The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Golf

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

In his book Sport and Pastime in Australia, published in 1912, [1] Gordon Inglis noted that although

some Scottish pioneers introduced the game [in Australia] in the [eighteen] forties, it was not until the early nineties that the great revival of golf on the other side of the world led to a club being established in Melbourne. [2]

The Melbourne Golf Club had been formed in 1891, and the Sydney (later Royal Sydney) Golf Club was inaugurated two years later. Following British developments, the prestige attached to a proper golf club led Inglis to contend that in

the early days of Australia the first task undertaken by any new settlement was the planning of a race-course. To-day a golf-course would be laid out. [3]

Community organisations such as sports clubs became vehicles of social agency, class formation and community stabilisation. [4]

Playing golf in the suburbs

The [media]desire for golf courses and clubs in the formation of middle-class and bourgeois suburbs was evident in Sydney. A mushrooming of Sydney's metropolitan golf courses coincided with the boom in suburbanisation after World War I and through the 1920s. The number of golf courses tripled in this period, from 9 in 1900 to 29 in 1929. Virtually all of these courses were in middle-class and bourgeois suburbs that were predominantly Protestant, and around half of them were located on the north shore. A similar, though quantitatively far more spectacular, phenomena occurred in the United States of America. There, the number of golf clubs rose from 472 in 1917 to 5856 by 1930. Ninety per cent of these were private establishments, [5] as were the vast majority on the Cumberland Plain.

Class and race in golf

Golf in Sydney, as in the rest of Australia, did not generally have the egalitarian association that it had in Scotland. [6] Rather, Sydneysiders viewed the game in its British context. Golf was perceived to be elitist; it was 'gentle' and connoted good birth, honour and respectability. Promoters of 'one of Scotland's greatest gifts to the human race', as Lloyd George once famously remarked, were tireless in extolling the 'progress of the game' brought about by the evolution of 'democratic tendencies'. Grantham Money, editor of the Australian Golfer, wrote in a special feature in The Lone Hand,

Not many years ago the word golfer was to many people synonymous with the term 'snob', and it was the idea that it was a game in which class distinction was more than usually prevalent that had a great deal to do with its lack of popularity as a national pastime. In those days the number of courses was comparatively small, and the necessity for placing a limit on membership was even greater than it is to-day. As a result the clubs were more exclusive, and many people who might have become devotees never had the opportunity of falling victims to the fascination of the game. [7]

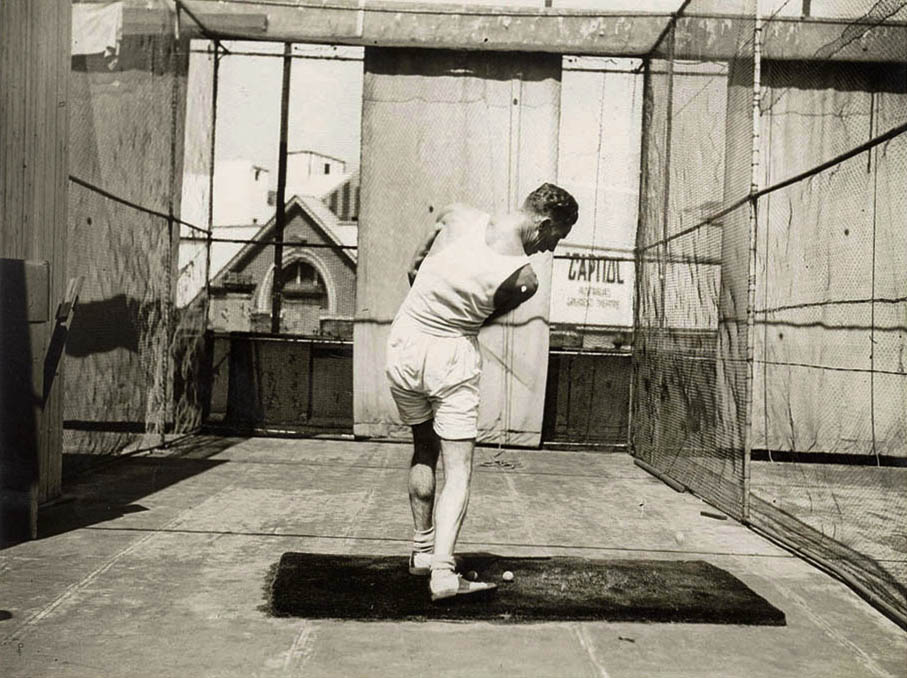

Some golf courses, notably Moore Park just south of the city, were open to the public. Golfing and other magazines occasionally featured articles on working-class men such [media]as Joseph Kirkwood, the lad from Manly who worked his way up from caddie to club professional, and Harry Sinclair, Redfern-born Moore Park Golf Club member who turned professional after winning the Australian amateur title in 1924. [8]

Sporting prowess, however, did not automatically translate into social acceptance. People such as caddies were servants, a status that was evident in their general exclusion from club bars. [9] As in the United States, racial and ethnic as well as class exclusion was also overt. Perhaps the most well-known case of racial discrimination was the Royal Sydney Golf Club's entrenched anti-Semitism, which lasted into the 1980s. [10] Waiting lists and procedures for applying for membership were also employed to screen out undesirables or to cool the heels of upstarts. [media]Clubs such as that at Manly, with its mansion-like 'Golf House' and beautiful links, were renowned for their 'formidable waiting list[s]'. [11]

Reinforcing old social hierarchies and adopting appropriate codes – integrity, honour, civilised manners – golf was an antidote to modern influences and cultural practices. It also had the often intended effect of crystallising and quarantining classes. At Mosman, 'Swaggerdom' – as the Labor Daily dubbed members of the Mosman Golf Club – managed to secure 59 acres (24 hectares) of the Middle Head military reserve in 1924 on a 21-year, peppercorn lease on which they built a nine-hole course for almost £5,000 and a stone club house at an additional cost of £6,000. The entrance fee was 10 guineas (£10 10s) for full members. 'Ladies' paid a two-guinea fee. [12] In the mid-1920s the basic wage was around £4 per week.

By controlling membership intakes, setting entrance and membership fees, and regulating codes of behaviour and dress on the golf course and in the club house, these suburban clubs defined and redefined social hierarchies, and their members' places within them, as well as social values based on an acceptance of genteel ideals. [media]Thus one's social circle was protected from both unknown outsiders and those known or deemed to be socially inferior on the basis of their upbringing (as opposed to their status at birth) and respectability.

Golf and health

Along with other properly regulated sports, golf was, as Sir George Reid, New South Wales premier, later prime minister, and Australia's high commissioner in Britain, put it in his preface Inglis's Sport and Pastime in Australia, a healthy feature of a balanced and ordered national life. In the best of British traditions, the 'true sportsman', he observed, 'learns to obey, to exercise self-control, to subordinate self-interest'. [13]

Golf was also advanced as a remedy for modern pressures, nervousness and suburban fatigue. Scotland's greatest gift, [media]it was said, had done much for humanity from 'the health point of view'. There was, one writer was to argue,

no other form of sport which is so consistently recommended by the medical faculty for both men and women. It has in these days become almost more than a game. To many it is a necessity. It brings new life alike to the tired brain-worker and the weary housewife. It has probably saved more lives than all the drugs in the British pharmacopoeia. [14]

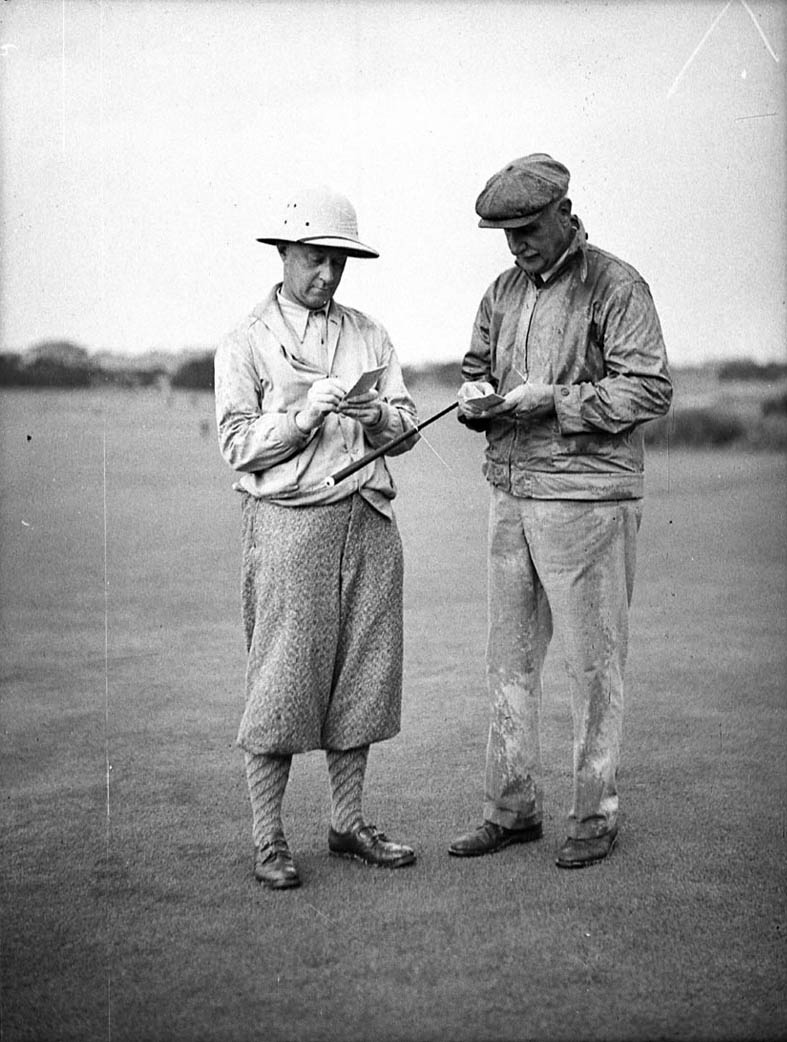

[media]Models to emulate or aspire to proliferated in the popular elite magazines. The Home featured regular spreads in the 1920s of 'society' playing 'gaily on' at prestigious courses such as the Royal Sydney. [15] Socialites, professionals and prime ministers appeared on golf links in the pages of The Home. [16]

As in other parts of Australia, the number of golfers in Sydney grew substantially from the 1950s until the 1980s. This was in part due to the long boom of the 1960s, suburban expansion and increased leisure time. [media]At the turn of the twenty-first century there are 58 public golf courses in Sydney and 75 private golf clubs. Around 400,000 people play golf across the metropolitan area at least once a year. Economically, the sport is important in terms of employment, leisure, tourism and manufacturing.

References

David J Innes, The story of golf in New South Wales, NSW Golf Association, Sydney, 1988

Brian Stoddard, 'Golf', in Wray Vamplew and Brian Stoddard (eds), Sport in Australia: A Social History, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1994

Colin Tatz and Brian Stoddart, The Royal Sydney Golf Club: the first hundred years, Royal Sydney Golf Club, Sydney, 1993

Notes

[1] Gordon Inglis, Sport and Pastime in Australia, Methuen, London, 1912, p 229

[2] Gordon Inglis, Sport and Pastime in Australia, Methuen, London, 1912, p 229

[3] Gordon Inglis, Sport and Pastime in Australia, Methuen, London, 1912, p 229

[4] Richard S Gruneau, Class, Sport and Social Development, University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst, 1983

[5] Kenneth T Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanisation of the United States, Oxford University Press, New York, 1987, p 99

[6] Brian Stoddard, 'Golf', in Wray Vamplew and Brian Stoddard (eds), Sport in Australia: A Social History, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1994, p 79; John Arnold, Riversdale Golf Club: A History 1892–1977, Riversdale Golf Club, Melbourne, 1977, chapter 1, 'Early Days of Golf in Australia', pp 13–18

[7] Grantham Money, 'How Golf Came to Australia', The Lone Hand, 1 February 1916, p 179

[8] DG Soutar, 'Kirkwood The Crack Australian Golfer', The Home, June 1920, pp 29–30; Brian Stoddard, 'Golf', in Wray Vamplew and Brian Stoddard (eds), Sport in Australia: A Social History, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1994, pp 82–3

[9] Brian Stoddard, 'Golf', in Wray Vamplew and Brian Stoddard (eds), Sport in Australia: A Social History, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1994, p 85

[10] Colin Tatz and Brian Stoddart, The Royal Sydney Golf Club: the first hundred years, Royal Sydney Golf Club, Sydney, 1993, pp 45–6

[11] Official Jubilee Souvenir to Commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the Incorporation of the Municipality of Manly 1877–1927, Manly Daily, Manly, 1927

[12] Gavin Souter, Mosman: A History, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1994, pp 210–11

[13] Gordon Inglis, Sport and Pastime in Australia, Methuen, London, 1912, p vii

[14] The Lone Hand, 1 February 1916, p 181

[15] The Home, 1 April 1926, p 3

[16] The Home, February 1926, p 72

.