The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Bungaree

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Bungaree

Bungaree [media]or Boongarie (c1775–1830), from Broken Bay, north of Sydney, adopted the role of a mediator between the English colonists and the Aboriginal people. He sailed in that capacity with Matthew Flinders, becoming the first Australian to circumnavigate the continent.

In mid-life he found a patron in Governor Lachlan Macquarie, who made Bungaree 'Chief of the Broken Bay Tribe', set aside land and gave him a boat for fishing. In his later life Bungaree, while still respected as an Aboriginal leader, was regarded as the best-known character in the streets of Sydney.

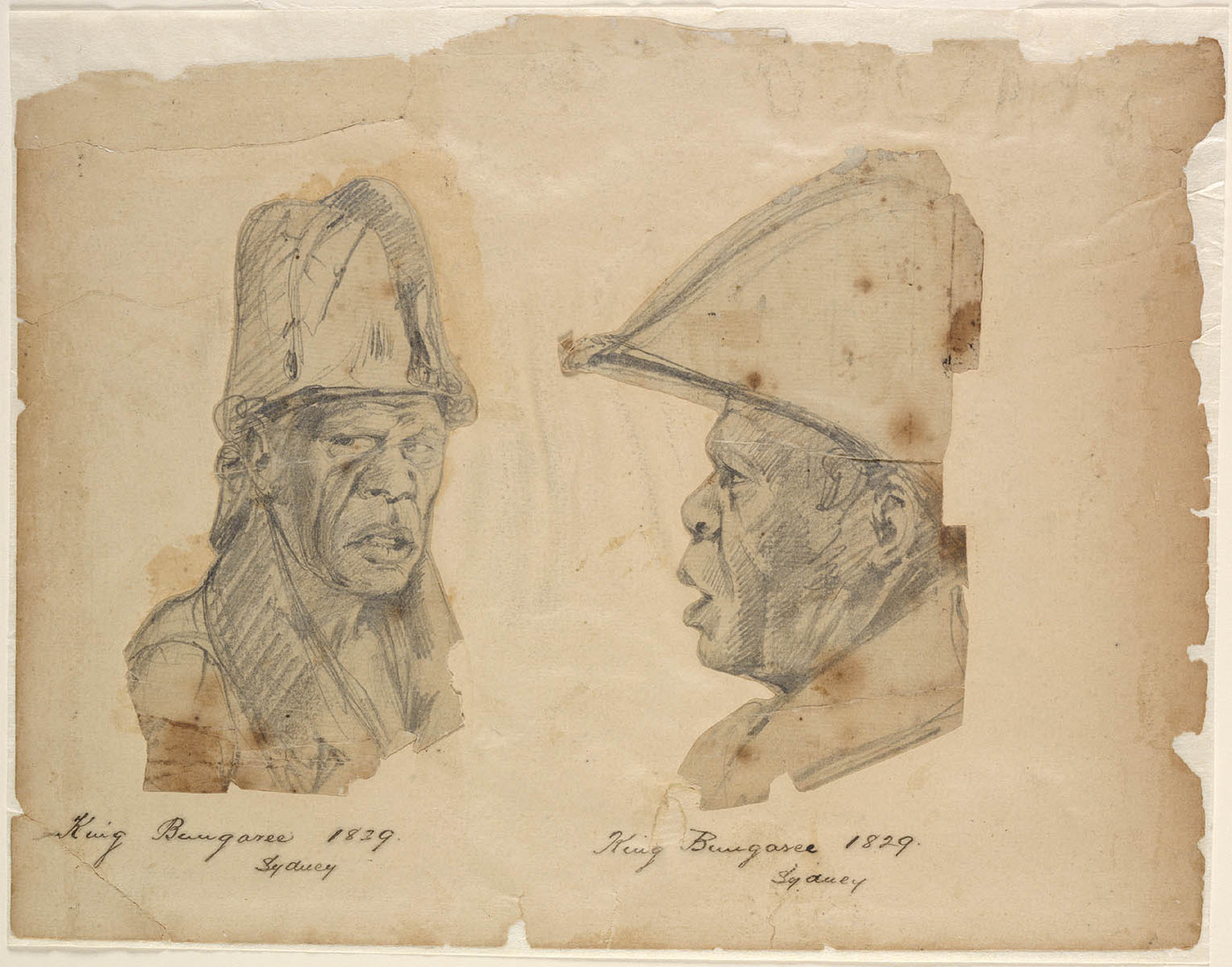

So many artists were drawn to Bungaree's distinctive image that today he appears in a rich gallery of 18 portraits and other illustrations. This was an extraordinary number as there were only two or three portraits of Governor Macquarie. The artists included Augustus Earle, Pavel Mikhailov, Jules Lejeune, Charles Rodius, Phillip Parker King, John Carmichael and William Henry Fernyhough.

[media]The most famous portrait is Earle's oil, 'Bungaree, A native of New South Wales', painted in 1826, in which Bungaree, wearing a scarlet jacket with brass buttons and gold lace, extends his black cocked hat in greeting. There is an air of genuine nobility in the expression and bearing of Bungaree, who stands on the heights of The Rocks, dominating Fort Macquarie and the ships of Royal Navy China Squadron off Bennelong Point in the background. [1]

On his chest hangs the crescent-shaped brass breastplate or gorget given to him by his patron Governor Macquarie, who twice established Bungaree and his people at Gurrugal, or Georges Head, near the present Sydney suburb of Mosman. It was inscribed 'Boongaree, Chief of the Broken Bay Tribe, 1815'.

As soon as any ship came through the Sydney Heads, Bungaree would arrive in his fishing boat, rowed by two of his wives. Dressed in an old military jacket, tattered trousers and his trademark hat, he climbed on board to welcome newcomers to 'his' country. Doffing his hat, bowing deeply and grinning widely, Bungaree would ask to drink the captain's health in rum or brandy. He then inspected the ship's pantry and levied his 'tribute', which he received in the form of 'presents' or 'loans'.

A clever mimic, Bungaree could imitate the walk, gestures and expressions of past governors of New South Wales. Like Shakespeare's clown in Twelfth Night, he was 'wise enough to play the fool' and used his humorous talents to obtain clothes, tea, tobacco, bread, sugar and rum for himself and his people. As author and historian Geoffrey Dutton commented: 'He mocked the white men by mocking himself'. [2]

Bungaree's picturesque appearance, good nature and shrewd intelligence set him apart from other Aboriginal people living on the fringes of the convict settlement at Sydney Cove. The Sydney Gazette described him in 1804 as 'a native distinguished by his remarkable courtesy'. [3]

He encountered the famous European explorers of his time like the Russian Captain Fabian von Bellingshausen and French navigators including Jules Dumont d'Urville, René-Primavère Lesson and Baron Hyacinth de Bougainville.

The negotiator

Long before the image of a flamboyant joker, mimic, beggar and drunkard stamped itself on the historical memory, the adventurous young Bungaree played a key role in Australia's early coastal exploration.

'Nanbarry, Wingal, Bongary, Port Jackson for a Passage to Norfolk Island, 29 May 1798'. This entry in the muster of HMS Reliance records the first known voyage of the famous Broken Bay seafarer. On this 60-day round trip the young English naval lieutenant Matthew Flinders met and came to respect Bungaree. [4]

In 1799 Flinders took Bungaree with him on a coastal survey voyage to Bribie Island and Hervey Bay on the 25-ton capacity decked longboat Norfolk. Flinders relied on Bungaree's knowledge of Aboriginal protocol and skill as a go-between with coastal Aborigines during this six-week voyage. Fifteen years later, in A Voyage to Terra Australis, Flinders wrote that Bungaree's 'good disposition and open and manly conduct had attracted my esteem.' [5]

Bungaree took part in the establishment of the first penal settlement at the Hunter River (Newcastle) in 1801. After landing from Lady Nelson, Surgeon John Harris told Governor Philip Gidley King that 'Bonjary ran off ... and has since not returned'. [6]

During 1802–03 Bungaree became the first Australian-born circumnavigator when he sailed with Flinders in the sloop HMS Investigator, which also visited Timor. On this long voyage Bungaree used his knowledge of Aboriginal protocol to negotiate peaceful meetings with local Indigenous people.

In May 1804 Bungaree escorted six Aboriginal men returning to the Hunter River from Sydney in the ship Resource. The commandant at Newcastle, Lieutenant Charles Menzies, valued Bungaree's help in capturing runaway convicts and called him 'the most Intelligent of that race I have as yet Seen'. [7] However, in October Menzies reported that convicts had taken revenge by killing Bungaree's father 'in the most brutal manner'. [8]

About this time Bungaree took his first wife Matora. According to the Reverend Lancelot Threlkeld, mut-tau-ra, meant 'small snapper' in the Newcastle-Lake Macquarie ('Awabagal') language group, to which she probably belonged. [9]

Bungaree and his Brisbane Water people settled on the north shore of Port Jackson, bringing their Garigal or Karegal language with them. [10]

On 31 January 1815, Governor Lachlan Macquarie reserved land and erected huts at Georges Head for Bungaree and his Brisbane Water people to 'Settle and Cultivate'. They were given a fishing boat, clothing, seeds and farming implements. The governor's wife Elizabeth Macquarie gave Bungaree a sow and pigs, a pair of Muscovy ducks and outfits for Matora and their daughter. Bungaree's statement 'These are my people … This is my shore', addressed to the Russian navigator Captain Bellingshausen in 1820, can be seen as a land claim over the north shore of Port Jackson. [11]

At the age of 42 Bungaree again went to sea with Governor King's son, Captain Phillip Parker King, who had orders to survey the north and west coasts of Australia. King, later Australia's first admiral, wrote:

He was about forty-five years of age, of a sharp, intelligent and unassuming disposition, and promised to be of much service to us in our intercourse with the natives.

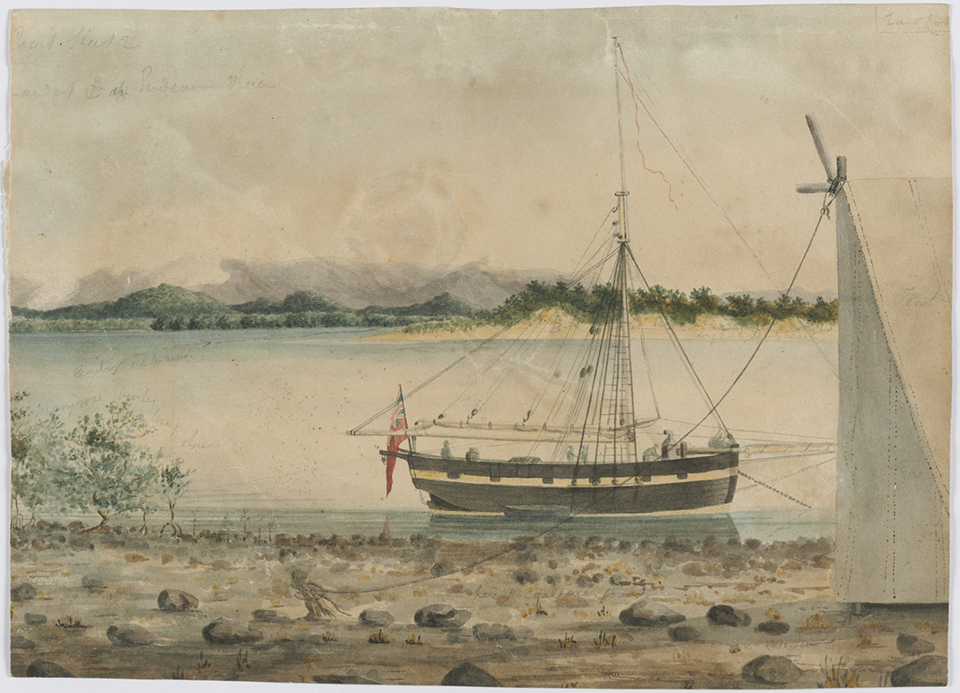

[media]The snub-nosed cutter Mermaid left Port Jackson on 22 December 1817, put into Twofold Bay, steered through Bass Strait, and followed the Great Australian Bight to King George Sound (Albany). [12] On this voyage Bungaree also assisted the botanist Alan Cunningham, who called Bungaree 'our worthy native chief' and praised 'the character of this enterprising Australian', a very early use of the name. [13]

Bungaree was a key figure in Governor Macquarie's 'Experiment towards the Civilization of these Natives', a plan outlined in a letter sent to Earl Bathurst in 1814. [14] Bungaree usually attended the annual Native Conference instituted by Macquarie, at which Aboriginal people gathered to feast on beef and liquor at Parramatta. His absence was noted in 1822 when Bungaree was seen 'reclining by his fire upon the grassy upland bordering on Bennelong's Point'. [15] On the day before his departure to England in February 1822, Macquarie went to the Georges Head farm to visit Bungaree for the last time and to introduce him to his successor, Sir Thomas Brisbane, who promised Bungaree a new fishing boat and nets. [16]

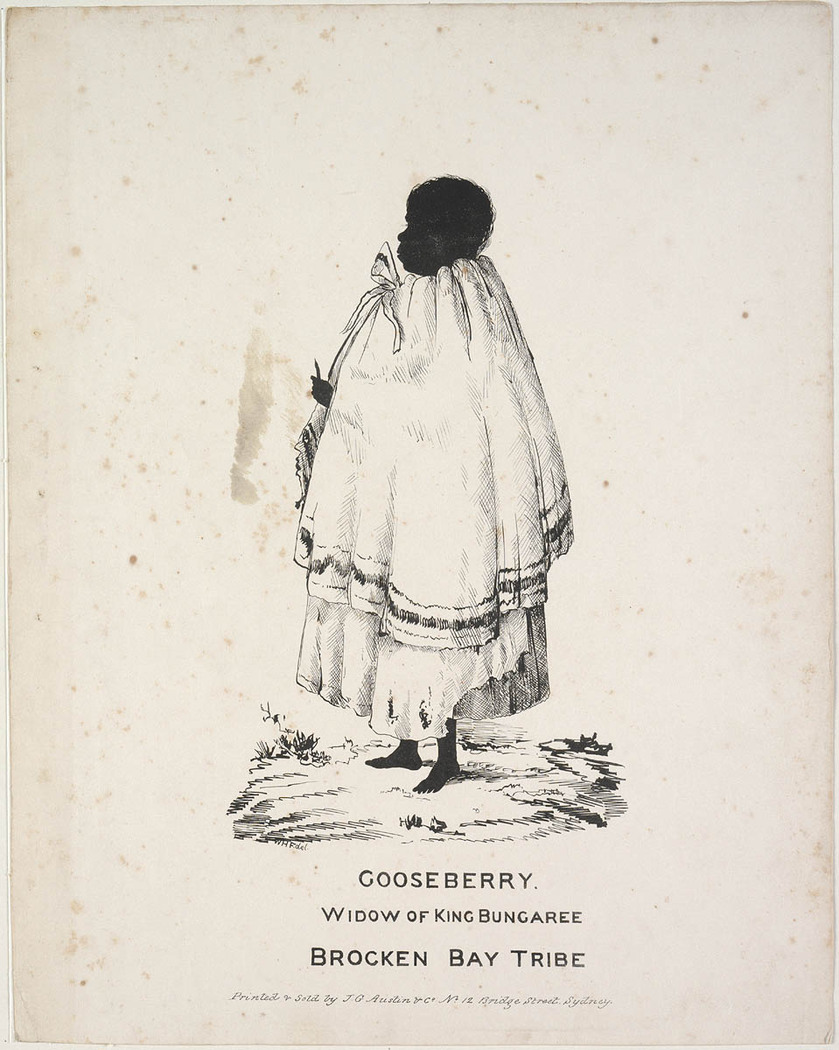

Bungaree's [media]widow Cora Gooseberry (c1777–1852) became a well-known identity in the Sydney streets. Born as Carra or Kaaroo, she was the daughter of Moorooboora, leader of the Murro-Ore (Pathway Place) clan, named from muru (pathway) and Boora (Long Bay). [17]

'Onion, Boatman, Broomstick, Askabout and Pincher' were spurious names invented by the fiction writer John Lang for Bungaree's reputed wives in 'Bungaree, King of the Blacks' published in Charles Dickens's weekly journal All the Year Round (London 1859). In the same article, Lang has Bungaree imitating two governors, Lieutenant General Ralph Darling and Sir George Gipps, who did not come to New South Wales until after Bungaree's death. [18]

Bungaree's eldest son, Bowen or Boin, and his younger brother Toby or Toúbi were born near the turn of the nineteenth century. Bungaree had a daughter and Boio, nicknamed Long Dick, born between 1814 and 1818, 'a son of Bungaree and Queen Gooseberry'. [19] About 1805 one of Bungaree's wives became the mother of the fair-skinned Ga-ouen-ren, called Dinah or Miss Diana, whose father was a European. [20]

In 1828 Bungaree and his clan moved their camp to the Governor's Domain (Sydney Domain) where he was seen naked and 'in the last stages of human infirmity'. [21] 'Bungaree is identified with Sydney and something ought to be done to make his few remaining days easier,' the writer commented. Affected by age, alcohol and malnutrition Bungaree suffered a serious illness that lingered for several months during 1830. He was admitted to the General Hospital and put on the rations.

Bungaree died at Garden Island on Wednesday 24 November 1830, 'in the midst of his own tribe and that of Darling Harbour, by all of whom he was greatly beloved'. He was buried 'beside his dead Queen' (Matora) in a wooden coffin at Rose Bay. [22]

A few months after his death, an image of Bungaree appeared on a painted board outside the King Bungaree public house in Clarence Street, Sydney.

A great number of black natives have congregated around the spot since its exhibition, who point with significant gestures at their old leader,

the Sydney Gazette reported. [23] [media]It is likely that the hotel sign was based on the striking pencil, ink and watercolour sketch, 'Bungaree King of Port Jackson Tribe Sydney' attributed to John Carmichael. This likeness, reproduced on the cover of King Bungaree (Kangaroo Press 1992) is in private hands.

While in Port Jackson early in 1824 René-Primavére Lesson, a surgeon and naturalist aboard the French corvette La Coquille, obtained a short vocabulary from Bungaree and examined his head. He wrote:

Bongarri … the wretched chief of the Sydney Cove tribe, showed us his skull quite shattered by numerous blows of a club which would have felled a strong animal. [24]

Notices of 'Donations to the Australian Museum' in College Street, Sydney, were regularly inserted in the Sydney Morning Herald during the nineteenth century. The entry '… skull of "King Bungaree," an Aboriginal of New South Wales' appeared among items received 'during November, 1857' on page 8 in the Herald for Wednesday 9 December 1857.

According to a spokesman for the Australian Museum, 'the Museum has no record of receiving the skull and certainly does not have it in its collection'. [25]

If Bungaree's skull was lodged in the museum in 1857 it would mean that his body had been dug up from the grave in which he was buried 27 years earlier at Rose Bay and decapitated.

It is possible that the 'donated' skull might have been that of Bungaree's eldest son Bowen Bungaree of Pittwater, who succeeded his father and wore his gorget. Bowen died in Sydney aged about 56 in 1853. [26]

Bungaree's second son Toby, Tobin or Joe was satirically called 'Toby Prince of Broken Bay' when he was put in the stocks for drunkenness in Sydney in 1837. [27] He seems to have died in Sydney in 1842.[28]

But the skull is missing. One possibility is that it might have been acquired in 1858 when the Austrian scientific expedition from the ship Novara exchanged artefacts and skeletal remains with the Australian Museum in Sydney.

On 1 December 1858 Dr Karl Scherzer from the Novara was taken from Kogarah to the Georges River by Edward Smith Hill, a curator at the Australian Museum seeking to unearth the remains of an Aboriginal man named Towwaa or Tow-weiry, better known as 'Tom Ugly'. His remains were too decomposed, so the scientists dug up the skull of a man named Micky or Sarannu. [29]

Scherzer, who first visited the Australian Museum in November 1858, wished to expand his collection of 'craniological specimens' to take back to Vienna. It is possible that the skull of Bungaree is now in the Novara Collection, in the History Collection at the Academy of Science in Vienna, Austria.

References

KV Smith, King Bungaree: A Sydney Aborigine meets the great South Pacific Explorers, 1799–1830, Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst NSW, 1992

Notes

[1] 'Bungaree, A Native of New South Wales', 1826, Augustus Earle, Oil, Rex Nan Kivell Collection, National Library of Australia, Canberra

[2] William Shakespeare, Twelfth Night, Act 111, Scene 1; Geoffrey Dutton, White on Black: The Australian Aborigine portrayed in art, Macmillan, South Melbourne, 1974, pp 28–31

[3] Sydney Gazette, 23 December 1804, pp 2–3

[4] Ship's muster, HMS Reliance, Monthly Book, Adm. 36/13398, National Archives, London

[5] Matthew Flinders, A Voyage to Terra Australis, W Nicol, London, 1814, p cxciv

[6] Dr John Harris to Governor PG King, 25 June 1801, King Family Papers, vol 8, Further Papers, 1775–1806, MS A10980-2, State Library of NSW, Mitchell Library

[7] Lieutenant Charles Menzies to Governor PG King, King's Town, 1 July 1804, Historical Records of Australia, vol V, pp 415–16

[8] Menzies to King, 5 October 1804, Historical Records of Australia, vol V, p 423

[9] 'Mut-tau-ra - - - The small snapper', LE Threlkeld, An Australian Grammar … of the language, as spoken by the Aborigines, in the vicinity of Hunter's River, Lake Macquarie, &c. New South Wales, Sydney 1834, p 86

[10] KV Smith, Eora Clans: A history of Indigenous social organisation in coastal Sydney, 1770–1890, 2004, pp 1–30; Jim Wafer and Amanda Lissarrague, A handbook of Aboriginal languages of New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory, Muurrbay, Nambucca Heads, 2008, pp 142–45 and 163

[11] Glynn Barratt, The Russians at Port Jackson, 1814–1822, Australian Institute of Studies, Canberra, 1981, p 34

[12] Phillip Parker King, Narrative of a Survey of the Intertropical and Western Coasts of Australia, John Murray, London, 1872, p 2

[13] Allan Cunningham, quoted in Ida Lee, Early Explorers in Australia, Methuen & Co, London, 1925, p 391

[14] Macquarie to Bathurst, 8 October 1814, Historical Records of Australia, vol 8, pp 367–70

[15] The Australian, 4 January 1828, p 3

[16] Macquarie, Journal, 11 February 1822, MS A774, State Library of NSW, Mitchell Library

[17] KV Smith, 'Gooseberry, Cora (c1777–1852)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Supplementary Volume, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2005, p 148; KV Smith, 'Moorooboora's Daughter', NLA News, vol XV1, no 9, National Library of Australia, Canberra, June 2006

[18] Anon [John Lang], 'Bungaree, King of the Blacks', in Charles Dickens (ed), All the Year Round, London, vol 1,no 4, May 1859

[19] JF Mann, Sydney Morning Herald, 22 June 1900, p 7

[20] Ga-ouen-ren, 1820, Pavel Mikhailov, watercolour, R292/14/211, Russian State Museum, St Petersburg; 'Miss Diana', Sydney Gazette, 22 January 1829, p 2

[21] Sydney Gazette, 7 July 1829, p 2

[22] 'Death of King Boongarie', Sydney Gazette, 27 November 1830, p 3

[23] Sydney Gazette, 16 July 1831

[24] René-Primavère Lesson, quoted in KV Smith, King Bungaree: A Sydney Aborigine meets the great South Pacific Explorers, 1799–1830, Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst NSW, 1992, p 127

[25] Brendan Atkins, email to Keith Vincent Smith 10 February 2011

[26] New South Wales Registry of Births Deaths & Marriages, Death V1853747 106/1853

[27] Sydney Gazette, 10 June 1837, p 3

[28] New South Wales Registry of Births Deaths & Marriages, Death V1842138 26B/1842.

[29] Dr Karl Scherzer, Diary, 1858, MSS A2635, pp 42-77, State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library

.