The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Celebrating the end of World War I

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Celebrating the end of World War I

[media]The long years of World War One, from 1914 to 1918, took a toll on the City of Sydney and its inhabitants. When peace was finally negotiated and the Armistice signed, the celebrations filled the city. More sombre Peace Day commemorations followed after the signing of the Treaty of Versailles formalised the end of hostilities.

Over by Christmas

Sir Harry Barron, Governor of Western Australia, said on 11 September 1914 that 'he would like to bet that the war would be over by Christmas'. [1] The German Kaiser Wilhelm II told his troops as they left for the front in August 1914 'You will be home before the leaves fall from the trees', meaning in the European autumn. [2] Had either the Governor or the Kaiser placed bets on this, they would have lost. As the Australian Worker cheekily observed, 'Some people say that the war will be over by Christmas. But they don't say which Christmas.' [3]

The war dragged on through four Christmases, with neither side making significant progress. It stopped just six weeks short of a fifth year, by which time 60,000 Australians had been killed and 160,000 wounded, some of them permanently disabled.

Peace at last

[media] Rumours of Germany's capitulation circulated around the world on Friday 8 November 1918. In Sydney and suburbs cheering crowds filled the streets and many businesses closed to allow staff to participate. However, in the absence of official speeches and announcements the crowds dispersed, though the revelry continued into the evening. It was described as an unprecedented display of spontaneous celebration, and foreshadowed even larger gatherings when the official news eventually came. [4]

[media]Finally, on the evening of Monday 11 November 1918 official news was received in Australia that the Armistice had been signed. Church bells rang, trains and ferries sounded their horns, and cheering crowds assembled in every neighbourhood. Despite the late hour, huge crowds poured into the city and choked all major streets for several hours. The Sydney Morning Herald said the next day that 'never in the history of Sydney did a greater flood of passengers flow over the evening service of trams, trains, and ferries.' By 9 pm the crowds in Martin Place, Pitt Street and George Street were so dense that movement was almost impossible. Extra trams were hurriedly put into service to bring people in from the suburbs but were immediately overcrowded. Services in the city centre had to be suspended because the great mass of people made it impossible for the police to keep the tramlines clear. [5]

A public holiday

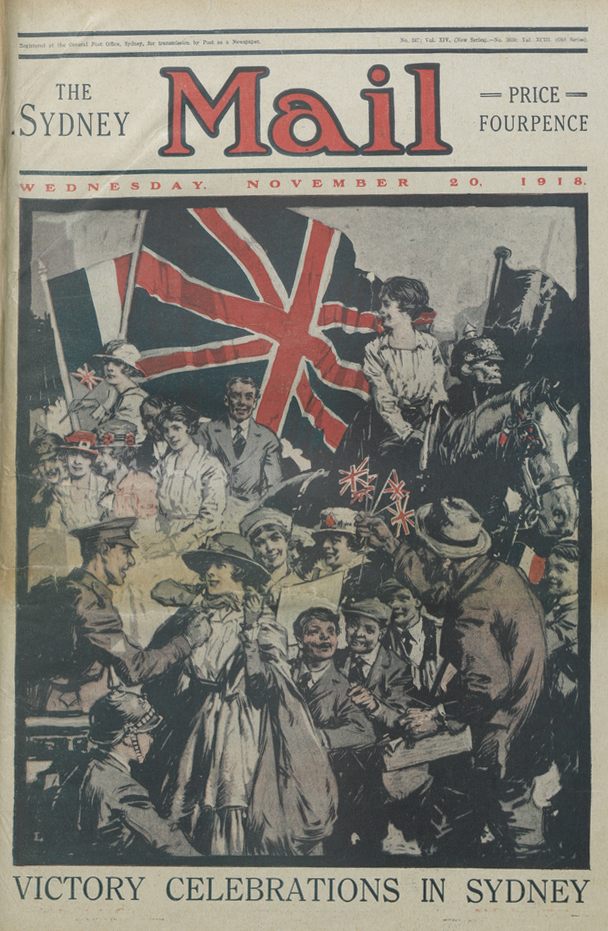

Tuesday 12 November was declared a public holiday. The bell in the General Post Office tower rang for ten minutes from 9 am and for five minutes every half hour thereafter until noon. Church bells also rang out. Enormous crowds filled the city, waving flags, throwing confetti. Brass bands played and everyone seemed to have a whistle or a rattle – the noise was deafening. The Kaiser was ceremonially hanged and then burned from the AMP Building and the Sydney Mail Building.

[media]The Governor, the Premier and the Lord Mayor spoke at noon to densely packed and cheering crowds in Martin Place. The national anthem – ‘God Save the King’ – and 'Rule Britannia' were sung. In the evening many buildings were illuminated, several with huge signs proclaiming 'Peace' or 'Victory', and special evening performances at the various theatres concluded a day of unprecedented celebration and excitement. Even the prisoners in the Long Bay State Penitentiary were included in the celebrations, assembling in the chapel and singing patriotic songs. The Attorney-General addressed them and announced that, to celebrate the victory, an extra period would be remitted from the sentences of all who earned good conduct marks. [6]

In the suburbs, processions, patriotic meetings and celebratory functions in town halls, schools of arts, local parks or at major intersections marked the peace and honoured local members of the AIF. There were parades of schoolchildren and returned soldiers, and many churches held thanksgiving services. More effigies of the Kaiser were burned in several suburbs as well as in the city. Perhaps the only people unable to join in the celebrations were final year high school students sitting for the Leaving Certificate. The Department of Public Instruction insisted that the examinations were to proceed, regardless of the public holidays. [7]

Wednesday 13 November was another day of celebration, but of a more official kind, though no less exuberant. Church services gave thanks for victory and prayers for all those who had been killed. An estimated 200,000 people gathered in the Domain at 3 pm for a public celebration, preceded by a march through the city of 6,000 returned soldiers and sailors, followed by the mothers and wives of many still serving or who had been killed. Bands, hymns, patriotic songs and speeches were the order of the day and at the conclusion of the function many tens of thousands of excited people poured back into the city and thronged Martin Place and other major streets. One peculiarly fitting celebratory function in the evening was held by the Highland Society of New South Wales in its refurbished headquarters which had formerly been the Sydney German Club. [8]

The Sydney Evening News remarked that 'Those who took part in the great rejoicings in Sydney in connection with the signing of the armistice will remember the celebrations to the end of their lives …' [9] The Sydney Mirror offered a prize for the best essay by a child under 12 on the topic 'What I Did When the Armistice was Signed'. [10]

Peace Day

The Treaty of Versailles, signed on 28 June 1919, formally ended hostilities. To mark this final ending of 'the war to end all wars' major buildings were decorated with flags. On 30 June church services were held and Australian and British ships fired a 101-gun salute in Sydney Harbour. Official celebrations were held on Saturday 19 July, which was declared 'Peace Day' throughout the British Empire. On the Friday many schools held ceremonies, often including recognition of teachers or former pupils who had served or died. In some suburbs, such as Annandale, Petersham and Redfern, a number of schools combined for joint ceremonies of commemoration including marches and sports carnivals. All schoolchildren were given a peace medal to commemorate the end of the war. [11]

On Peace Day in Sydney major buildings were decorated, bells were rung in churches and public buildings, and huge crowds flocked to the city. Unlike the delirious rejoicing of November 1918, this was a sober celebration and recognition of the huge sacrifice of death and disability among those who served. Indeed, some objected to any celebrations and urged that the money be spent instead to benefit the children of fallen soldiers. The government eventually agreed to scale back its initially ambitious plans. [12]

The major event was a march through the city by more than 10,000 sailors and soldiers, Red Cross and other war workers, a parade which stretched for more than three miles. 'There can never be another sight like it' proclaimed the Sydney Morning Herald. At 11.30 am the parade halted, the bands and choirs played and sang Kipling's 'Recessional', joined by many spectators, bugles sounded the 'Last Post' and three minutes of silence were observed across the city in commemoration of the fallen. A 21-gun salute was fired from the Domain at noon. The afternoon was given over to a regatta on the Harbour and a variety of sporting events. At night, buildings and ships in the harbour were illuminated, there was a fireworks display, and a chain of bonfires was lit around the Harbour and in many suburbs. Although it had been hoped that similar activities could be held in the various suburbs, Sydney was the focus for the day's activities, a fact which caused some complaint. [13]

Many special religious services were held on the Sunday, either in individual churches or as combined services in local parks or halls, often in conjunction with parades of children and returned servicemen. [14] As had occurred in 1918 when the peace treaty was signed, prisoners were granted remissions of a portion of their sentences, including five military offenders who had been convicted of desertion.

The war to end all wars was finally over.

Notes

[1] West Australian, 12 September 1914, 9

[2] David Walder, The Chanak Affair (London: Hutchinson, 1969), 21

[3] Australian Worker, 26 November 1914, 12

[4] Sydney Morning Herald, 9 November 1918, 13–14

[5] Sydney Morning Herald, 12 November 1918, 6

[6] Sydney Morning Herald, 13 November 1918, 10–11

[7] Blue Mountain Echo, 15 November 1918, 1

[8] Sydney Morning Herald, 14 November 1918, 7–8

[9] Evening News, 21 November 1918, 8

[10] Mirror, 22 November 1918, 9

[11] Sydney Morning Herald, 19 July 1919, pp 11–12

[12] Sunday Times, 9 February 1919, 3; 16 February 1919, 5; 23 February 1919, 3; 6 April 1919, 5; 13 April 1919, 3; 11 May 1919, 1

[13] Sunday Times, 27 July 1919, 4

[14] Sunday Times, 20 July 1919, 1–3; Sydney Morning Herald, 21 July 1919, 9–11

.