The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Gay men

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Gay men

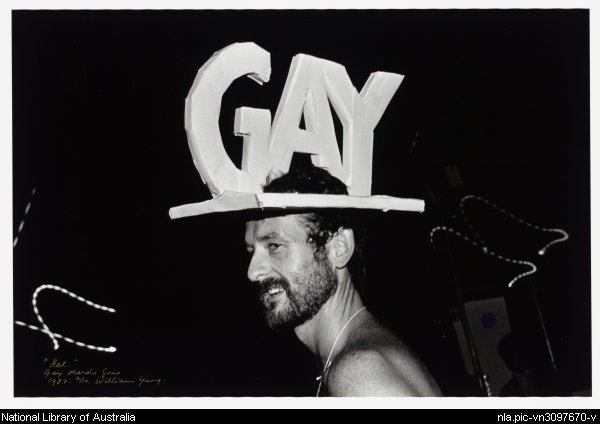

Early in February 2005, the Governor of New South Wales, Professor Marie Bashir, launching the annual Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras Festival, noted that this event had been 'absolutely priceless' in helping change social attitudes to sexual variation. This had helped create a more tolerant society:

Most Australians are increasingly taking pride in that sense of freedom which springs from the considerable diversity within our society – diversity of race, religion, culture and also sexual orientation.

Increasingly we have seen this diversity engender a greater environment of inclusiveness, respect and tolerance. Indeed, more than 'tolerance', – rather 'acceptance' – an acceptance and respect.[1]

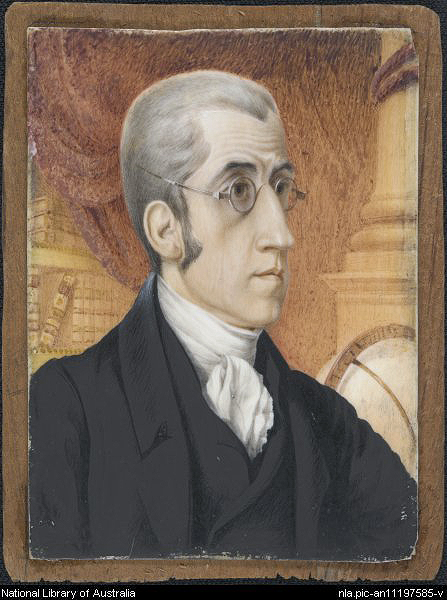

Such public approbation from the head of state is in stark contrast to the views, expressed over 200 years previously, by the first governor, Arthur Phillip:

There are two crimes that would merit death – murder and sodomy. For either of these crimes I would wish to confine the criminal till an opportunity offered of delivering him as a prisoner to the natives of New Zealand, and let them eat him. [2]

In the intervening centuries, attitudes to same-sex sexual activity, affection and relationships underwent dramatic changes, to the point where Sydney has acquired the reputation of being one of the iconic gay cities of the contemporary world. Yet the process has not been easy, and the major changes are only relatively recent. Indeed, over most of Australia's history since the white invasion of 1788, governments have actively persecuted those men who have been caught expressing their homoerotic desires, even though lesbian identity and behaviour were never criminalised in the same way.

Further adding to the complexities of social change, men with same-sex desires have seen themselves transformed from persons who might commit an act – sodomy – to persons with an identity inextricably bound up with their sexuality – homosexual or gay. Two centuries have seen attitudes and conceptualisations change dramatically.

A problem for writing a history of groups or communities designated criminal, demonised and persecuted over so much of our white history is both the relative paucity of records, and the bias in those that exist.

Three institutions of society – the law, the Christian churches, and the medical profession – have played particularly important roles in setting the parameters for controlling homosexuality, both directly and by conditioning the wider society's attitudes to homosexuality and thus how gay people can live. [media]This can be seen when we look back over the emergence of gay, lesbian, and what some now refer to as 'queer', life and subcultures in Sydney, from criminal secrecy within a disapproving society to such open activity, and at the more general changing attitudes to homosexuality in Australia.

The law

The [media]law is probably the most important constraint on people's lives. At its most basic level, it simply says what a society permits its members to do and what they must not do. Australian law, even until late in the twentieth century, still showed its derivation in many areas directly from English law. This reflected two things. Firstly, existing English law became the new colony's law with the Anglo-European invasion of 1788. As one expert on Australia's constitutional law has more poetically put it, as soon as

the original settlers had reached the colony, their invisible and inescapable cargo of English law fell from their shoulders and attached itself to the soil on which they stood. [3]

Secondly, English law and legal precedent continued to play an important role in Australian law until comparatively recent times. So laws relating to homosexuality have been overwhelmingly influenced by English developments until the very recent past.

Same-sex activity was never proscribed in the same way for women as it was for men, largely because what was criminalised was an act – sodomy – rather than an identity – gay or lesbian. Indeed, it wasn't until the late nineteenth century that the Hungarian Kartbeny 'invented' the term homosexual, which he saw as reflecting an identity, rather than just behaviour. Yet contrarily, and nearly a century later, Dr Alfred Kinsey suggested that on empirical evidence of human behaviour, there are no homosexuals, only homosexual acts. But the creation of an identity had dramatic consequences, for where an act could be committed by anyone, only those who were 'homosexualists' as they were called then, had their sexuality as a defining part of their identity. This debate continues today: does identity encompass everything? Are gays the same as everyone else, except for their sexual desires? Or is there something intrinsically different in being gay?

The churches

The legal constraints within which male homosexuals lived out their lives were originally taken from ecclesiastical law, reflecting the various Christian churches' attitudes to homosexuality. And for the Christian churches, sex and sexuality have always been a problematic area.

Until quite recently, and even still for some of the Christian churches, sex has been seen in essence as a limited 'functional' activity, for procreation: any other forms of sexual activity were 'deviant', and to be condemned. This view of sexuality grew increasingly irrelevant for thinkers about sex, as Western societies experienced the enlightenment, the scientific revolution, and the development of modern knowledge about sex and sexuality. For the average practitioner, of course, it was always irrelevant.

But the churches became institutions of declining relevance in the modern world, even though their past animosities and eccentricities continue to exercise their hold. This decline in the authority of the Christian churches to interpret the world and the meaning of life unquestioned began with the emergence of scientific thought. As the authority of the church on sex and sexuality declined, the authority of a new group rose to prominence. This was the medical profession.

The medical profession

The medical profession's views on sex and sexuality – and on homosexuality in particular – were most important to the way in which western societies have perceived homosexuality over the twentieth century.

Homosexuality has obviously existed in all societies and over all of human history. But attitudes to homosexual behaviour have varied markedly across and between different cultures and through various historical periods. The changes in the 'social and subjective' meanings given to homosexuality are culturally specific: the various possibilities of same-sex behaviour are differently constructed in different cultures. [4]

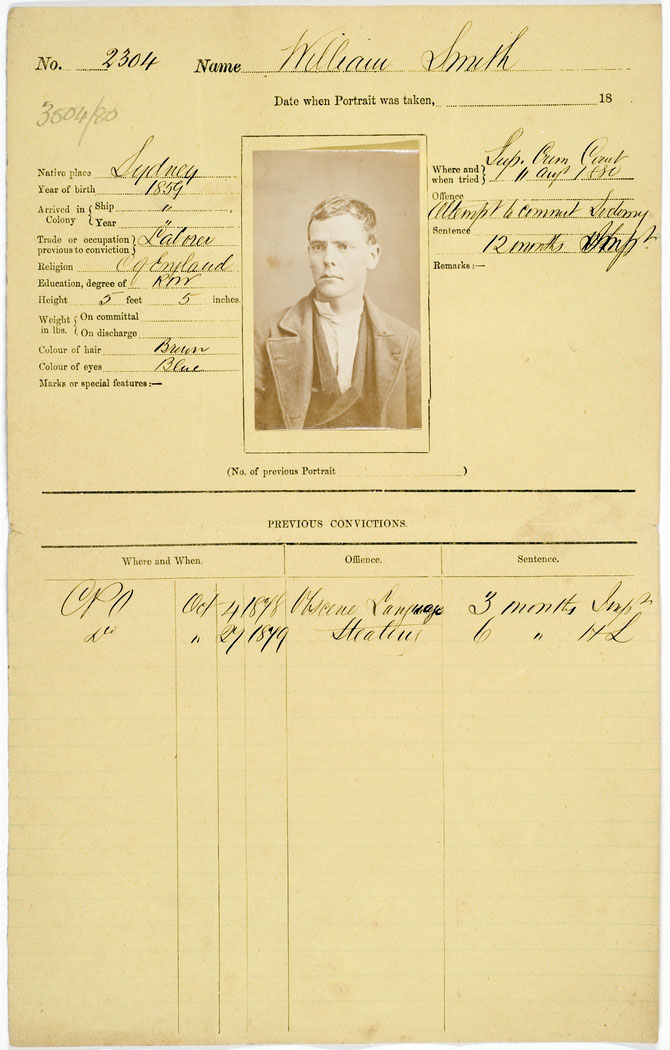

Sodomy in Sydney Town

Sydney has had a long association with homosexuality. Within a decade of the white invasion, the first cases were being reported. In 1796, the first trial for sodomy in Sydney took place: Francis Wilkinson was accused of buggering a fellow settler, but was acquitted. Over 30 years later, in 1828, Alexander Brown was the first person hanged for sodomy – a capital crime, as Governor Phillip had indicated. [5]

The apparent infrequency of prosecutions does not indicate either an absence of homosexual activity or a tolerant society. But it was a society that had some unusual features: it was a prison; men far outnumbered women for decades; and as a 'frontier' town, it was known for its looser-than-conventional moral arrangements.

These factors may help explain why so few cases of homosexual behaviour came before the courts, and how rarely the death sentence was carried out. But perhaps the answer also lies in the fact that, in a society existing largely outside the constraints of civilised behaviour, and with a death penalty attached, juries might have been reluctant to convict unless there was overwhelming evidence. Probably only in cases where force was involved – so that it was not a 'victimless' crime – or where a younger person was involved, were juries likely to convict.

The last person to be hanged in Sydney for sodomy was Thomas Parry, in 1839. Perhaps the push to end convict transportation encouraged the colonial justice system to show such an overt manifestation of 'civilised behaviour', particularly since England had itself recently abolished the death penalty for such acts.

Homosexual subcultures

Homosexual subcultures were emerging. Late in the 1830s, witnesses before a British parliamentary committee, The Select Committee …[on] Transportation and its Influence on the Moral State of Society in the Penal Colonies, tendered much evidence. Some commentators at the time suggested that the incidence of homosexual activity in the colony was exaggerated by these witnesses, to bolster their case for the cessation of transportation, but there is still a surprisingly wide range of indicators that homosexual activity flourished.

Witnesses told of men in the convict barracks in Sydney taking on female names – 'Kitty' and 'Nancy', 'Polly', 'Sally' and 'Bet' were all mentioned. They also told of the high prevalence of male physical homosexual activity in the colony: 'there were 100 cases in Sydney to [every] one in the United Kingdom'. Other witnesses told of same-sex 'couples' existing within the convict barracks. One magistrate told of a night visit to the convict barracks, and

on the doors being opened, men were scrambling into their own beds from others, in a hurried manner, concealment being evidently their object … I am told, and I believe, that upwards of 100 – I have heard as many as 150 – couples can be pointed out, who habitually associate for this most detestable intercourse, and whose moral perception is so completely absorbed that they are said to be 'married', 'man and wife…' [6]

And there were ongoing reports of 'unnatural crime', 'abominable behaviour', 'depraved and disgusting conduct' and 'atrocities of the most shocking, odious character'.

Class prejudices were aired as well: one witness declared that it was only a working-class vice, even among the convicts: 'among gentlemen convicts it would excite abhorrence!' [media]Sir Francis Forbes, the chief justice of the colony and a witness at the Select Committee, was reluctantly forced to acknowledge that Sydney 'had been called a Sodom in the papers', while denying the reality of these claims. [7]

Yet the establishment could exhibit ambivalent attitudes to what might be seen as unnatural behaviour. In 1835 a male convict, Edmund Carmen, was caught by police near Wollongong 'dressed in a woman's gown and cape'; he was found guilty of 'improper conduct' and given 50 lashes, and sent back to Sydney with the proviso that he was 'not to be assigned again to this District'. Yet some years later, when police arrested a woman for drunkenness in George Street and found that 'she' was in fact a man, they simply sobered him up and sent him on his way. Perhaps city dwellers, especially in a port city, were a more tolerant lot. [8]

Because there were no specific laws relating to same-sex sexual behaviour for women, records of such behaviour or identity are rarer. [media]But evidence occasionally surfaced, and it was predominantly within the population under control and scrutiny, namely the convicts in the female factories at Launceston, Hobart, and Parramatta. From records of these institutions, we know that 'unnatural intercourse between them is carried on to a great extent'. From another case, we also learn that the word 'nailing' related to women indecently 'using their hands with each others person'.

[media]But it was clearly a vice that was not confined only to the lower orders. In 1836, Sydney was rocked by the Reverend Yate scandal. This involved a protégé of the very respectable Samuel Marsden who was known as the 'flogging parson' for his penchant, as a magistrate, to hand out severe sentences as a deterrent. Yate was a well known and widely published preacher in England, who had even had an audience with King William IV. On the voyage out to Sydney on the Prince Regent, Yate had spent much time in the company – and the hammock – of the third mate, Edwin Denison. When they arrived in Sydney in June of that year, the two moved into lodgings together in Park Street, where they were joined by another sailor from the Prince Regent, with the unlikely name of Dick Deck. Neighbours soon complained about the men's behaviour, and the scandal became the talk of Sydney, although the Crown Solicitor suggested that 'it seems more than probable that the crime of sodomy cannot be proved against him according to law'. By mid-December of that same year, Yate and Denison had sailed for England, much to the relief of the Anglican community in Sydney. [9]

Gay love and affection

That homosexual behaviour was not confined to situational sex and could reflect emotional involvement and affectionate relationships is harder to verify, particularly given the paucity of relevant evidence – personal papers, such as diaries and letters, were often destroyed to protect 'the family name'. But when such evidence does surface, it is irrefutable. In 1846, a convict was executed, and among his possessions was found a letter for Jack, whom he addressed as 'Dear Lover'. In the letter he states that 'I value Death nothing, but it is in leaving you behind.' The letter's conclusion – 'I hope you wont fall in love with no other man when I am dead' [10] – is something that any lover might empathise with.

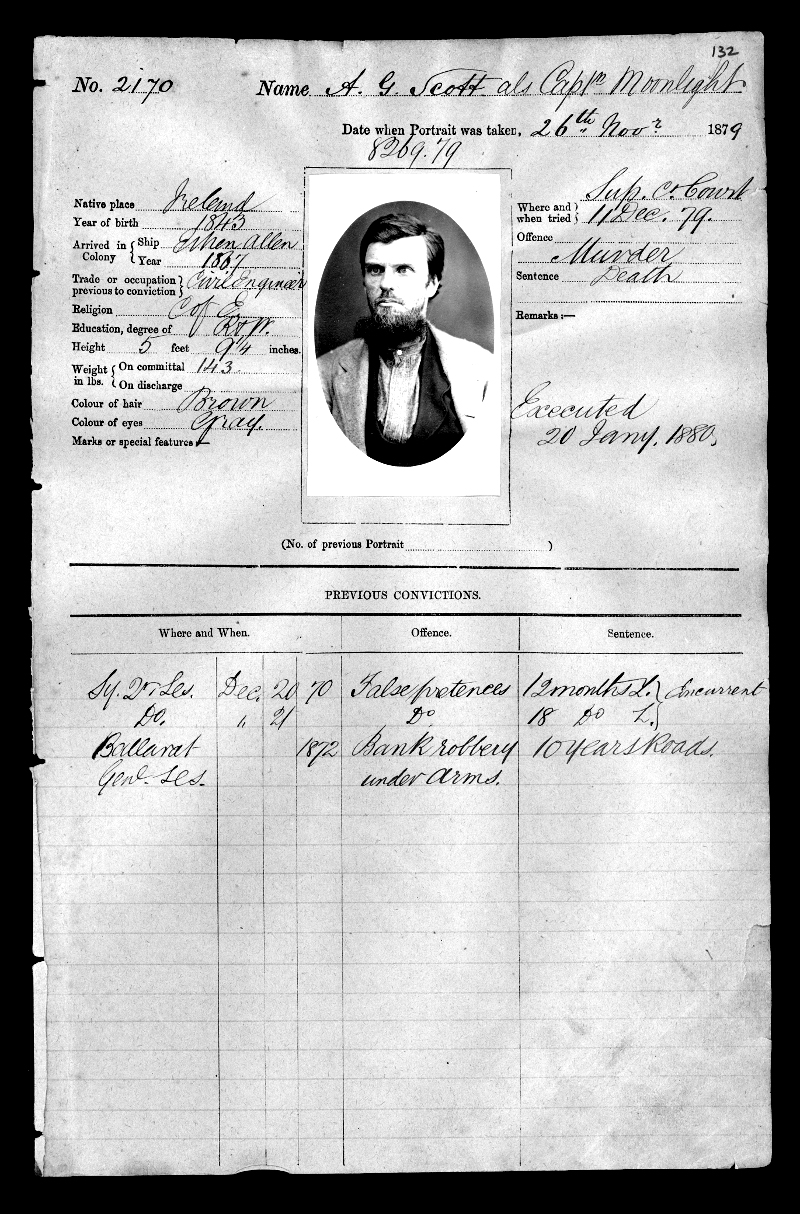

Perhaps the most famous case was of the notorious bushranger, Captain Moonlite (or Moonlight) and his publicly professed and overtly manifested love for his companion in crime, James Nesbit. [11]

[media]In 1879, when Moonlite – Andrew George Scott – was on trial in Sydney for his exploits, there was extensive newspaper coverage of both the trial and the events that had led up to it. Moonlite's gang had seized a sheep station in southern New South Wales, and in the ensuing shootout with the police, Nesbit was badly wounded. Heedless of the firing, Scott had lifted and carried the injured man into the house, where, as Nesbit lay dying,

his leader wept over him like a child, laid his head upon his breast, and kissed him passionately. [12]

Nesbit died on 17 November 1879.

While in his death-cell at Darlinghurst Gaol, Scott tried to make arrangements for his own burial after his hanging (which was to take place on 20 January 1880). The scandal was that he wanted to be buried in the same grave as Nesbit, and their tombstone was to tell it all:

This stone Covers the remains

of two friends

James P. N., Born 27/8/1858

Andrew G. S. Born 8/1/45

Separated by death 17/11/79

United by death 20/1/1880 [13]

Overseas [media]scandals involving homosexuality often reverberated in Sydney, particularly if they were at 'home', as Britain was often still regarded. Thus the Oscar Wilde trials in London in 1895 led local newspapers to consider whether Sydney might be similarly afflicted, and one newspaper, The Scorpion, discovered the 'Oscar Wilde's [sic] of Sydney'. It reported that 'this horrible vice is also the condition of affairs in Sydney', and went on to assert that 'it has been planted here by the English exiles…the men who escaped the Cleveland-street prosecution', [14] a reference to a scandal that had rocked Britain in 1889. It had been alleged by the London press that among the regular customers of a male brothel in Cleveland Street in London's Fitzrovia were several prominent aristocrats, including a son of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale and second in line to the throne.

Over the ensuing decades, scandals surrounding the homosexuality of public figures, such as the former Governor Lord Beauchamp, or the Director-General of the Department of Transport, Sydney Aubrey Maddocks, or the artist Douglas Annand, or the visiting Chilean pianist Claudio Arrau, continued to provide this sort of titillation in the popular press. [15]

Living a homosexual life

While little is currently known about 'women-focussed women' and their lives in the city, some figures have stood out. [media]One is Iris Webber, a gangster queen immortalised in the 'razor gang' wars which were a prominent feature of Darlinghurst in the 1920s, when it was the centre of the prostitution and cocaine rackets. Another was Des Tooley, 'the lady baritone', whose loyal fans and jazz lovers followed her at her various appearances over the 1930s.

While we know something about these public figures, how did the 'average homosexual' manage his life in these conditions? We do know that love and friendships existed well outside aristocratic circles. There were many places were like-minded men could meet. Over the years, cafes such as Mockbell's or Pellegrini's, or, later, Madame Pura's Latin Café, all had a reputation. Hotels, particularly those on the waterfront, like the Montgomery in Pyrmont or the ones in Woolloomooloo, or the so-called 'salt meat alley' bars along lower George Street, with their variety and ambiguity, were often places for less-than-discreet cruising. The Scorpion named a hotel in Bourke Street, Surry Hills as such a place. In the city itself, bars near theatres, or – somewhat later – the more middle-class hotels such as the Australia or the Carlton or Ushers, were all places where 'outsiders' could meet discreetly.

Outdoor meeting places or gay 'beats' (public places where men could loiter 'with intent') have always been popular. Public gardens, parks, esplanades near the sea, all have been used as such by homoerotically inclined men. As early as 1839, the Sydney Gazette had reported that 'The Domain is becoming a resort for very unproper characters of both sexes'. By the end of that century, Hyde Park near College Street was well known as a popular cruising area. With the opening of the new department stores on lower Oxford Street from the end of the nineteenth century, with their 'effeminate' sales clerks, and the proximity of the Turkish Baths – such as the one in lower Liverpool Street or Mr Wigsell's further up Oxford Street – Hyde Park remained a popular cruising place till well after World War II, when changed drinking hours encouraged the shift of homosexual social life out of the central business district. Nearby Kings Cross, already the city's 'bohemia', became home to many new gay venues.

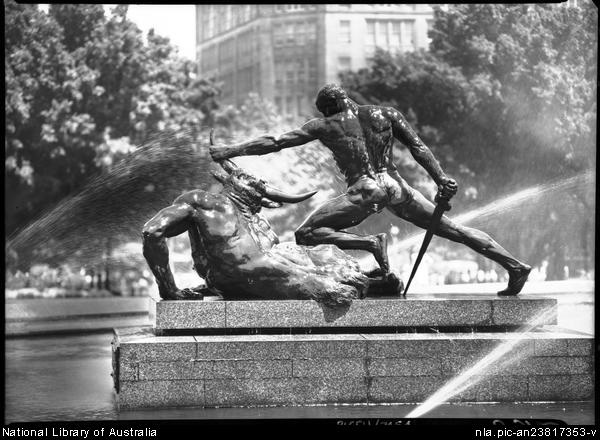

[media]That beats were reasonably well known is evident, mentioned even in popular novels: Christina Stead in Seven Poor Men of Sydney (1934) sets one such scene at The Gap near Sydney's South Head, while in Kylie Tennant's 1957 novel, Tell Morning This, the Archibald fountain was 'outed' as one of these cruising places.

But for those fearful of venturing too far into public view, friendship networks were the mainstay, an institution that kept any hidden subculture alive. And these have long been there. The 'memoirs' of Joe Chuck, an undercover policeman, tell us of the 'Queer House' near Wynyard, raided in 1917, where a coterie of young homosexual men lived. Chuck was amazed that, apart from their predilection for fancying other men, these men were virtually indistinguishable from the rest of the city's male population.

Perceptions of homosexuality

But change was in the air. From the late nineteenth century, there was ongoing debate about what homosexuality actually represented: were there 'causes' of homosexuality, and was it congenital or 'acquired'? This prefigured the debate between the nature and nurture schools of thought. The new field of 'sexology' was emerging, and writers such as Havelock Ellis, a one-time resident of Sydney, argued that nothing in nature proved that homosexuality was unnatural (indeed the opposite was the case), and that homosexuality was invariably congenital. Thus both moral censure and legal prohibition were inappropriate responses. His critiques made little short-term impact on public perceptions.

Ironically, the pendulum swung in the other direction when Freud in 1933 entered the debate. In Freudian theory, male homosexuality developed from an

unsuccessful resolution of the Oedipus complex: a boy became excessively attached to his mother, ultimately identified with her (rather than with his father), and then sought in male sexual objects substitute selves whom he might love as he had been loved by his mother. [16]

And although Freudian theory favoured the 'acquired' rather than the 'congenital', it was in the supposedly more neutral concepts of psychoanalysis, rather than in the overtly moralistic tones of Victorian thinkers: most of these had regarded homosexuality as an acquired perversion.

[media]In 1948 came the major bombshell of the Kinsey report. One of its most startling statistics – that 'more than a third (37 per cent) of white males in any population have had at least some homosexual experience' – meant, as Kinsey himself noted, that the laws relating to homosexual behaviour, if enforced, would lead society to fall apart. But he also argued that, because of this statistic, there are no 'homosexuals', but there is homosexual behaviour. This perception had implications in a debate that was generated some decades later.

Theory wasn't the only catalyst for change. [media]Wars, by necessity, created almost perfect conditions for strong homoerotic relationships to form; sex-segregation, and heightened emotions due to the fear of possible death, all encouraged the formation of strong personal bonds within the armed forces. And both World War I and World War II took thousands of young Australians, initially only men but increasingly women as well, away from their previous lifestyles and put them into a new 'emotional hothouse' situation. Certainly love and sex blossomed: during World War II, Patrick White, Australia's only Nobel Laureate for Literature, met his life-companion, Manoly Lascaris, with whom he returned to Sydney after the war.

Love in a Cold War climate

The impact of Kinsey's book had unfortunate results. Coming out in the early years of the Cold War, it frightened society's moral conservatives, leading to an irrational hysteria around homosexuality. [media]From the perspective of Catholic New South Wales Police Commissioner Colin Delaney, the two greatest threats facing Australia were communism and homosexuality. And the following decade saw numerous exposés of Sydney's homosexual subcultural life. Truth newspaper often published lists of names (given to it by the police) of people arrested at homosexual parties; there were high levels of police entrapment, with 'pretty young policemen' acting as agents provocateurs. [17]

Living in such a milieu brought the gay world into contact with the criminal world, most obviously in the surreptitious growth of gay bars from the early 1960s until decriminalisation of homosexual behaviour in 1984. This created the perfect conditions for corruption: Darlinghurst Police Station was commonly known as 'Goldenhurst' – rumour had it that no policeman was ever poor after he finished a stint at that station.

But hidden away from all this hysteria and persecution, the friendship networks flourished, and these were probably most important for women, who lacked both the economic resources and public acceptability that were available to men. Yet occasionally, details of 'passing women' – women who took on a male identity to live out a more fulfilling life – surfaced. The most notorious was Eugenia Falleni – 'sailor, husband, convicted murderer, boarding house madam', as she is remembered – whose exploits titillated respectable Sydney.

Postwar developments

Out of these friendship networks grew more formal social groups, which included lesbians and 'camp' men, as they were known: the groups' names – such as Chameleons and Diggers – tell of both the necessity for discretion and a common connection.

There were occasional amendments to the laws relating to male homosexuality in New South Wales over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The public responses they drew varied considerably. Amendments in 1924, lowering the penalty for buggery from life to 14 years imprisonment, drew little comment: they were seen as an acceptable movement away from the draconian penalties (for many crimes) of previous eras. By contrast, the major changes of the 1950s, to increase penalties and create new homosexual crimes, aroused major public debate. These latter changes should be seen in the political context of the times, when the 'communist menace' made any form of deviance seem of direct concern to authority in Australia.

The greater public awareness of homosexuality that this later debate created led to a major questioning of society's attitudes to homosexuality, and paradoxically played a role in uniting homosexuals and their supporters to fight oppressive laws and, ultimately, to changing community attitudes. Wider social changes – from the countercultural revolution of the 1960s to the social movements of the 1970s, and an increasing acceptance of Australia as a 'multicultural' society – were also important in reinforcing changing attitudes. Public opinion polls charted this new tolerance.

[media]One major development was a shift in location of the city's 'gay life'. Kings Cross was already home to aspects of subcultural life, but during the Vietnam war, R & R leave for US servicemen and the consequent growth of the drugs trade made Kings Cross a less attractive home to emerging gay life. The cheaper rents and lesser public focus on nearby Oxford Street led to its development as the new centre for the city's mainly male gay life, with a growth of a buoyant community, with its media, its clubs, sex venues, bars, restaurants, and other services. Suburbs such as Annandale and Leichhardt, fortresses of the women's movement, were seen more as home to emerging lesbian subcultures.

The rise of the gay movement

Within the changed social climate, it was possible for a politicised 'gay movement' to emerge. One of the major aims of gay political activism in New South Wales was law reform, and over the 1970s many campaigns were fought to achieve this. [media]There was little success despite an increasing number of confrontations – often violent – between the police and homosexual women and men. In 1982, the state government amended its Anti-Discrimination Act to extend protection to homosexuals. This created the situation where male homosexual acts were illegal under the state's criminal code, but all homosexuals could use anti-discrimination laws against institutions or persons in society who discriminated against them. It was an incongruous situation, eventually rectified in 1984, with the decriminalisation of male homosexual acts in the state. [18]

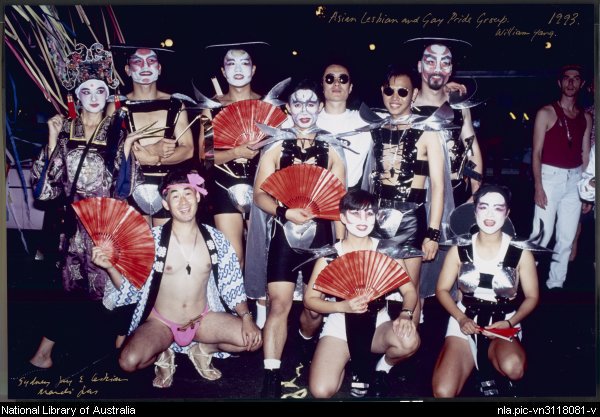

From the late 1970s, knowledge of Sydney's gay scene was thrust into public consciousness. This occurred first with the violent confrontation between police and marchers that occurred at the first Mardi Gras and the ongoing tensions played out in the city's courts. These moved many citizens to question both outdated perceptions of homosexuality and the role of the police in dealing with society's minorities. But within a few years, the impact of AIDS escalated public awareness of this subculture and its inhabitants even further. [19]

The growth of a politically active gay 'community' has had diverse results – the original rise of Clover Moore, state member of parliament and Lord Mayor of Sydney, has been attributed to her harnessing the gay vote in an electorate centred on Oxford Street, while capitalist Sydney was quick to embrace the opportunities offered by the so-called 'pink dollar'. In recent years there has been a residential dispersal of 'the gay community' away from the Oxford Street ghetto – the 'pink triangle' now extends from the inner east out to the inner west – but there is still a community, able to be mobilised when its rights and security are threatened. As one geographer has noted:

…'ghettoes' and psychic enclaves can potentially coexist with dispersion, just as there can be communities without propinquity. [20]

Identity and acceptance

There has also been a regeneration, within the wider gay community, of the debate about identity. In this, Sydney's homosexual population is similar to other groups in our multicultural society: what parts of our identity make us 'different' from, and in what ways are we 'the same' as, the wider Australian society? In the gay world, old ideas have once again emerged: are we what we are because of genes or 'social construction' – both of which have their truths. Identity is fluid, affected by the different historical circumstances that homosexually inclined women and men have found themselves in. [media]How such people have seen themselves in Australian society has varied quite considerably: from the 1920s, when, in the words of King George V, 'I thought men like that shot themselves', [21] to the 1950s, when 'camps' led lives that were still hidden but less isolated, to the openness of the late 1980s. The magnitude of such changed perceptions, over such a short period, is worth noting.

Minorities are defined by society through their difference. How far society tolerates or accepts difference varies over time. Today, the global context has all changed. [media]There is a now a worldwide 'gay' community – modern forms of communication, and the wider impact of ideas, all mean that perceptions of this difference are less detrimental to those of us who feel 'the love that once dared not speak its name'.

But complacency must not be allowed to obscure the fact that some fights are never over: there remain those who are vehemently opposed to such changes in the old social order. As Professor Bashir also warned:

So much has been gained over this period of greater enlightenment, but this must never be taken for granted. Most people would agree that across the world today, an extraordinary winding back to so many previously discarded attitudes is taking place. This regression not only impacts upon the rights of gay and lesbian groups, but also on women's health issues, and in some places on justice and legal processes. [22]

It should never be forgotten that the price of any freedom is eternal vigilance.

References

G Wotherspoon, 'City of the Plain' history of a gay subculture, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1991

C Faro, Street Seen: a history of Oxford Street, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2000

Notes

[1] Marie Bashir, Governor of New South Wales, Speech at official opening of the 2005 New Mardi Gras Festival Season, 4 February 2005

[2] Phillip to Sydney, 28 February, 1787, Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 1/2, pp 52–53

[3] RTE Latham, 'The Law and the Commonwealth', Survey of British Commonwealth Affairs, 1, 1937; V Windeyer, 'A Birthright and Inheritance: The Establishment of the Rule of Law in Australia', Tasmanian University Law Review, vol 1, pt 5, 1962, pp 635–69

[4] Jeffrey Weeks, Sex, Politics and Society: The Regulation of Sexuality since 1800, Longmans, London, 1981, p 110

[5] R French, Camping by a billabong: gay and lesbian stories from Australian history, Blackwattle Press, Sydney, 1993, pp 6–7

[6] Select Committee …[on] Transportation…[and] its Influence on the Moral State of Society in the Penal Colonies, British Parliamentary Papers, 1838; R French, Camping by a billabong: gay and lesbian stories from Australian history, Blackwattle Press, Sydney, 1993, pp 9–11

[7] Sir Francis Forbes, Minutes of Evidence, vol 1, p 30, 14 April 1837, Evidence to the Select Committee on…Transportation…[and] its Influence on the Moral State of Society in the Penal Colonies, British Parliamentary Papers, vol 19, 1837, p 518

[8] James Sheen Dowling, Reminiscences of a colonial judge, Anthony Dowling (ed), Federation Press, Leichhardt, 1996

[9] R French, Camping by a billabong: gay and lesbian stories from Australian history, Blackwattle Press, Sydney, 1993 pp 21–25

[10] R French, Camping by a billabong: gay and lesbian stories from Australian history, Blackwattle Press, Sydney, 1993, p 18

[11] G Wotherspoon, 'Moonlight and …Romance? The Death-Cell Letters of Captain Moonlight and Some of Their Implications', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 78, parts 3–4, December 1992

[12] Charles White, Short-lived Bushrangers, New South Wales Bookstall, Sydney, no date, p 24

[13] Letter from Scott to A McDonnell, 8 January 1880, in Letters of Scott and Rogan, Colonial Secretary's Special Bundles 4/825.2, 1889; State Records New South Wales

[14] R French, Camping by a billabong: gay and lesbian stories from Australian history, Blackwattle Press, Sydney, 1993, pp 43–44

[15] G Wotherspoon, 'City of the Plain' history of a gay subculture, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1991, pp 44–46, 123

[16] Paul Robinson, The Modernisation of Sex, Harper and Row, New York, 1972, pp 5–6

[17] G Wotherspoon, 'City of the Plain' history of a gay subculture, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1991, pp 112–24

[18] G Willett, Living out loud: a history of gay and lesbian activism in Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2000

[19] G Wotherspoon, 'History Lessons: Social responses to AIDS and other epidemics in NSW', in R Aldrich and G Wotherspoon (eds), Gay perspectives: Essays in Australian Gay Culture, Department of Economic History, University of Sydney, 1992

[20] IH Burnley, 'The geography of ethnic communities', in S Fitzgerald and G Wotherspoon (eds), Minorities: cultural diversity in Sydney, State Library of New South Wales Press in association with the Sydney History Group, Sydney, 1995, p 187

[21] Beverley Nichols, The Sweet and Twenties, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1958, p 101; Ted Morgan, Somerset Maugham, Jonathan Cape, London, 1980, p 549

[22] Marie Bashir, Governor of New South Wales, Speech at official opening of the 2005 New Mardi Gras Festival Season, 4 February 2005

.