, with one side arguing that governesses were difficult to employ because they refused to assist with household tasks, while the other argued that governesses were well educated gentlewomen who were employed to teach, not to be taken advantage of like common servants. [27]

Some governesses were obviously finding it increasingly difficult to retain their status as 'almost a lady'. Most of the writers do not go into much detail, probably because their contemporary readers would already be well versed in these issues, but their complaints about governesses being expected to perform household chores in addition to teaching were echoed elsewhere. 'Justitia', writing to the Herald in 1862, strongly urged governesses to use lawyers to draw up their employment agreements, to save themselves the difficulty of finding that a situation was not exactly what had been advertised. [28] Sound advice, but difficult to follow for those governesses who wanted to start their employment on a more socially acceptable footing.

Two different strata of governesses may be represented here. The first was made up of reasonably well accomplished governesses who were capable of beating some healthy competition to secure well paid and comfortable situations. The other group were significantly less qualified women desperate to earn their livings but resentful of the loss in status that their working conditions inflicted on them. 'An Anxious Inquirer' referred to herself as 'one of that oppressed class styled Governesses'. [29] Another, using the pseudonym of 'Humanity', lamented that

advertising columns contain, almost daily, advertisements requiring the services of educated gentlewomen as governesses at salaries far below those given to many at domestic services.

A few months later she wrote of another example where £30 per annum was offered for a position with three pupils, and for which some domestic duties would be required. [30] As the number of governesses looking for work in Sydney increased, the usual effect of excess supply over demand reduced their salaries, their working conditions and their social status.

The salary for a teacher in a government school could be much higher than that earned by a governess. Louisa Dearmer reported her starting salary to be £150 in 1868. [31] However to be eligible for such positions, governesses had to pass an examination. Even many of those governesses who were considered to be reasonably accomplished could not pass the examinations, but that was soon to change.

The rise of the colonial-born governess

By the 1860s there were quite a few colonial-born women working as governesses, but they were not as numerous as those born in England or elsewhere in Europe. They are mentioned in letters from the FMCES emigrants back to England, and a number of famous Australian women, such as Mary MacKillop and Miles Franklin, were governesses for a short time before moving on to bigger and better things. [32] However there is no evidence that anyone particularly famous worked in the greater Sydney region.

The number of colonial-born governesses achieving significant degrees of success rose from the 1880s onwards. As a result of improvements in schools, they were much better educated than their English counterparts, and many were able to pass the University of Sydney examinations in a variety of subjects. Jane Taunton was one of the first women to pass the University's Junior Public Examination in 1887. [33] Alice Armstrong passed the same exam in 1892 in history, geography, mathematics and geology. [34] These advanced qualifications raised the levels of education that could be demanded from governesses, and reflected the shift in educational focus for girls from the traditional accomplishments of music, drawing, dancing, and languages towards an educational regime similar to that which had long been available to boys. The list of subjects that employers were seeking governesses to teach had grown considerably, and now included English, Latin, French, German, geometry, algebra, trigonometry, physical science, drawing, painting in oils, piano, singing, dancing and needlework. [35]

Highly accomplished European governesses could still make their mark in the later nineteenth century. One of the most successful governesses to make the transition to teaching was the German-born Marie Wallis, who went on to found Ascham School in 1886. [36]

The decline of the governess in Sydney

The number of governesses working in the immediate Sydney area started to decline slowly from the 1880s, and significantly from the turn of the century. Better quality schools, including Ascham in Darling Point (now at Edgecliff) and Arnold's College for Girls (later Redlands) in North Sydney meant that wealthy families could provide good educations for their daughters without the inconvenience of teaching them at home. While the Sydney Morning Herald still published advertisements for the services of governesses into the 1950s, they were usually seeking governesses to travel to rural properties, which suggests that there were very few women still working in this capacity in the greater Sydney area.

References

Patricia Clarke, The Governesses: Letters from the Colonies 1862–1882, London, 1985

Marion Diamond, Emigration and Empire: The Life of Maria S Rye, Garland, New York, 1999

Gwenda Jones, 'A Lady in Every Sense of the Word: A Study of the Governess in Australian Colonial Society', MA thesis, University of Melbourne, 1982

Patricia Kiger, 'Class, Social Position, and the Occupation of Governess in Mid-Nineteenth Century England', MA thesis, California State University Dominguez Hills, Summer 2001

M Jeanne Peterson, 'The Victorian Governess: Status Incongruence in Family and Society', in Martha Vicinus (ed), Suffer and Be Still: Women in the Victorian Age, Methuen, London, 1980

Miranda Walker, 'No one loses caste if they work: The Writing of Catherine Helen Spence and Changing Notions of Femininity in British Middle-Class Women Migrants to the Australian and New Zealand Colonies, 1840–90', Exploring the British World: Identity, Cultural Production, Institutions, Melbourne, 2004, pp 765–786

Records – Female Middle Class Emigration Society, National Library of Australia, AJCP, Part 8, Reel M468

Notes

[1] 'Hambledon Cottage', Sydney Architecture website, http://www.sydneyarchitecture.com/WES/WES02.htm, viewed 24 June 2011

[2] Hambledon Cottage is no longer obviously connected to the Elizabeth Farm property. They are separated by a road and managed separately – Hambledon Cottage by the Parramatta and District Historical Society, Elizabeth Farm by the Historic Houses Trust

[3] 'Hambledon Cottage', Sydney Architecture website, http://www.sydneyarchitecture.com/WES/WES02.htm, viewed 24 June 2011

[4] M Jeanne Peterson, 'The Victorian Governess: Status Incongruence in Family and Society', in Martha Vicinus (ed), Suffer and Be Still: Women in the Victorian Age, Methuen, London, 1980

[5] There are a number of excellent sources that discuss this in enormous detail. They include: Patricia Kiger, 'Class, Social Position, and the Occupation of Governess in Mid-Nineteenth Century England', MA thesis, California State University Dominguez Hills, Summer 2001, pp 2–3, 9–10, 15; Miranda Walker, 'No one loses caste if they work: The Writing of Catherine Helen Spence and Changing Notions of Femininity in British Middle-Class Women Migrants to the Australian and New Zealand Colonies, 1840–90', Exploring the British World: Identity, Cultural Production, Institutions, Melbourne, 2004, pp 767–768; PJ Miller, 'Women's Education, 'Self-Improvement' and Social Mobility – A Late Eighteenth Century Debate', British Journal of Educational Studies, vol 20, no 3, October 1972, pp 306–307, 312; M Jeanne Peterson, 'The Victorian Governess: Status Incongruence in Family and Society', in Martha Vicinus (ed), Suffer and Be Still: Women in the Victorian Age, Methuen, London, 1980; Gwenda Jones, 'A Lady in Every Sense of the Word: A Study of the Governess in Australian Colonial Society', MA thesis, University of Melbourne, 1982, pp iii, 46, 262; Elizabeth Dana Rescher, 'The Lady or the Tiger: Evolving Victorian Perceptions of Education and The Private Resident Governess', PhD thesis, University of Toronto, 1999, pp 1–2; Marion Diamond, Emigration and Empire: The Life of Maria S Rye, Garland, New York, 1999, p 95

[6] 'Wanted, A Governess', Sydney Morning Herald, 29 November 1859, p 8

[7] Gwenda Jones, 'A Lady in Every Sense of the Word: A Study of the Governess in Australian Colonial Society', MA thesis, University of Melbourne, 1982, pp 32–33

[8] Public Place Names (Franklin) Determination 2006 No 1, http://www.legislation.act.gov.au/di/2006-215/current/pdf/2006-215.pdf, p 7, viewed 24 June 2011

[9] Marion Diamond, Emigration and Empire: The Life of Maria S Rye, Garland, New York, 1999, p 147; 'Educated Women in Australia', Brisbane Courier, Wednesday 22 December 1886, p 3

[10] 'Wanted, A Governess', Sydney Morning Herald, 29 November 1859

[11] It is used to describe two of the teachers at St Augustine's Girls School in Balmain in 1899, although this seems to have been the only time in during the 1800s that this occurs in the Australian papers. 'St Augustine's Girls School, Balmain', Sydney Morning Herald, 21 December 1899, p 10

[12] Gwenda Jones, 'A Lady in Every Sense of the Word: A Study of the Governess in Australian Colonial Society', MA thesis, University of Melbourne, 1982, p 28

[13] FMCES Report, '1st report – 1861', p 7; JE Lewin, 'Female Middle Class Emigration', a paper read at the Social Science Congress in October 1863, p 1, Records – FMCES, National Library of Australia, AJCP, Part 8, Reel M468

[14] For a more detailed discussion on the FMCES and their vision, see the forthcoming article: Kate Matthew, 'The FMCES Governesses in Australia: a failed vision', Journal of Australian Colonial History, 2012. Also Marion Diamond, Emigration and Empire: The Life of Maria S Rye, Garland, New York, 1999, p xviii

[15] Ellen Ireland to Maria Rye, letter, 28 May 1862, FMCES letter book 1, p 18

[16] Emily Streeter to Maria Rye, letter, 20 May 1862, FMCES letter book 1, p 21

[17] Louisa Dearmer to Jane Lewin, letter, 1 June 1868, FMCES letter book 1, p 308

[18] Justitia, 'Governesses' Agreements', Sydney Morning Herald, 2 September 1862, p 5

[19] Annie Davis to Jane Lewin, letter, September 1863, FMCES letter book 1, p 86

[20] Annie Davis to Jane Lewin, letter, September 1863, FMCES letter book 1, p 86

[21] Gertrude Gooch to Maria Rye, letter, 17 February 1862, FMCES letter book 1, p 10

[22] 'The Charitable Institutions of Sydney', Sydney Morning Herald, 17 January 1867, p 3

[23] 'The Charitable Institutions of Sydney', Sydney Morning Herald, 17 January 1867, p 3

[24] Annie Davis to Jane Lewin, letter, September 1863, FMCES letter book 1, p 89; Mary Richardson to Miss Blyth, letter, 13 February 1863, FMCES letter book 1, p 49

[25] Q, 'Governesses', Sydney Morning Herald, 11 April 1854, p 5

[26] An Old Governess, 'Governesses' Salaries', Sydney Morning Herald, 28 July 1863, p 3

[27] See the letter pages of Sydney Morning Herald editions for March 1889

[28] Justitia, 'Governesses' Agreements', Sydney Morning Herald, 2 September 1862, p 5

[29] 'Wanted A Governess', Sydney Morning Herald, 22 May 1873, p 5

[30] Humanity, 'The Unfortunate Governess', Sydney Morning Herald, 20 April 1888, p 5; Humanity, 'The Unfortunate Governess Again', Sydney Morning Herald, 17 August 1888, p 4

[31] Louisa Dearmer to Jane Lewin, letter, 1 June 1868, FMCES letter book 1, p 308

[32] Annie Davis to Jane Lewin, letter, September 1863, FMCES letter book 1, pp 89–90

[33] Gwenda Jones, 'A Lady in Every Sense of the Word: A Study of the Governess in Australian Colonial Society', MA thesis, University of Melbourne, 1982, p 200

[34] Record for Alice Armstrong, p263, Reel No FCN 98, Catalogue Number 1036/4, Records of Service, Education Department 1892–c1910, State Archives of Western Australia

[35] Edgar R Hoskins, 'Tutors and Governesses', Sydney Morning Herald, 26 February 1889, p 8; A Governess, 'Governesses', Sydney Morning Herald, 2 March 1889, p 7

[36] 'The search for Marie Wallis', Ascham School website, http://www.ascham.nsw.edu.au/news.asp?id=83, viewed 24 June 2011

.