The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Forest Lodge

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Forest Lodge

[media]The suburb Forest Lodge was named after a Regency villa designed by colonial architect John Verge for successful pharmacist Ambrose Foss in 1836. Three kilometres west of Sydney town, the seven room bungalow with verandahs was surrounded by an orchard, garden and elaborately landscaped grounds.[1]

Foss’s semi-rural retreat was located on shale-derived soils where 20m to 30m tall Turpentine (Syncarpia glomulifera) and Grey Ironbark (E.paniculata) trees grew along with Blackbutt (E.pilularis), Red Mahogany (E.resinifera), and White Stringybark (E.globoidea). Christmas Bush (Ceratopetalum Gummiferum), Sour Currant Bush (Leptomeria Acida) and Geebungs (Persoonia) were also part of the forest’s undergrowth.[2] This location suggested a romantic association with nature and notions of a leafy seclusion, and Foss named his house after its idyllic woodland setting.

First people

The Gadigal and the Wangal bands of the Eora people were living in the Forest Lodge area long before European occupation and continue to be its traditional custodians. Aboriginal archaeological sites are often associated with features like freshwater creeks and rock platforms,[3]and the remnant salt marshes fringing the lower parts of Orphan School and Johnstons Creeks have yielded middens of ark cockles (Anadara trapesia), Sydney rock oysters (Saccostrea cuccullata), scallops (Pecten fumatus) and Mud Welks (Pyrazus ebeninus).

Age of Villas

Timber felling and farming along the banks of Orphan School Creek (originally called Grose Farm Creek), along with sandstone quarries along modern day Ross Street, were some of the earliest industries in Forest Lodge.[4] Prosperous Sydney merchants and professionals were attracted to places like this just beyond the urban perimeter, and their picturesque villas, fashioned from nearby brick pits and quarries, were soon set back in spacious grounds on either side of the route which would become Pyrmont Bridge Road.

By 1845 five villas – Forest Lodge, Rose Cottage (built in 1838), Oak Lodge (1836/7), Enfield House (1843) and the Willows (1845) – dotted the Forest Lodge landscape.[5] “The private residences of the richer class of gentry”, wrote CJ Baker in 1845, “are also a little removed from the town and are very surprising from their number and costliness”.[6]

The economic recession of the 1840s slowed the rate of construction, but as prosperity returned in the 1850s a new wave of families found havens in picturesque retreats – Kayuga (later Jarocin) was built in 1857, followed by Briarbank in 1863, Braeside Cottage in 1864, Cloyne Lodge in 1865, The Hermitage in 1866 and Reussdale in 1867.[7]

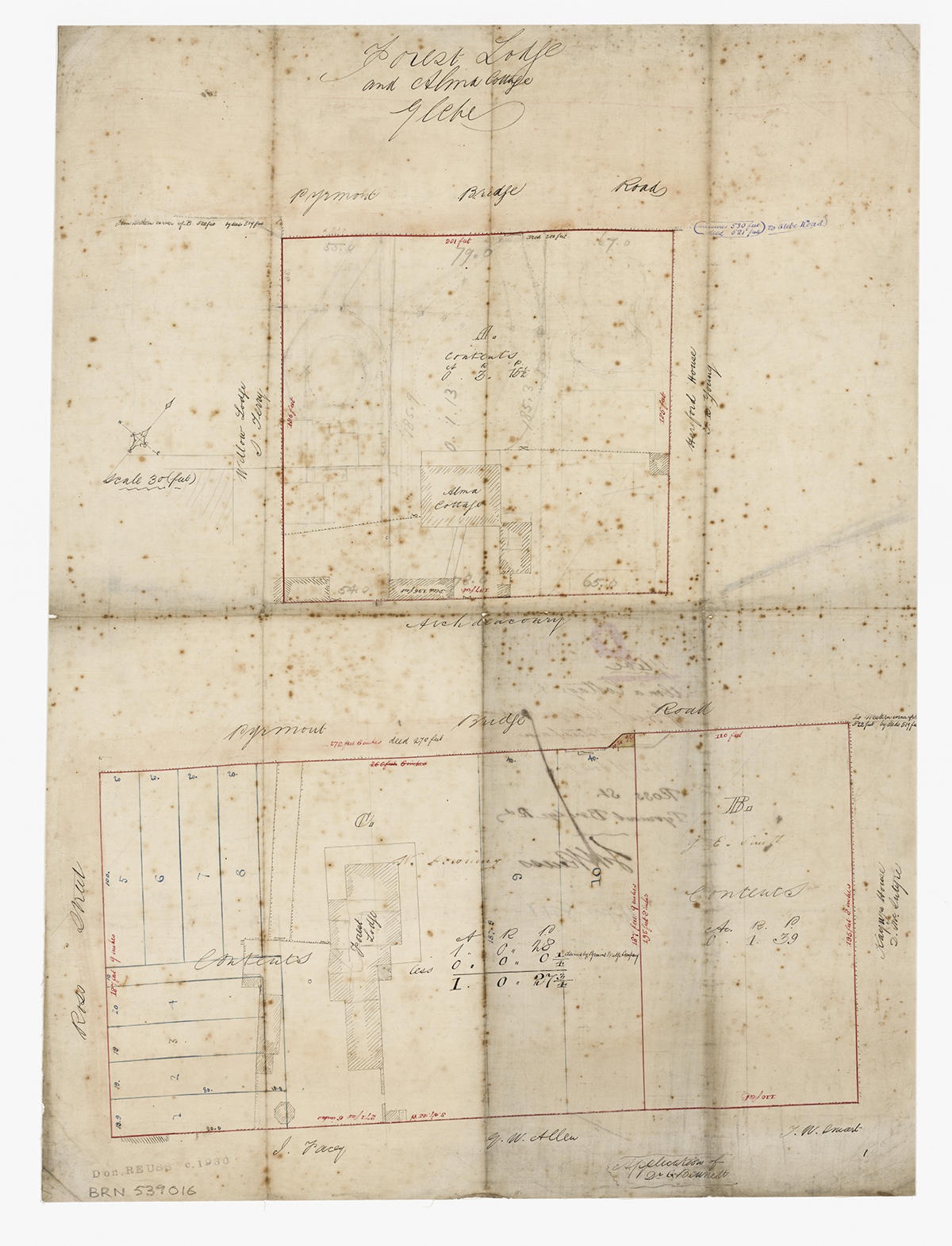

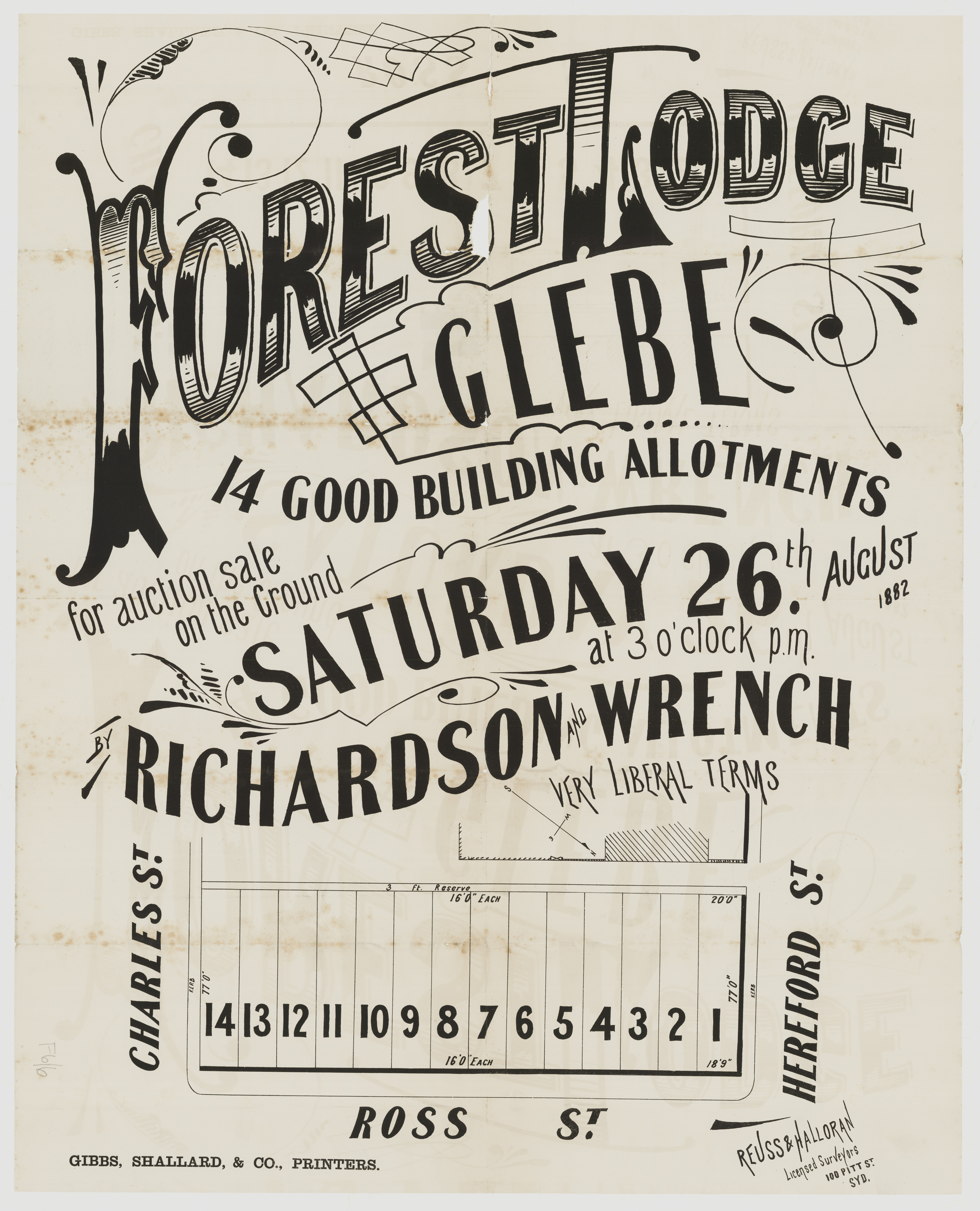

A second phase of property development began in 1865, triggered by the subdivision of the forty five acre (18 hectares) Forest Lodge Estate by a consortium of land owners, George Wigram Allen, Randolph J Want, Thomas Holt and Thomas Ware Smart.[8] The process of building up and peopling the streets of Forest Lodge had begun.

Terrace housing

[media]From the 1870s, new building techniques that offered an economy of outlay on land and materials ushered in the single and two-storeyed terraces that have left an indelible imprint on the suburb’s architectural character.[9]The scale of terrace development was most pronounced along its main arteries, Pyrmont Bridge Road and St Johns Road.

Forest Lodge’s terrace builders often operated precariously, financing their ventures with serial mortgages. Between 1877 and 1883 Andrew McGovisk constructed twenty two separate dwellings in three terraces, ‘Avoca’, at 7-15 and ‘Auburn’ at 17-31 Junction Street and around the corner ‘Magnolia’ at 272-280 Bridge Road. He then sold each completed terrace rather than leasing it.[10]

The casual observer can distinguish several terrace types on the Forest Lodge landscape – for example, the single storey Italianate dwellings at 33-53 Charles Street, the verandah and balcony of Hollyhock terrace at 32-38 Lodge Street, Rowe’s Terrace’s cantilevered balcony at 146-156 St Johns Road, and Cliff Terrace’s bay window that overlooks the former Harold Park.[11]

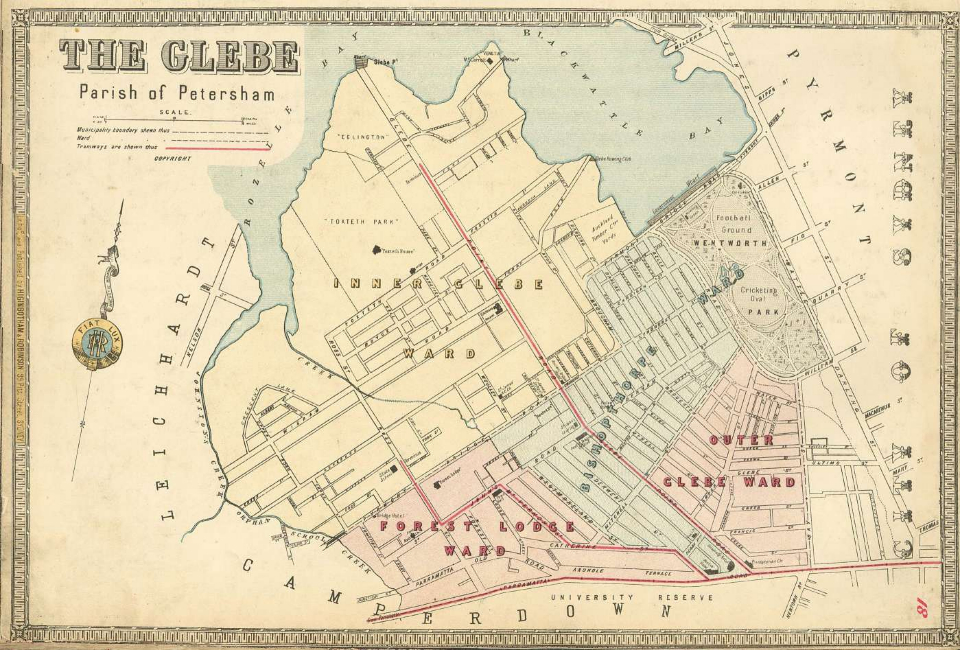

The Forest Lodge ward

By 1870 residents felt neglected by Glebe Council, and on 14 April ratepayers petitioned the Council to take steps to create a separate territory to be known as Forest Lodge ward.[12] Architect and Glebe alderman William Munro proposed that the new ward should include the Forest Lodge Estate together with the portion of Grose Farm that lay between old Parramatta Road (now Arundel Street) and new Parramatta Road,[13] and support for this suggestion led to the creation of Forest Lodge ward in February 1871.[14] [media]The official limits and boundaries of the new Forest Lodge ward set by Council gave the area its own unique character. The ward extended from Orphan School Creek along Parramatta Road, briefly entering Derwent and Catherine Streets, and then followed Westmoreland Street across St Johns Road and down Purves Lane, Hewit Lane and back travelling west along Bridge Road to Orphan School Creek. [15]

The new ward was first represented on Glebe Council from 1871 by three elected representatives, timber merchant John Seamer, boot manufacturer Joseph Davenport and general dealer George Williams.[16] Seamer was a Forest Lodge man in the best parish pump tradition and the archetypal self-made man who told a gathering he arrived in Sydney from England in 1855 “with only my head and hands to make a living”.[17] As mayor in 1878 he made sure the site for a new town hall was in his ward, and ballasting of St John’s Road was given priority during his mayoralty.[18]

By 1891 Forest Lodge accommodated 2,554 people in 539 dwellings.[19]

Local politics

For its first sixty five years Glebe Council was dominated by ‘self-made men’. The property-based system of plural voting ensured the majority of the total population (without property) were excluded from the suffrage, and absence of payment generally made it inaccessible to wage and salary earners.[20] It was also exclusively male and predominantly Protestant in composition to 1918 (only 3 of 85 were Catholic).[21]

As the suburb became increasingly industrial and working class, the introduction of the adult franchise enabled the Labor Party to wrest control of the Council from businessmen, and in 1925 the blue flannel shirt, rather than suit and tie, became the favoured dress.[22] The majority of Labor councillors were Catholic, explicitly anti-Communist, socially conservative, and committed to social welfarism with strong links to the union movement.

Albert James ‘Bert’ Ward was elected an alderman on Glebe Council from 1925 to 1939, and became Deputy Mayor in 1928. As Mayor in 1931 he established a soup kitchen at Glebe Town Hall under the Glebe Unemployment Relief Fund, and was involved in protests against Scullin’s government pension cuts.[23]

In 1947, under Mayor Cornelius O’Neill, Glebe Council began an enlightened project to construct 18 cottages in Forest Lodge with council labour and sold them to local renters at cost through a public ballot.[24] Much of the hard work in Forest Lodge’s Labor branch was done by women, but they were generally not rewarded by representation on Council. Their auxiliaries and distress societies formalised and gave recognition to informal networks that had existed for decades.

At the local branch level in the 1970s and 1980s, left wing intellectual politics mounted a challenge. The Forest Lodge ALP branch was dominated by the extended family connections of Les McMahon, a fiefdom notoriously difficult to join. Exclusion of factional opponents was a feature of this period and characteristic of the turbulent and factious nature of local branches.[25]

The Communist Party of Australia’s newspaper the Tribune was printed at 21 Ross Street in Forest Lodge from 1943 until 1976[26], along with other left wing publications like women’s liberation posters, anti-Vietnam War materials, leaflets, Tharunka, and books, for example Katharine Susannah Prichard’s Why I am a Communist. The printing works was raided by Commonwealth security police in 1949 and 1953.[27]

People

Prominent colonial citizens of the Forest Lodge community included James Barnet, Colonial Architect 1865 to 1890, who resided at Braeside Cottage near the junction of Ross Street and Parramatta Road for forty years[28], retailer David Jones, architects FH Reuss Snr and FH Reuss Jnr, Michael Chapman of Cloyne Lodge who was the Mayor of Sydney in 1871/72 and Mayor of Glebe from 1882-84, and architect William Munro and his surgeon son, also William.

Other local characters included, Bill ‘the Boss’ Bardsley, headmaster of the Forest Lodge School for 38 years,[29] parish priest Patrick Coonan, Primitive Methodist lay preacher Henry Carruthers, James Cummins, the No 1 soldier of the Salvation Army troop from 1885 to 1923,[30]and chemist Orion Leggo who was remembered in the inter-war years for providing advice to those in need of medical care, but unable to afford the doctor’s fee.[31] At Forest Lodge Methodist church, Ellen Carruthers and Lillian Morgan engaged in voluntary work for fifty years and in the Salvation Army, Ida Wilmot, Florrie Tomlin and Jessie Ford were remembered for lives of remarkable voluntary work.[32]

Tennis player Lew Hoad lived at 43 Wigram Road from 1938 and grew up visiting the local Police Boys Club and playing tennis on local courts. The reserve on Minogue Crescent that was originally part of Allen’s Bush was renamed in Hoad’s honour in 1965.[33]

Community

In the 1860s enterprising providores, including butchers, bakers and grocers, appeared in the suburb, relying on the patronage of a relatively small but concentrated clientele. [34]

Pubs, churches and schools also sprang up to meet other local needs. The Old Forest Lodge Hotel on the corner of St Johns Road and Lodge Street was the first public house and opened for trading about 1865, with proprietor John Tucker also operating as a butcher.[35] Later it was known as the Town Hall Hotel and then the Nag’s Head.

Pubs played a central role in the working class culture of the suburb. They were an important public space for socialising and discussing suburban life, and a forum for all sorts of meetings. Residents tended to patronise drinking outlets closest to home – the Forest Lodge, Durrell’s, British Lion, Bridge and Centennial, each competing for business.

Competing for the souls of the masses were church and chapel and strong local networks were built around the places where residents worshipped, educated their children and sought fellowship. [36] Forest Lodge developed a strong nonconformist presence led by Congregationalists, Primitive Methodists and the Salvation Army, all with established places of worship and their own social cachet.[37] Life for Catholic residents in Forest Lodge parish centred on the nuns and brothers of St James church in Woolley Street from 1877.

In 1883 the government constructed a new public school at Forest Lodge, providing a basic education in literacy and numeracy for a burgeoning populace. Enrolments increased from 492 in 1883 to 1,038 at the end of the nineteenth century.[38] In 1913, as part of the embryonic kindergarten movement,the Sydney Day Nursery moved from Darlington to 24 Arundel Street which was ‘more suitable in every way […] for the accommodation of the little mites while their mothers were out working’.[39]

While there was a mix of socio-economic groups in Forest Lodge, as indicated by the different kinds of houses, the majority of residents lived in modest circumstances. Tenancy of housing at Forest Lodge remained the predominant practice until the Second World War and beyond; 84% were tenants in 1891, rising to 88% at the 1933 census.[40]

The neighbourhood in Forest Lodge offered families the chance to piece together the social fabric they needed in order to exist with some measure of security, embracing, as they did, the values and practices of neighbourliness and mutual aid.[41]

Glebe Town Hall

Between 1880 and 1948 the Glebe Town Hall on St Johns Road was Forest Lodge’s most important public space; a forum for public meetings, friendly society and Masonic functions, concerts and musical evenings, theatricals, dances, church services and court sessions as well as the centre of local administration and a site for demonstrations.

Its function changed with political boundaries and as Glebe came under the City of Sydney’s administration in 1949, and then Leichhardt Council from 1968 when the Glebe neighbourhood centre offered an array of community-based activities there. In 2003 Glebe again became part of the City of Sydney Council, and in 2013 the town hall was extensively renovated and re-opened in March 2013.

Transport

Early residents walked everywhere in Forest Lodge, especially housewives, children and old people who were closely tied to their neighbourhood. Transport, in the form of the horse bus with its sixpenny fare in 1864, was initially beyond the means of working folk, but by 1872 intensity of horse bus competition reduced the fare to 3d.[42] Forest Lodge bus services, with their own destination sign, provided passengers with a wide area of coverage, stopping frequently. Horses also remained important for personal mobility and Glebe local government area housed 963 of them in 1892.

[media]Steam tram tracks were extended to the precinct in 1884, further stimulating residential growth [43] but the horse bus, running at six minute intervals in 1887, continued to hold its own against the twopenny tram journey into the city [44] until the advent of the subsidised penny tram in 1900. The tram network was shut down on 23 November 1958 [45] and the 470 bus that runs through Forest Lodge in 2018 continues to follow the original tram route.

Harold Park: the ‘red hots’ and the dogs

In 1890, the modest Lillie Bridge pony rack track opened at the bottom of Wigram Road. This was a distinctly working class activity, with its short course, cheap admission fees and bookmakers willing to lay a penny bet.[46] Even after several name changes, the track remained very much in the pre-modern sporting mould until the formal advent of night trotting on 1 October 1949 heralded the sport’s transformation to a modern industry.[47]

Promoted as glamorous and exciting, the NSW Trotting Club at Harold Park endeavoured to foster a nightclub atmosphere – lights and luxurious facilities, and opportunities for gambling when stars like Cardigan Bay and Paleface Adios ‘raced under the stars’. Crowds rose dramatically to a record attendance of 50,346 in 1960.[48] The Harold Park hosted the Inter Dominion harness racing at intervals from 1952, and from 1967 its annual signature event was the Miracle Mile.[49]

The eventual retreat of mainstream racegoers to TAB shops, hotels and social clubs meant the crowds of yesteryear at Harold Park ‘red hots’ (trots) vanished and the final race meeting was held there on 10 December 2010.[50] Its closure released 10.6 hectares for redevelopment by Mirvac with 3.8 hectares as open space. The development of about 1,250 apartments and units up to eight storeys high, and the opening of the food hall in the converted 1904 tramsheds in 2016, provided a new population of about 2,500 people.

It was also at Harold Park that Mechanical Hare Greyhound Racing began in Australia on 28 May 1927.[51] By July crowds were reaching 30,000, and it rapidly became the premier greyhound track in NSW, remaining so for the next sixty years. [52] In the 1950s and 1960s crowds averaged 7,000 to 8,000 per meeting but again, betting on the off-course TAB meant fewer punters attended the track. [53]

Harold Park, the Mecca of greyhound racing, hosted their final meeting there on 21 September 1987. Metropolitan greyhound racing had alternated on Saturday nights with Wentworth Park in Glebe from 1950, which after 1987 became the sole premier metropolitan track. ‘The dogs’ had its own unique atmosphere, and its spirit endures in the minds of those who passed through the Harold Park turnstiles as a significant part of Sydney’s social and cultural life.

Industry

Before 1869 industry in Forest Lodge was, apart from its quarries and 1830s brickpits, conspicuous by its absence, but eventually businesses, large and small, began to penetrate the neighbourhood. The miscellaneous collection of enterprises included the Fludders steam joinery that opened in St Johns Road in 1880, and the manufacturers of biscuits (Hackshall 1891, Arnotts 1901), jams (Lackersteen 1895), macaroni (Vi Vivaldi 1903) and confectionery (Aurousseau 1891) that had premises along Parramatta Road.[54] In Albert Street sculptor Nelson Illingworth established the Denbrae Terra Cotta Works c1894 to 1898 to manufacture flower pots, fern pots and statuettes and ceramic portraits [55]

Other local industries included Lanham’s laundry that opened in 1903 and coachmaker GH Olding & Son who set up shop in 1912 and by 1915 had adapted his enterprise to making military wagons for the AIF. In 1912, the Melocco Brothers moved from Redfern to premises on Parramatta Road where they continued their fine work in marble, mosaic and terrazzo until moving to Annandale in 1919. McArthur’s three storey straw hat factory opened on Junction Street in 1900.[56]

In 1927, a larger scale enterprise, lead works & building supplies business GE Crane moved into Ross Street, followed in 1932 by manufacturing engineers C&C Engineering on Bridge Road. Small mechanical and general engineering workshops, together with printing firms and other comparable types of small businesses were also attracted by Forest Lodge’s cheap rents and ready access to the city.[57]

The largest employers in Forest Lodge in 1945 were the Rozelle Tramway Depot with 650 staff, GH Olding & Son with 400, GE Crane with 300, C & C Engineering with 250 and Harold Park with 115. Overall there were 156 factories in the Glebe municipality, employing 4,496 people by 1945.[58]

By the 1980s, the decline of inner city manufacturing, and deindustrialisation of the metropolitan labour force rendered most of these industrial facilities obsolete, and many of the old premises were demolished or converted.

Demographic change

Non-British migration to Sydney in the early post-war years led to a much more diverse community in Forest Lodge, which, with its low rents and proximity to work and the city, was appealing to new migrants.

Sandra (Andriana) Kafataris arrived in Forest Lodge in 1958 from a small village near Larnaca in Cyprus. In about 1955, Savvas, Sandra’s husband, had acquired premises at 46 Ross Street and here they ran a fruit and vegetable shop. The family lived above the shop where they worked seven days a week, 16 hours a day, closing at 10pm from 1960 to 2011. The Kafataris thought of their customers ‘like neighbours’ and introduced them to new vegetables and ingredients that had not been part of the local Anglo cuisine, like garlic, eggplants, capsicums and zucchini.

The Forest Lodge tenantry, largely undisturbed for three quarters of the twentieth century, shifted as industry declined and the area started to become fashionable with new, more affluent residents. The proximity of the University of Sydney also meant that increasingly students were establishing share houses, while academics and other professionals were occupying houses that had formerly been tenanted.

This period of diversity and gentrification was reflected in the number of restaurants that sprang up, a new and unique infrastructure of consumption. The Mixing Pot, an Italian restaurant at 178 St Johns Road, was a popular meeting place from the 1970s and remembered for the introduction of its specialty dessert, tiramisu.[59] Others businesses in Ross Street included a Greek Cypriot Deli, Chinese takeaway and, from the 1980s, a Vietnamese restaurant.[60]

Some Forest Lodge pubs, anxious to create a new image, dispensed with their old names, and were extensively renovated to cater for a more affluent clientele.[61] Others, a little proud of their long Bohemian connection, largely remained in the traditional mould.[62]

The Drill Hall on Hereford Street which had strong associations with AIF enlistments, the Army Reserve and as a polling place was replaced by town houses in the late 1990s while the building at 191 Bridge Road that housed the Working Men’s Institute and School of Arts from 1923 to 1955 and then the Glebe branch library between 1956 and 1995 was redeveloped as apartments at the same time.

At the 2016 census 4,563 people lived in Forest Lodge, a substantial increase on the 1891 figure of 2,554 and with an occupational composition very different from the working classes of yesteryear: 45.9% professionals, 16.4% managers, 11.8% clerical and administrative workers and 8.3% community and personal service workers.[63]

The obliteration of familiar landmarks and significant sites in neighbourhoods undergoing transformation, whether through demolition or use conversion, is often deeply felt and changes the character of a suburb, and Forest Lodge has been no exception to this process.

References

Notes

[1] Forest Lodge: To Let, Sydney Morning Herald, 10 March 1848, 4

[2] C.Burton, McDonald McPhee Pty Ltd, ‘Landscape Heritage’, Leichhardt Municipality Heritage Study, Vol 1, Sydney : Leichhardt Municipal Council, 1990, 90-92

[3] RJ Lampert, ‘Aboriginal Life Around Port Jackson 1788-1792’, in B Smith and A Wheeler (eds) The Art of the First Fleet and Other Early Australian Drawings, Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1988, 19-69

[4] Rosemary Kerr; The Physical development of Buildings and Grounds, University of Sydney Grounds Conservation Plan, October 2002, Appendix A: Overview History p A16, University of Sydney website https://sydney.edu.au/content/dam/corporate/documents/about-us/campuses/grounds-conservation-plan-appendices.pdf viewed 24 April, 2018; Supreme Court, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 5 May, 1832, 2

[5] B Dyster, Servant and Master: Building and Running the Grand Houses of Sydney 1788-1850, Sydney: University of New South Wales, 1989, 48

[6] CJ Baker, Sydney and Melbourne, London: Smith, Elder & Co, 1845, 135

[7] Michael Foster and Max Solling, “A Semi-Rural Retreat”, Places, People and Society in Glebe 1828-1861, Pt 1 Leichhardt Historical Journal, No 23, 2002, 5-15

[8] Land Titles Office Roll Plan 733 & 4022 (L) Conveyances Book 80 Nos 832-834

[9] R.Jackson, Owner Occupation of Houses of Sydney 1871 to 1891, Australian Economic History Review, Vol 10, No 2, 1970,138-154

[10] Certificate of Title, Volume 274 Folio 101, DP 2875; Land Titles Office Mortgage Nos 20149; 23870

[11] Bernard & Kate Smith, The Architectural Character of Glebe, Sydney: University Co-operative Bookshop, 1973

[12] Sydney Morning Herald 31 March 1870, 4

[13] Sydney Morning Herald, 11 May 1870, 5

[14] Sydney Mail, 2 April 1870, 14

[15] The Glebe, Parish of Petersham, Atlas of the suburbs of Sydney. Part 1 / compiled from the latest official and authentic private sources, Sydney : Published by Higinbotham, Robinson & Harrison, draughtsmen, lithographers & map publishers, [1886?]

[16] Sydney Morning Herald, 10 February 1871, 1

[17] Sydney Morning Herald, 22 March 1882, 5

[18] Sydney Morning Herald, 19 February 1878, 6

[19] TA Coghlan, General Report of Eleventh Census of New South Wales, Sydney: D Potter, NSW Government Printer, 1894

[20] A.J.C. Mayne, A Most Pernicious Principle : the Local Government Franchise in Nineteenth Century Sydney, Australian Journal of Politics & History, vol 27 (1981), 160-171

[21] Max Solling, ‘Biographical Register of Glebe Councillors’, unpublished.

[22] Michael Hogan, Local Labor. A History of the Labor Party in Glebe 1891- 2003, Leichhardt: The Federation Press, 2004, 77-85

[23] Max Solling, ‘Biographical Register of Glebe Councillors’, unpublished.

[24] Michael Hogan, Local Labor. A History of the Labor Party in Glebe 1891- 2003, Leichhardt: The Federation Press, 2004, 149

[25] Michael Hogan, Local Labor. A History of the Labor Party in Glebe 1891- 2003, Leichhardt: The Federation Press, 2004 183, 217

[26] Trib's on the move -- to new offices & $20,000 target, Tribune, 12 November 1974, p2

[27] Police Raid Printery Of Communist Paper, Sydney Morning Herald, 13 July 1949, 1; Summons on three as raid’s sequel, The Sun, 31 July 1953, 1

[28] DI McDonald, James Barnet – Colonial Architect, Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, 55 (1969), 124-140

[29] Max Solling, William Bardsley:’The Boss’ of Forest Lodge School, Leichhardt Historical Journal, No 9, 1980, 18-20

[30] John Fletcher and Michael Hogan, St James' Parish, Forest Lodge: 125 years : 1877-2002, Forest Lodge: Michael Hogan, 2002; H Carruthers, Rehoboth Methodist Church, Forest Lodge. A Short History, Sydney: Rehoboth Methodist Church, 1923; Max Solling, The Salvation Army in Forest Lodge, 13 September 1997, Salvation Army – Forest Lodge Corps History Book

[31] Sands' Sydney and suburban directory, 1903 to 1932; Max Solling, Hoad, Lewis Alan (Lew) (1934-1994), Australian Dictionary of Biography website http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hoad-lewis-alan-lew-18994 viewed 20 June 2018

[32] Max Solling, The Salvation Army in Forest Lodge 13 September 1997, Salvation Army – Forest Lodge Corps History Book, 5

[33] History of Lewis Hoad Reserve, City of Sydney website, http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/learn/sydneys-history/people-and-places/park-histories/lewis-hoad-reserve, viewed 23 April 2018

[34] Sands' Sydney and suburban directory, 1871

[35] Sands' Sydney and suburban directory, 1865

[36] John Fletcher and Michael Hogan, St James' Parish, Forest Lodge: 125 years : 1877-2002, Forest Lodge: Michael Hogan, 2002

[37] Max Solling, The Glebe Congregational Church, Leichhardt Historical Journal, No 5, 1975, p19-22; Max Solling, Methodism in Glebe 1841-1977, Leichhardt Historical Journal, No 18, 1993, 3-12

[38] Forest Lodge Primary School website http://www.forestlodg-p.schools.nsw.edu.au/our-school/history viewed 22 June 2018

[39] Day Nursery: New Premises Secured, Sydney Morning Herald 30 August 1913, 4; Day Nursery Association: New Premises Opened, Daily Telegraph, 3 June 1914, 13

[40] RV Jackson, ‘Owner Occupation of Houses in Sydney 1871 to 1891’, Australian Economic History Review, Vol 10 No 2, 1970, 148

[41] Michael Gilding, The Making and Breaking of the Australian family, Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1991, 31- 47

[42] Bradshaws Almanac 1864, Sydney: Henry Woolley, 1864,17

[43] RK Willson, RG Henderson, DR Keenan, The red lines : the tramway system of the western suburbs of Sydney, Sydney: Australian Electric Traction Association, 1970, 7

[44] Sydney Morning Herald, 2 February 1887, 13

[45] RK Willson, RG Henderson, DR Keenan, The red lines : the tramway system of the western suburbs of Sydney, Sydney: Australian Electric Traction Association, 1970, 86

[46] Referee, 1 January 1890,1,3; A.Paterson, Off Down the Track: Racing and other yarns, North Ryde: Angus & Robertson, 1981, 154

[47] Greg Brown, One Hundred Years of Trotting 1877-1977, Sydney: Whitcombe & Tombs, 1981, 193

[48] Big Trots Crowd Runs Wild, The Sun Herald, 14 February 1960, p1; John O’Hara, ‘Horse Racing & Trotting’ in W Vamplew & B Stoddart (eds), Sport in Australia: A Social History, Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 1994, 93-111

[49] Bob Cain, Harnessing a Miracle: The Miracle Mile Story, Kilmore, Vic: Bob Cain, 1990

[50] Sydney Morning Herald 13 December 2010, 8

[51] Referee,1 June 1927,15

[52] Sporting Globe, 20 July 1927, 7

[53] Sydney Morning Herald, 20 April 1985, 76

[54] Sands' Sydney and suburban directory, 1865, 1869 1871, 1880,1886, 1889, 1891, 1895, 1901; NSW Statistical Register, Sydney: NSW Govt. Printer, 1880-1888

[55] Australian Star, 6 February 1896, 5

[56] Weir Phillips Heritage, Heritage Assessment, 232 Junction Street, Forest Lodge, Woolloomooloo, 2017, p24 City of Sydney website Central Sydney Planning Committee, 30 November 2017, Item 13, Attachment A2 https://meetings.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/Data/Central%20Sydney%20Planning%20Committee/20171130/Agenda/171130_CSPC_ITEM13_ATTACHMENTA2.pdf viewed 24 April 2017

[57] Glebe including Forest Lodge, Wise's New South Wales post office directory, Sydney: Wise's Directories,1936, 226-229

[58] New South Wales Year Book 1945/46, Sydney: Australian Bureau of Statistics. New South Wales Office, 1946, 6178

[59] David Dale, Food for thought in a culinary evolution, Sydney Morning Herald, 12 July 2005, Sydney Morning Herald website https://www.smh.com.au/news/opinion/food-for-thought-in-a-culinary-evolution/2005/07/11/1120934184169.html, viewed 22 June 2018

[60] Sandra (Andriana) Kafataris, Personal interview 27 June 2015 with Max Solling and Helen Randerson

[61] Jock Collins and Antonio Castillo, Cosmopolitan Sydney, Leichhardt, NSW: Pluto Press, 1998, 62; Sian Powell, The working man battles the tide of boutique beer, Sydney Morning Herald, 29 September 1990, 19

[62] Sian Powell, The working man battles the tide of boutique beer, Sydney Morning Herald, 29 September 1990, 19

[63] 2016 Census QuickState Forest Lodge, Australia Bureau of Statistics Census website http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/SSC11546 viewed 24 April 2018