The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Cazneaux, Harold

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Cazneaux, Harold

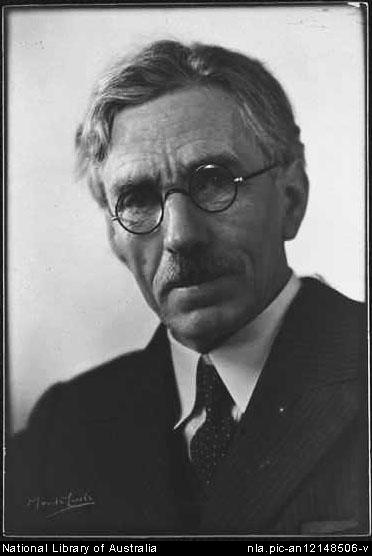

[media]Harold Cazneaux's life tells many stories. He lived a simple quiet life, enriched nonetheless by a stimulating environment of art, music and photography. His father Pierce Mott Cazneau [sic], and mother, Emma Florence Bentley, were photographers and accomplished musicians. They owned the photographic studio Cazneau and Connolly in Wellington, New Zealand, where Cazneaux was born on 30 March 1878. He spent his boyhood in Adelaide and at one time took art classes under HP Gill, who also taught Hans Heysen.

Early career

In 1904 he moved to Sydney and worked as an artist-retoucher at Freeman & Co in George Street. A year later he married his sweetheart and co-worker in Adelaide, Winifred Hodge. Their first home was a terrace house in Riley Street, North Sydney.

Cazneaux's first camera was a quarter-plate box camera which he affectionately nicknamed 'The Midge'. Although stout and heavy, 'The Midge' was portable and it became his constant companion. His favourite hunting grounds were Circular Quay, Surry Hills, Darlinghurst, Woolloomooloo, Balmain, Pyrmont and Millers Point. According to Cazneaux, the city streets, the waterfront, and the picturesque gardens and parks of the north shore 'hummed with pictures'. From May 1915, he lived with his wife, his five daughters, Rainbow, Jean, Beryl, Carmen and Joan and his son Harold at Ambleside in Dudley Street, Roseville.

In 1918, ill with overwork and dissatisfied with his job, Cazneaux resigned from Freeman & Co. He felt Freemans had undermined his opportunities to take on freelance work. Out of work and depressed, he suffered a nervous breakdown and was bedridden for 12 months. Eventually he moved his studio to his home, and worked there until his death.

Success

Between the wars, commissions ranging from commercial, industrial and domestic architecture to portraits and social functions kept Cazneaux extremely busy. In 1920 he employed Ethel Sly to cope with the overload. A co-worker with Cazneaux at Freeman's, Ethel was dark-eyed, attractive and competent, and she did the retouching, potting and finishing of photographs at Ambleside. She not only became his official factotum and invaluable assistant but also his devoted friend. Their association lasted for 14 years.

By 1928, for the first time in his career, Cazneaux could describe his financial situation as 'Capital OK' instead of 'Capital Nil' in a letter to a friend. He was able to settle debts, pay off his mortgage and buy the latest six-cylinder Silver Anniversary model Buick.

Photographing Sydney

[media]Sydney captivated Cazneaux from the time he first arrived in 1904. That fascination, early on in his career produced exceptional photographs, whose quality and diversity of subject matter received much admiration. A number of factors contributed to this astonishing achievement. The artistic trend of Pictorialism, which Cazneaux embraced wholeheartedly when it was introduced to Australia in the 1890s, was gaining popularity. The portability of the 'new' hand cameras sent keen photographers out into the great outdoors, and Cazneaux's impecuniousness bound him to Sydney and sent him exploring its crooked streets and alley ways on foot. The stifling atmosphere of his job in a city portrait studio meant he escaped to freedom beyond the confines of studio walls at every opportunity. Although he lamented the changing face of Sydney, with the coming of the machine age, the 'passing show outdoors' did not escape his camera or his written thoughts. In 1948 he noted,

The old Sydney is changing. The March of Time with modern ideas and progress is surely brushing aside much of the old — the picturesque and romantic character of Sydney's highways, byways and old buildings. Some still remain, hemmed in and shadowed by towering modern structures. Many of the old city habits and customs have vanished in the passing of the old city characters. Gone now are the famous Sydney hansom cabs, and the old-time cry of the friendly cabby; 'Cab, Sir Cab, Sir, right away, Sir.' Gone, too, are the lamplighters who went their rounds at dusk, leaving behind, as each lamp was lighted, the flickering and ghostly glare of gaslight.[1]

[media]Cazneaux's investigations of the alleyways and obscure lanes at The Rocks and Surry Hills were sometimes tinged with trepidation;

I recall my feelings of relief when I had retraced my steps. It may have been instinct, but suspicious and furtive glances were not lost on me. I felt something of the uncanny and of the underworld in the atmosphere. [2]

Nevertheless, the photographic enthusiast was not to be daunted by the intimidating character of such places. As he recalled,

Photography is difficult in this neighbourhood. To be successful the worker should have had some experience, as any nervousness of manner and lack of tact whilst working here would only end up by being ridiculed. However, go by all means and get broken in. Tact and expert manipulation of one's camera is necessary if we wish to deal successfully with side street work in this locality. Still, the chances are that you may not like to return again. [3]

Sydney in all weathers

Cazneaux considered that the romantic, liquid glow of a hesitant sun during the wet, misty mornings of winter made it an extraordinary season for taking photographs.

There is nothing more evocative than a wet winter's day in the city: the fruit and flower stalls of Sydney; William Street at dusk looking towards the city from Kings Cross; Macleay Street, Darlinghurst with its bohemian flavour. The sun high up in the air in the summer drags all the romance from the things I have talked about. But when the sun hangs low in the north in winter, then these things come to pass. [4]

[media]In the early morning, according to Cazneaux, 'one can simply revel in pictorial work, especially if there is a slight mist about'. He found the ferries emerging from and disappearing into the mist at Circular Quay very atmospheric and he took countless photographs standing on pontoons and landing stages with the camera 'held tight' against the railing. He spent hours watching pedestrians, bootlace-peddlers and spectacle-merchants, cabbies and flower-sellers along Martin Place. In the rain, he kept dry by buttoning his overcoat over the handle of the umbrella snuggled firmly over his chest, to keep both his hands free to manipulate the camera.

With the flower-sellers I prefer to work during the time afforded between showers, as their umbrellas, used as shades for the blooms, seem more in keeping with the elements, also the reflections are a help in their own way. [5]

To Cazneaux, the Archibald fountain at Hyde Park was tremendously alive, especially at nightfall. Even late at night when the city was deserted, Cazneaux could still 'hear its song'.

In summer it stands forth in all its bronze beauty but in winter it is clothed instead by romance. It might be stone for all we may know when the softness of the mist enshrouds it. At nightfall, around about that time when the lights of the city merge out clearly from the fading daylight, the fountain and the whole city becomes a piece of enchantment – a wonderful nocturne… [6]

Cazneaux found the subtle attraction of the huge city buildings irresistible, especially when they were enfolded by mist or washed by rain, their forms reflected in the pools of water beneath, with pedestrians hurrying to and fro causing 'fantastic reflections of themselves to dance along their feet'.

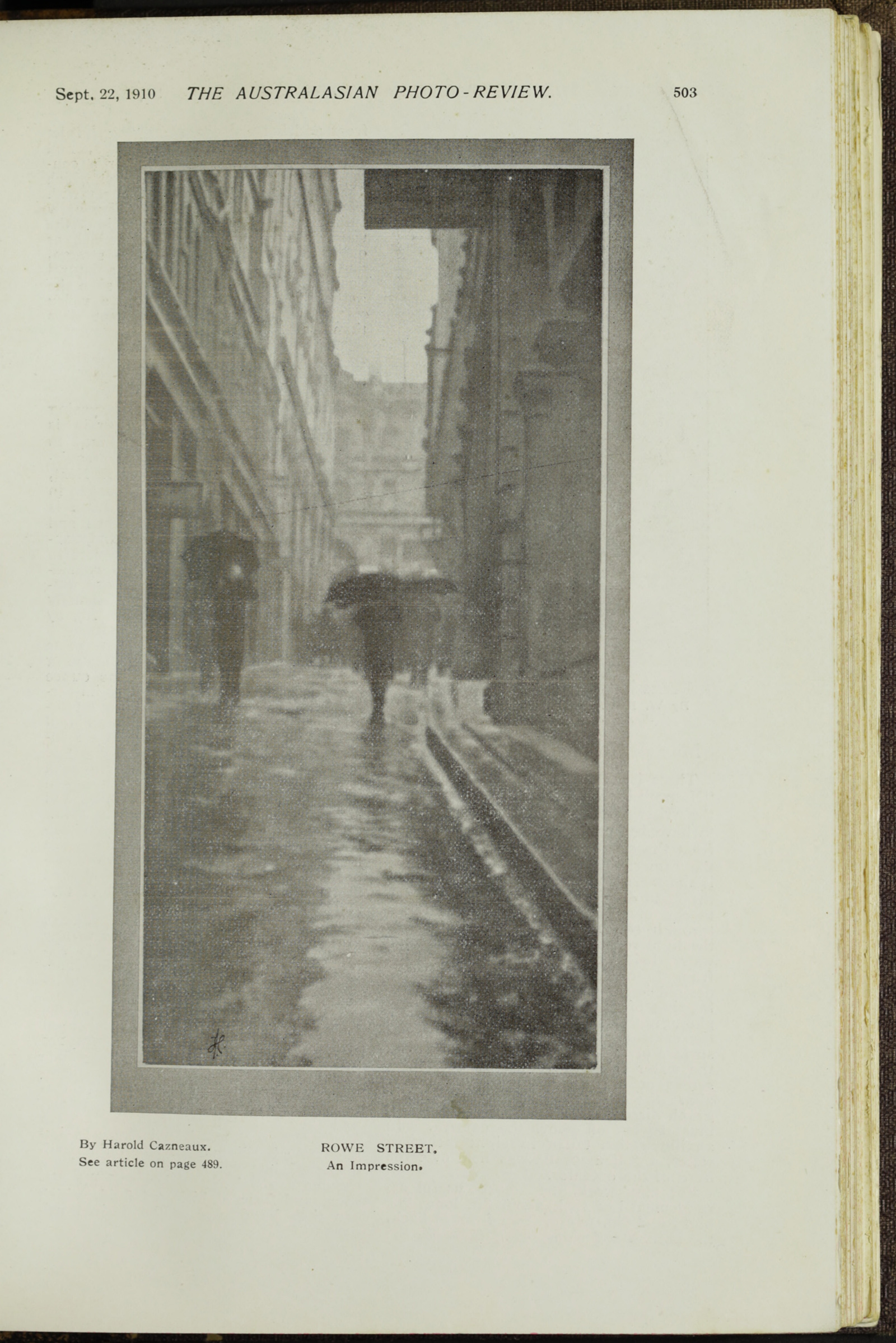

[media]Indeed, he gloried in rainy, dismal weather that would deter even the most foolhardy from venturing outdoors. Rowe Street , An Impression was taken during one such very wet and windy lunch break. As he noted,

…if anyone stands at the entrance of Rowe Street on a windy day they will get an idea of what a battle it was to hold a camera and an umbrella and be nearly jostled off the footpath by the hurry of the crowd, and at the same time watch the effect in the lane so as to get a suitable moment. I tell you it takes the wind out of one's sails, however, with patience and luck I got a chance to push the camera in between a few hurrying people and snapped the impression as I saw it. I think it would have been a funnier impression had anyone snapped me at the entrance battling with the elements. [7]

The versatility of the Australian sun also besotted Cazneaux. In his photographs, he experimented fearlessly with the resplendence of full sunlight, as well as the filigreed patterns made by filtered sunlight. He confronted and challenged light sources, shadows and reflections and cajoled the mysterious patterns they created into his photographs.

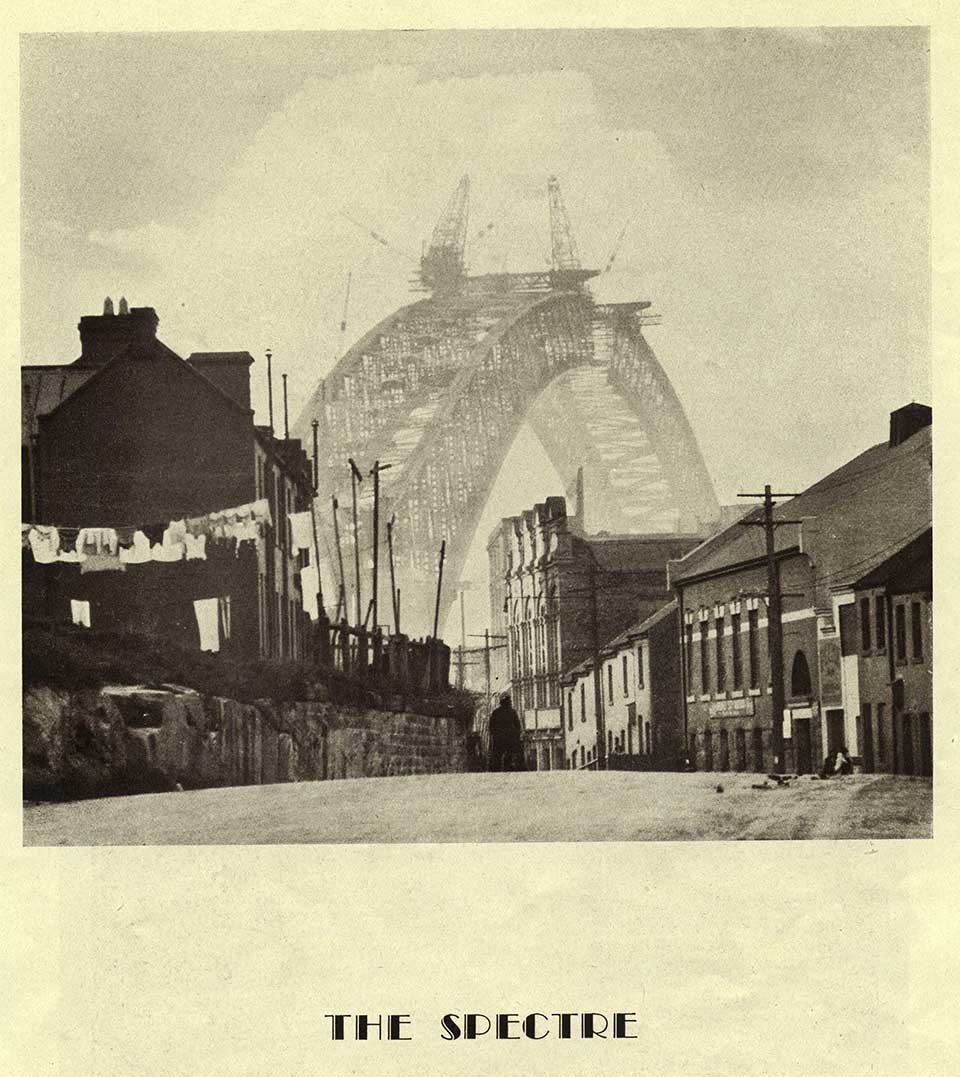

Portraits of the Bridge

The Sydney Harbour Bridge was a story in itself and many photographs were taken during the different stages of its construction. From the demolition of buildings and laying of foundations, to the opening ceremony and the famous 'cutting of the ribbon' incident by de Groot, Cazneaux captured it all. Looking through his camera lens, the Sydney skyline seemed to change overnight with the completion of the Harbour Bridge, an event that provoked nostalgia in him. As he wrote,

Something of the old spirit and character departed as the great highway surged forward, levelling old buildings, blotting out old streets and alleyways. All were dispersed in a cloud of historic rubble and dust. The great bridge rose up to the sky, and the march of modern improvements extended to the waterfront. Old lanes leading to old wharves; even the old ships and barges have now departed. It had always been an interesting locality, and there were possibilities always waiting for the camera man. The great change-over to modern machine traffic has almost driven the horse from the streets of Sydney. Electric trams, motor bus, car and taxi have brought speed, convenience and some physical comfort to all. But in the midst of all the hectic bustle, speed, noise and tension of this congested traffic, the vision may come to those who knew the Sydney of yesterday with its picturesque character and easy-going ways. [8]

[media]Nevertheless, the Sydney Harbour Bridge became the source of some of Cazneaux's finest work. His city photographs publicised his talent immensely. Although he felt that the Bridge had swept away some 'fine hunting grounds, possibilities were still about' and the Bridge itself provided what the ferries did for him in the past, a perfect vantage point for his photographic shots.

Artist photographer

Although Cazneaux did not welcome drastic modernisation of the city landscape, he conceded that change was inevitable;

The old timer must fit in with the march of progress, a new outlook must be adopted with the passing of the old … Whatever pictures are made of our great Sydney today will in future years have some historical interest and value. As time marches on there will always be a 'Sydney of Yesterday'. [9]

Harold Cazneaux ranks as one of Australia's great photographic artists. Max Dupain, that other eminent Australian photographer, acknowledged Cazneaux's place as the father of modern Australian photography. His greatest achievement is the result of his fascination with Sydney which produced exceptional photographs that captured the essence of an evolving metropolis.

Cazneaux also knew his own worth. He was an indefatigable teacher, exhibitor, critic, writer and judge, but most importantly, he was a fine photographer and artist. He was purely self-taught and did not specialise in any particular subject. Between 1906 and 1952, his articles and photographs were featured regularly in Australian and overseas periodicals, books and journals. In particular, his photographs in The Home magazine continue to interest historians and the general public with insights into the lives of Australians during the 1920s and 1930s. He won 32 awards, most of them international. Harold Cazneaux died in his sleep, on 19 June 1953, aged 75.

References

Zeny Edwards, Sunlight and Shadow: The Lifework of Harold Cazneaux, Wild and Woolley, Sydney, 1996

Notes

[1] Harold Cazneaux, 'The Sydney of Yesterday', Contemporary Photography, May-June 1948, p 23

[2] Harold Cazneaux, 'The Sydney of Yesterday', Contemporary Photography, May-June 1948, p 23

[3] Harold Cazneaux, 'In and about the city with a hand-camera', The Australasian Photo-Review, 22 September 1910, p 492

[4] Harold Cazneaux, 'Winter Time Photography', handwritten notes, 27 June 1933

[5] Harold Cazneaux, 'In and about the city with a hand-camera', The Australasian Photo-Review, 22 September 1910, p 490

[6] Harold Cazneaux, 'In and about the city with a hand-camera', The Australasian Photo-Review, 22 September 1910, p 490

[7] Harold Cazneaux, 'Comments on the One Man Show', handwritten notes, 23 March 1909

[8] Harold Cazneaux, 'The Sydney of Yesterday', Contemporary Photography, May-June 1948, p 22

[9] Harold Cazneaux, 'The Sydney of Yesterday', Contemporary Photography, May-June 1948, pp 25, 32

.