The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Devonshire Street Cemetery

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Devonshire Street Cemetery

[media]Sydney’s Devonshire Street Cemetery, as it has come to be known, was a cemetery of firsts. Not only was it the first time the Surveyor-General grouped a set of burial grounds together; Devonshire Street was also the first time attempts were made to regulate burials and order the cemetery landscape. In use from 1820 until the 1860s, it was Sydney’s second major cemetery.

Seven separate burial grounds

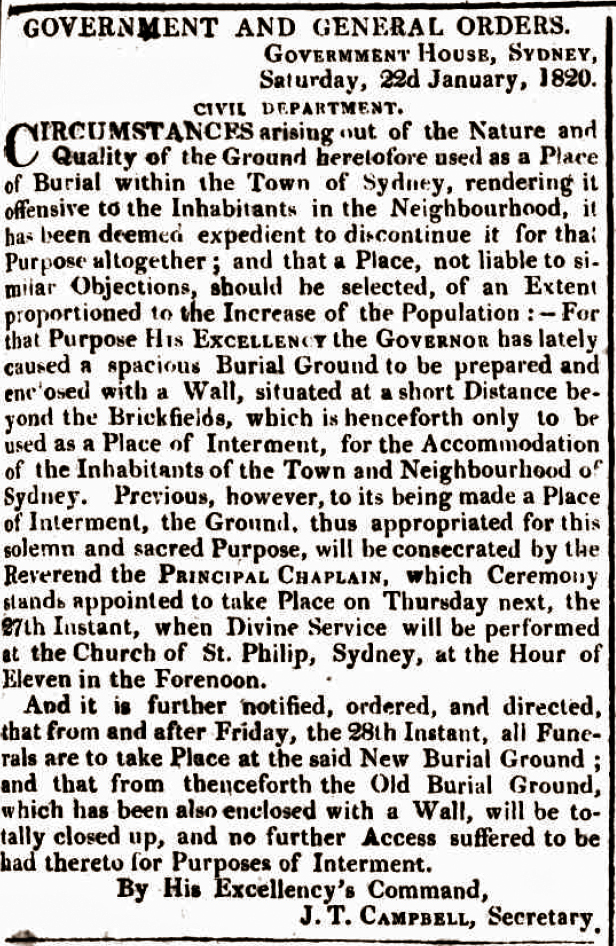

[media]The burial grounds were located near sandhills on the southern outskirts of Sydney, at Devonshire and Elizabeth Streets, at what is now Central Railway Station. Originally 4 acres (1.6 hectares) of land was set aside for a Church of England burial ground to replace the Old Burial Ground in George Street. The cemetery was consecrated in January 1820, but the first burial had already taken place the previous year.[1]

Subsequently, other denominations were allotted adjacent land for burial grounds upon application to the colonial government. As the 1842 plan of southern Sydney shows, the layout of the Devonshire Street cemeteries was an ad hoc arrangement, responding to the needs of the different religious communities for burial space.[2] The Roman Catholics and Presbyterians were given land in 1825. Over the next 14 years land was also granted to the Jewish community, Wesleyans, Quakers and Congregationalists.

[media]By 1836, there were in fact seven burial grounds on the site, covering a total of approximately 12 acres (4.9 hectares). Devonshire Street was not a general cemetery as we know the concept today, but seven distinct church cemeteries. You could not walk from area to area.

Each religious group managed its own burial ground, which was fenced, had an exclusive entrance and its own scale of fees and charges. Charges for a grave with permission for a headstone varied from seven shillings and sixpence in the Presbyterian and Wesleyan burial grounds, to 12 shillings in the Roman Catholic ground and 15 shillings in the Congregational ground.[3]

Layout and location

[media]The layout and location of Devonshire Street Cemetery placed Sydney at the forefront of cemetery design. It was the colonials’ first clear response to the garden cemetery movement in Britain. It was located on the outskirts of a populous town, on an elevated site, with picturesque views of the city and the harbour.

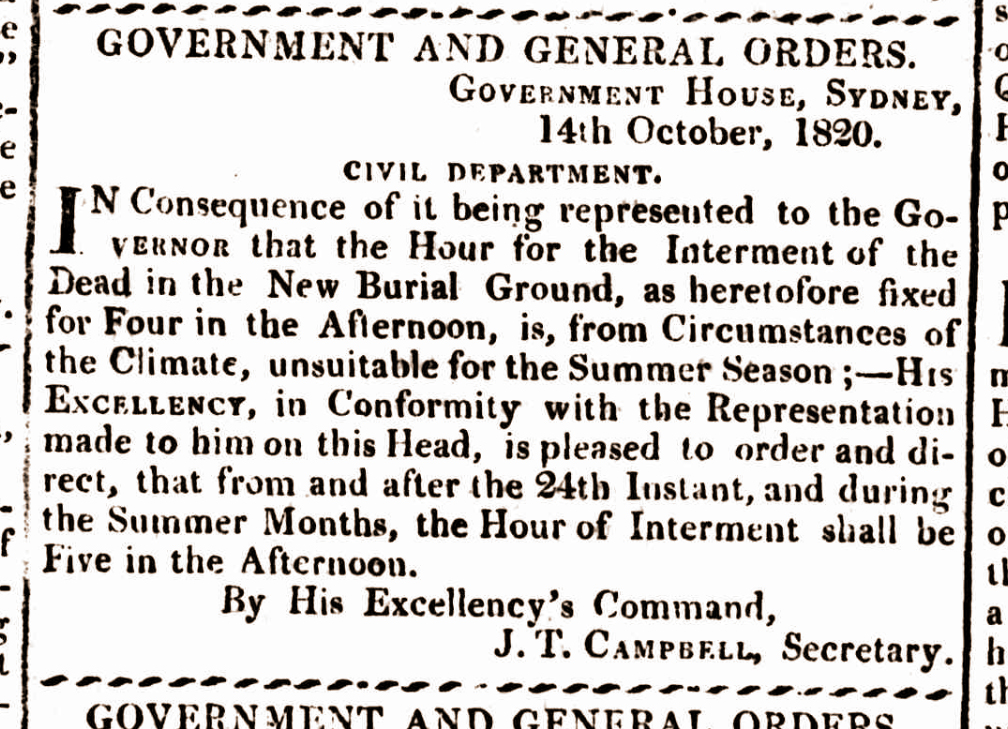

Regulations for the Church of England burial ground were published in the Sydney Gazette in 1820. The orientation of graves were to be east-west in a line following the British tradition, with the economical use of ground. The direction that vaults should be placed together in one area suggests the burial ground was divided into at least two sections: an area for graves and an area for vaults. In addition, one corner of the cemetery was ‘set apart by the Assistant Chaplain for peculiar and special Purposes, at the Discretion of the said Chaplain’.[4] While not made explicit in the regulations, this area was probably used for the unbaptised, executed criminals, and suicides. These directions for laying out cemeteries were soon circulated to all chaplains regulating Church of England cemeteries in New South Wales.

Prominent burials

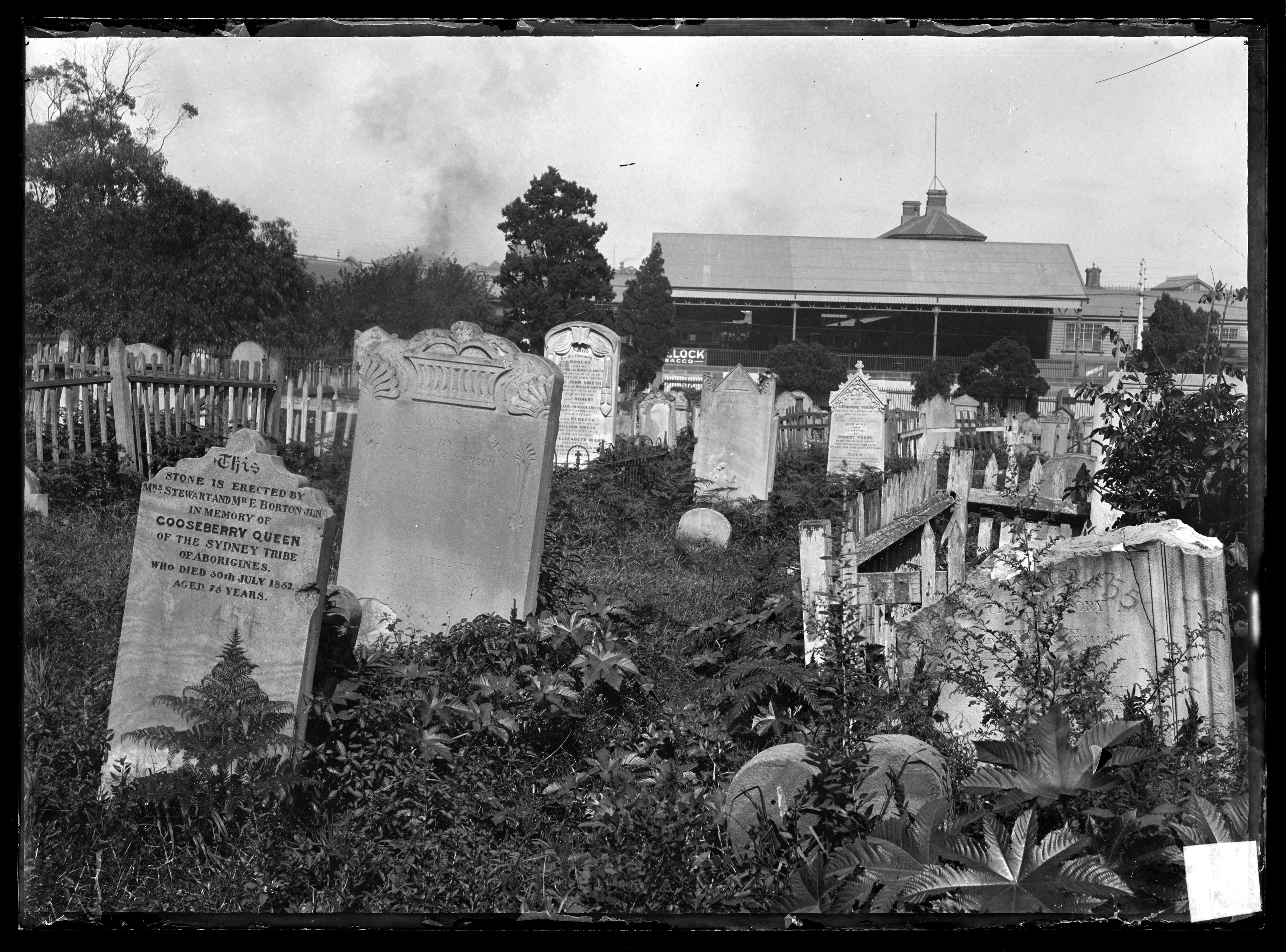

[media]Devonshire Street Cemetery was the principal burial ground for Sydney between 1820 and 1866, and many prominent historical figures were buried there. There were First Fleeters, such as the brewer James Squire , who died in 1822. There were colonial firsts – such as Isaac Nichols, the first postmaster (died 1819) and George Howe, the first Government Printer (died 1821). Allan Cunningham, botanist and explorer, who died in 1839, was originally buried there (his remains were later reinterred in the Royal Botanic Gardens), as were merchants and businessmen such as Samuel Terry (d.1838) and Simeon Lord (d.1840). Cora Goosebery, wife of Bungaree, was buried here by white friends in 1852.

Overcrowding

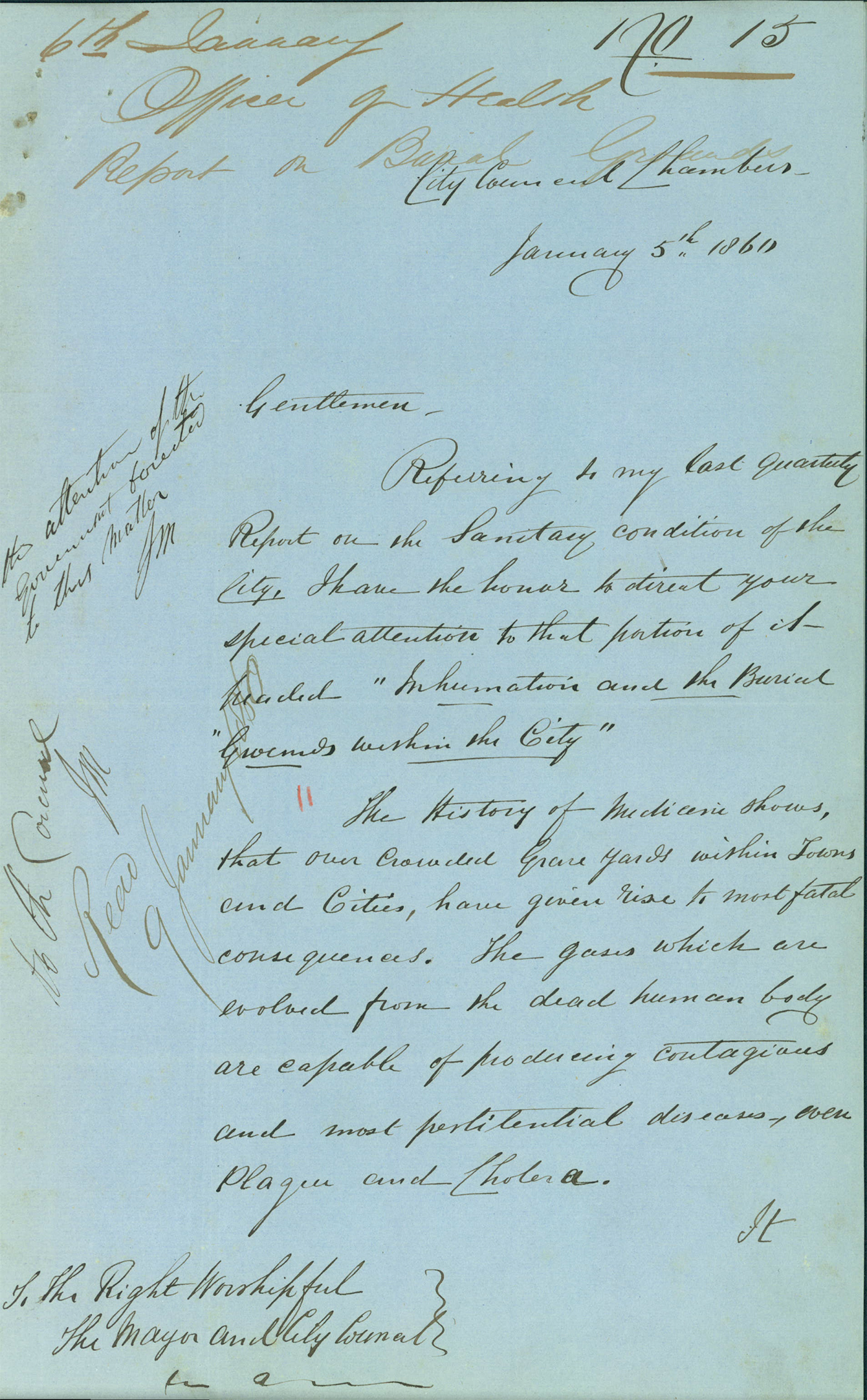

By the 1840s these burial grounds were already becoming crowded. In 1843 the Bishop of Sydney complained:

the burial ground … belonging to the Church of England, is so completely occupied that not only are decency and propriety much outraged by its crowded state, but it is actually impossible to find room for more bodies.[5]

[media]Five years later, the Church of England was still trying to force more bodies in. Finally the church gave up on the government and set up the Church of England Cemetery Company, which established the Camperdown Cemetery in 1849.

Problems were not confined to the Church of England portion of the Devonshire Street cemetery. Henry Graham, the City Health Officer, described to a parliamentary inquiry the poor depth of burials in all the grounds. He claimed to have seen bodies in the Sydney cemeteries ‘so near the surface that you could just touch them with a walking-stick or umbrella’.[6]

The cemeteries were formally closed to new burials in 1867, following the opening of The Necropolis at Haslem's Creek. Burials in family vaults and graves could continue upon application to the Colonial Secretary.

Resumption and recording

[media]By 1878 the burial grounds were thoroughly neglected and, as the cemetery was now in the centre of a busy city, there were calls for its complete closure and removal. A proposal to resume the cemetery for railway purposes was seriously considered by the parliament in 1882.[7] But it was not until 1901 that the NSW government finally resumed the Devonshire Street Cemetery to make way for Central Railway Station. Relatives and descendants were invited to claim headstones and remains, and remove them to other cemeteries at government expense.[8]

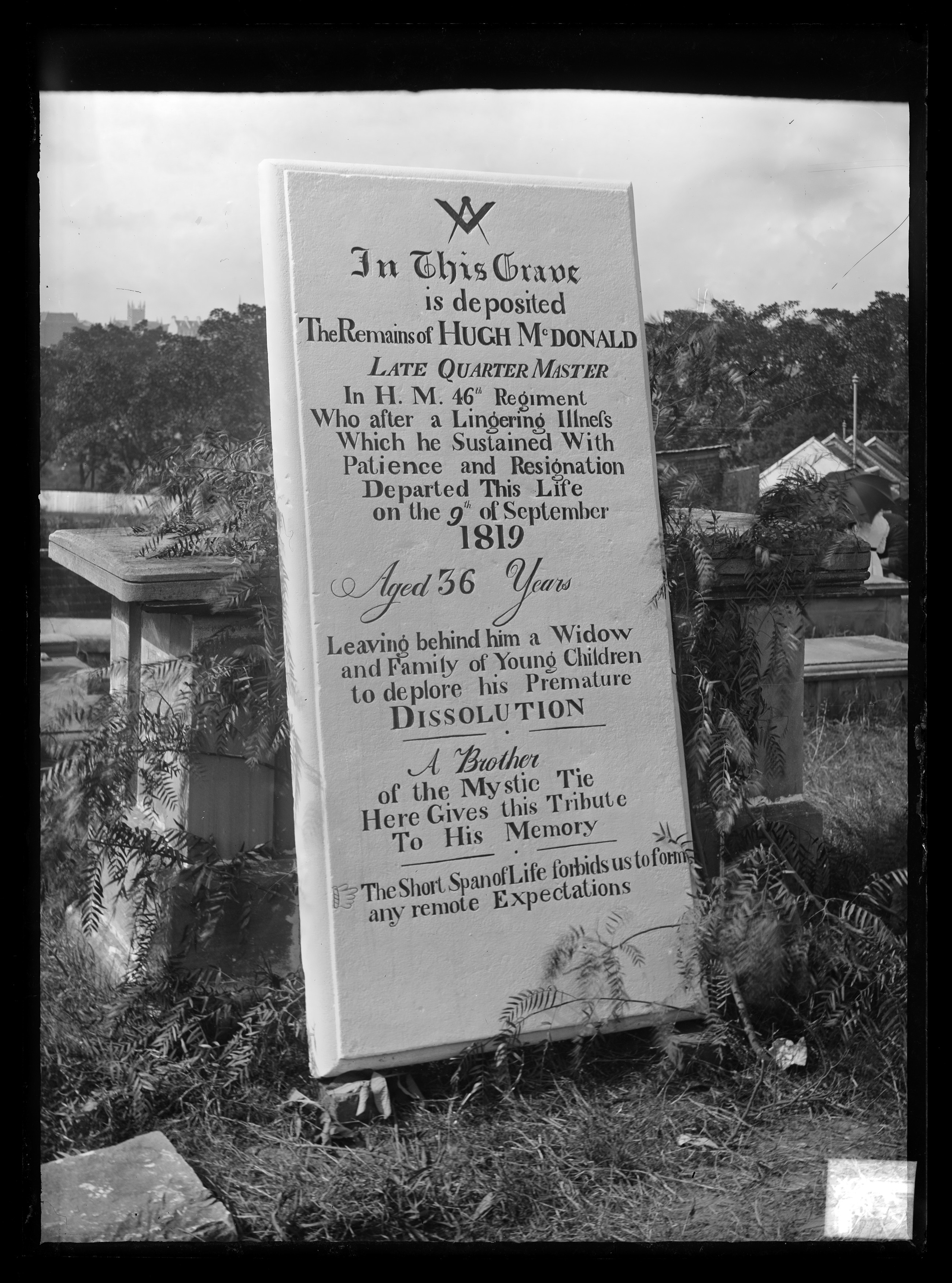

[media]Concerned at the loss of these early colonial headstones, ardent amateur historians and members of the newly formed Australian Historical Society, Arthur George Foster and his wife Ethel transcribed and photographed many of the headstones on the eve of their dispersal. They gave their attention mainly to the Church of England Burial Ground, but a clutch of inscriptions were also recorded from the Roman Catholic, Jewish, Presbyterian, Congregational and Wesleyan burial grounds. Mrs Foster’s photography captures the simplicity of the Neoclassical memorials and elements of the cemetery’s layout, while her husband’s detailed transcriptions of the decorative and spatial elements of the lettering, which include headstone decorative elements and even the names of monumental masons, are the earliest comprehensive collection sepulchral monuments in New South Wales.[9]

Reinterment

[media]The total number of burials may never be known with certainty. Approximately 8,500 remains were claimed by descendants and removed, with the associated monumentation, to other cemeteries.

Those left unclaimed – somewhere around 30,000 – were removed to La Perouse, along with about 2800 memorials. A special tramway was laid down to transport the remains to their new home at the Bunnerong Cemetery.

Many of the new burial sites have not survived but in 1973 the remaining monuments were consolidated and moved again to create the Pioneer Memorial Park.

References

AG Foster, 'The Sandhills. An Historic Cemetery', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol 5 part 4, 1919, pp.152-195

Keith A Johnson & Malcolm R Sainty, Sydney Burial Ground 1819–1901: Elizabeth and Devonshire Streets and History of Sydney's Early Cemeteries from 1788, Library of Australian History, Sydney, 2001

Lisa Murray, Sydney Cemeteries: a field guide, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, 2016

Sue Zelinka, Tender sympathies : a social history of Botany Cemetery and the Eastern Suburbs Crematorium, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1991

Notes

[1]‘Government and General Orders’, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 29 January 1820, p1, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2179242 viewed 22 March 2019; Hugh McDeonald, Quartermaster of the 46th Regiment was buried in the new cemetery on 9 September 1819, 'at the instance of the deceased, who had repeatedly, during his illness, expressed a desire to that effect', Family Notices, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 11 September 1819, p3, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2178948 viewed 2 September 2019

[2] Plan of 'Redfern's Grant' forming the Southern Extension of the Town of Sydney subdivided into allotments for sale by Mr Stubbs on 16 March 1842. Edward J. H. Knapp, surveyor, R. Clint, lithographer, Sydney 1842, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales (M Z/M3 811.18193/1842/1) https://search.sl.nsw.gov.au/permalink/f/lg5tom/SLNSW_ALMA21134828060002626

[3] Select Committee - Management of Burial Grounds’, NSW Legislative Council Votes & Proceedings, 1855, part 3: Mr J Curtis Q. 64, p1

[4] ‘Government and General Orders’, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 29 January 1820, p1, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2179242 viewed 22 March 2019

[5] ‘Burial Grounds, Sydney (and proposed general cemetery)’, NSW Legislative Assembly Votes & Proceedings, 1863-64, Vol 5 : Lord Bishop of Sydney to Colonial Secretary, 13 September 1843. Part II, Letter no. 1, p35

[6] ‘Progress Report from the Select Committee on the Camperdown and Randwick Cemeteries Bill’, NSW Legislative Council Votes & Proceedings, Vol 2, 1866, p634, Q154

[7] 'Parliament', The Sydney Daily Telegraph, 21 October 1882, p6, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article238471565 viewed 2 September 2019

[8] 'City Railway Extension and Devonshire Street Cemetery', Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales, 15 March 1901, p2294, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article226381524 viewed 22 March 2019

[9] Foster Collection. Devonshire Street Cemetery Epitaph Books. ML MSS B765-767, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales; Photographs of tombstones in Devonshire Street Cemetery, with typescript indices, 1900-1901 / Josephine Ethel Foster (Mrs Arthur George), PXB 768; Series 02, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales: Glass negatives of headstones in Devonshire Street Cemetery, Sydney, and other cemeteries, ca. 1900-1914 / Mrs. Arthur George Foster ON 146/nos. 330-485, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.