The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Berne, Dagmar

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Dagmar Berne

Dagmar Berne[media] was the first woman to enrol in medicine in Australia, at the University of Sydney in 1885, and faced considerable prejudice. She left to gain qualifications in London, Edinburgh and Dublin, before returning to Sydney and registering as a medical practitioner in 1895. Although her career was shortened by her premature death in 1900, Dr Berne pioneered women's medicine in Sydney, setting up a private practice, lecturing on health and nutrition, women's health and the achievements of women doctors and, in her last months, providing medical services to the township of Trundle.

Early life in Bega

Dagmar Berne was born Georgina Dagmar Berne at Denmark Lodge in Bega, New South Wales, on 16 November 1866, to Danish-born auctioneer Frederick Scoffwood Berne and his wife Georgina Kenyon (née Witton), a Hobart-born 'widow' who had, with her four children, moved to Bega to join her brother in 1864. [1] Family history research indicates Georgina was not in fact a widow, as her first husband William lived until 1882, but it has not been possible to ascertain whether she was divorced. There is every possibility she was a bigamist.

Frederick Berne was a prominent and ambitious local citizen. He was involved in public meetings, penned letters in The Bega Gazette, and lectured during his presidency of The Bega School of Arts, indicating a broad knowledge and interest in world affairs and scientific subjects. [2] Dagmar was therefore exposed to scientific discussions during her childhood, and her parents' modernist outlook and aspirational personalities may have influenced her to study medicine. Dagmar, the Berne's first child, was 'delicate' and as a baby she was kept alive on peach juice. She would suffer from pleurisy and recurring ill health her entire life. [3]

When Dagmar was nine, her father died in mysterious circumstances. Returning on horseback from an auction, carrying £500, his body was washed away in the Bega flood of 1875. [4] The cash was never located, but an empty money-belt and the remains of a foot in a riding boot were found weeks later. [5] According to members of the Bega Valley Historical Society, the local boot maker identified the boot as Frederick Berne's.

Childhood education in Sydney

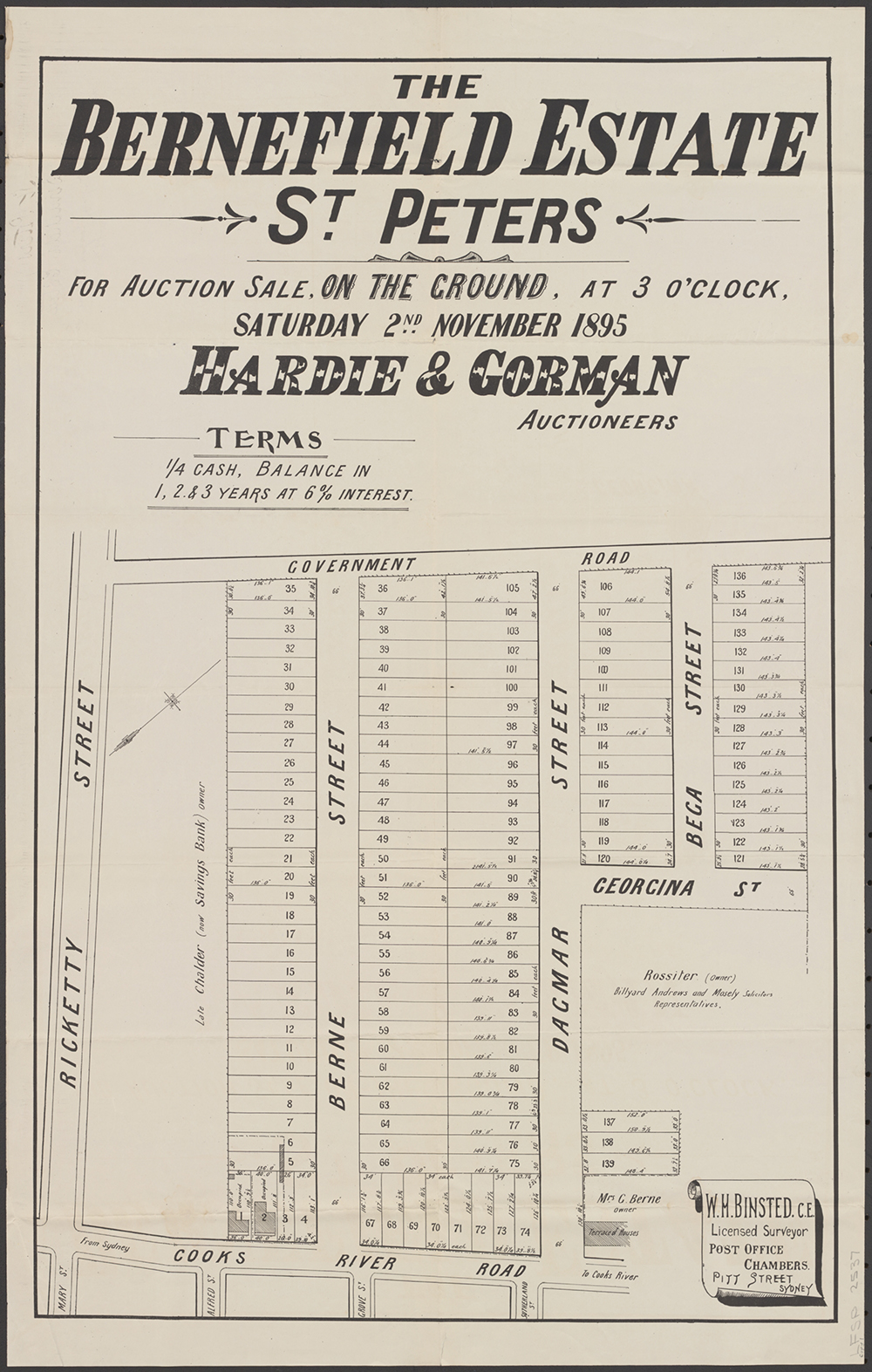

[media]Georgina Berne married builder Ephraim Stenteford in 1876 and moved with him and her family, which had grown to seven children, to Lancefield House, on what was then Cooks River Road, in St Peters. This relationship produced a child but then dissolved, and Georgina reverted to the name Berne and renamed the property Bernefield. Twenty years later, when Georgina subdivided Bernefield, she honoured her marriage with Frederick by calling the streets of the 'Bernefield Estate' Bega, Georgina, Berne, and Dagmar. [6]

Dagmar Berne and her younger siblings attended Newtown Superior Public School. In 1882, the teenage Berne boarded at the exclusive Springfield Ladies' College in Darlinghurst where she was trained in female 'accomplishments.' These did not include science subjects, which were not taught at girls' schools at this time. [7] Berne was unhappy during her one term of boarding and believed the fees were too high for the amount of useful learning she was receiving.

Matriculation and Arts at the University of Sydney

Berne requested private tuition in chemistry at the University of Sydney to assist her in passing the Senior Public Examination to enter the Faculty of Arts, which had just opened its doors to women students. [8] Believing she had been unsuccessful in the examination, Berne and her younger sister Florence planned a school at St Peters, until Berne learned she had matriculated and was eligible to enter the University of Sydney. [9]

Dagmar Berne entered the Faculty of Arts in 1884 and successfully completed her first year, studying Latin, French, Euclid, Algebra, Trigonometry, Arithmetic, Chemistry, Physics and English. [10]

The first woman to enter medicine in Australia

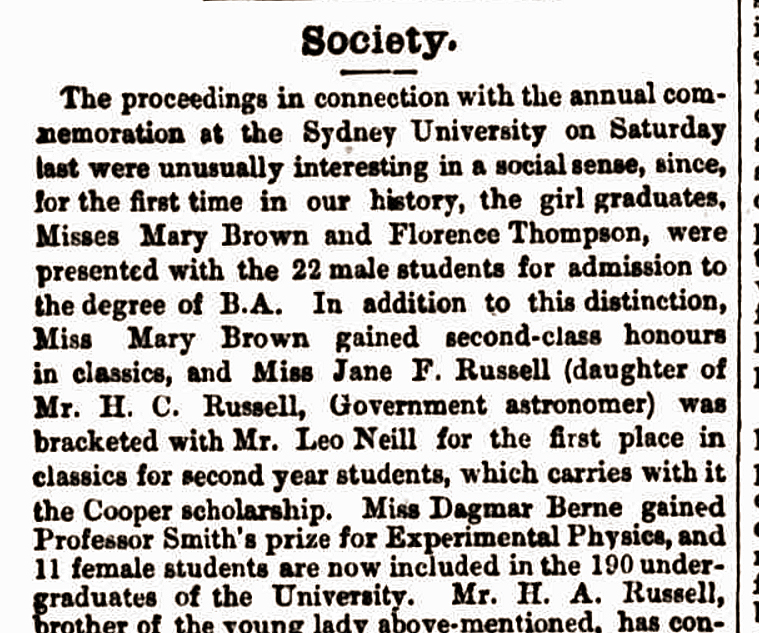

[media]In 1885, the University of Sydney decided to allow women students to study medicine, if they had completed the first year of arts. Berne was the first and only woman to enrol, becoming part of the third intake, of 15 medical students, in 1885. [11]

Dean of Medicine (Sir) Professor Thomas Peter Anderson Stuart and Vice-Chancellor (Sir) Henry Normand MacLaurin expressed opposition to women entering the faculty. Anderson Stuart said:

… the proper place for women is the home, and the proper function for a woman is to be a man's wife, and for women to be the mothers of our future generations … I have come to the conclusion that, within certain limits, they have played a useful part in medical life; but there are limits … I thought they would be much better employed if they got a nice frock and a nice man … while there is a place for a certain number of women in medicine, there are certain limitations of usefulness, and they will never, in my opinion, take the place, or be equal to men in general medical work. [12]

MacLaurin claimed that no woman would graduate in medicine whilst he was Vice-Chancellor. [13]

[media]Berne failed the First Professional Examinations in her first year of Medicine (II) in 1885, although she had won Professor John Smith's Prize for Experimental Physics, an annual book prize awarded to the most distinguished student at the Class Examination Viva Voce in Experimental Physics. [14] Her failure is surprising, suggesting open discrimination and a hostile learning environment. Berne repeated the year and then passed in 1886. She entered Medicine III in 1887 and Medicine IV the following year but failed the Second Professional Examinations of 1888. She was still studying Medicine IV in 1889 and passed the first two sections of her Second Professional Examinations, but failed Pathology and Materia Medica. She was allowed to take deferred examinations in these subjects in March 1890, but failed again. [15]

A portrait of Dagmar Berne

[media]Berne has been described as a natural, sensitive, shy woman with a serious and capable mind, who disliked bigotry, duplicity and shallowness. [16] Photographs taken during her days at the University of Sydney in the 1880s depict a determined young woman with light haircut short and boyish, with curls about her fringe.

Berne's male medical student contemporaries in the 1880s admired her complete concentration and immersion in her studies, with Sydney physician Dr Cecil Purser observing: 'a reserved woman, with plenty of intelligence and no small industry.' Sydney physician, lecturer and family friend Dr Robert Scot Skirving described: 'a quiet, friendly sensible girl – and no fool.' [17]

In spite of the demanding medical curriculum and unstable pulmonary health Berne was elected one of four office bearers of the University's Ladies Tennis Club and was a member of the University Musical Society. [18]

The London School of Medicine for Women

Berne met pioneer British woman physician Elizabeth Garrett Anderson during her lecture on 'Education' for women and girls, which was delivered at the Sydney School of Arts in April 1885. [19] Garrett Anderson had experienced prejudice as a female medical student, and the two women discussed the possibility of Berne completing her studies at the London School of Medicine for Women, where Garrett Anderson was Dean.

Dagmar Berne was fortunate to have an independent income and the moral support of her family. Confronted with the impossibility of passing medicine at Sydney University, she prepared to leave the country. Berne farewelled Anderson Stuart before her Sydney departure – he attempted to dissuade her, patting her on the head and telling her she was 'too nice a girl for that sort of thing.' [20] Berne and her sister Florence sailed to London together on RMS Austral on 19 April 1890. [21]

Berne entered The London School of Medicine for Women, as student 282, in the winter session of 1890. [22] Her teachers were Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and (Dame) Dr Mary Scharlieb, and physicians from the neighbouring Royal Free Hospital, where women medical students received clinical training. [23] Berne also worked at Garrett Anderson's all women's service, The New Hospital for Women, in Euston Road. [24] Florence, meanwhile, trained as a schoolteacher at the University of London's University Institute, Euston Road. [25]

The sisters boarded with an English family in a terraced house in St Pancras. [26] It was damp, and Dagmar suffered from pneumonia and pleurisy. Robert Scot Skirving unexpectedly met her at York Station during these years, and wrote later that she looked 'worn and rather frail', and rose from her bed to attend examinations, despite active pleurisy. Scot Skirving alluded to Berne having a romance with an English doctor, but it seems this relationship did not continue. [27] Berne never married or had children.

LSA, the Scottish Triple and postgraduate study

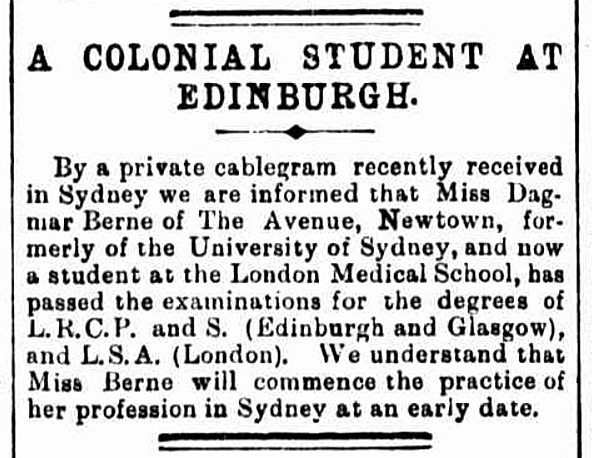

[media]Despite ongoing health problems and the loss of the Berne family fortune in the Bank Crash of the early 1890s, Berne gained the Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries (LSA) in London in 1891. She then relocated to Edinburgh. [28] In 1893 she gained the Scottish Triple: The Licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (LRCS), the Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (LRCP), and the Licentiate of the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow (LFPS). [29]

During 1893 she was appointed Clinical Assistant at the North Eastern Fever Hospital in South Tottenham [30] and assisted (Dame) Dr Mary Scharlieb to write a medical book, possibly 'A Woman's Words to Women on the Care of their Health in England and India', published 1895. [31]

In 1894 Berne travelled to Ireland for postgraduate study in midwifery at The Rotunda Hospital, Dublin. She received a glowing character reference from the Senior Assessment Master:

… she displayed marked aptitude for the work … and has a knowledge of the subject far above that held by most physicians, and I have no doubt, when I consider the rapid progress she made, will in the future prove herself a distinguished alumnus of the Rotunda, Dublin. [32]

Registration with New South Wales Medical Board

Dr Berne returned to Sydney in December 1894, and on 9 January 1895 was registered with the Medical Board of New South Wales. [33] She was the fourth Australian woman to do so after doctors Frances May Dick, Grace Fairley Robinson and Iza Frances Josephine Coghlan. [34] The Singleton Argus reported her Sydney professors 'claimed her on her return with London, Dublin, and Edinburgh certificates, as an honour to the Sydney University.' [35] The acute irony of this behaviour would have been keenly felt by Berne, although it suggests an increasing tolerance of women medical students, who by that stage were seeking entrance to the University of Sydney in growing numbers. A photograph of Berne at this time depicts a self-assured professional medical woman sporting fashionable leg-of-mutton sleeves. The portrait of the doctor is decidedly feminine.

Despite her qualifications, and her membership of the New South Wales branch of the British Medical Association, Dr Berne was not permitted to work in general hospitals, or in the two major Sydney hospitals, Prince Alfred Hospital and Sydney Hospital, where male medical graduates were routinely employed. [36] This prohibition afflicted almost the whole of the first cohort of women medical graduates who applied for appointments in general hospitals in Sydney.

Berne agitated against this exclusion, with both words and actions. She came to believe female doctors were needed to care for the medical problems peculiar to women and recognised that their professional development could be advanced by establishing a hospital run by women for women in Sydney. Her views were shared by Louisa MacDonald, Principal of the Women's College at the University of Sydney, and Dr (Grace) Clara Stone, founder of the Queen Victoria Hospital for Women and Children. [37] Berne explained her ideas in an 1898 interview with the Brisbane Courier:

Concerning the admittance of medical women as residents in general hospitals, it has occurred to me that I might place before your readers a scheme which would probably meet the difficulty… by following the example set us by our medical sisters in London, who, excluded from the general hospitals, started some years ago a hospital of their own, known as 'The New Hospital for Women,' which is officered entirely by women, with the exception of a few men consultants? A hospital on these lines, while affording to medical women an opportunity for study, allows those women of the poorer classes who prefer it (and there are many such) to consult a woman doctor…the hospital could be started at a slight expense by renting a small house in a populous part of the city, and the venture, I feel sure, would prove successful. [38]

Berne's vision would not be realised until 1922, when doctors Lucy Gullett and Harriett Biffin established The New Hospital for Women and Children, later the Rachel Forster Hospital.

Lecturing in Sydney

Despite being excluded from general hospitals, Berne led a full professional life, and within months of her return to Sydney began lecturing publicly in preventive health at venues such as Sydney Town Hall, beginning in 1895 with topics such as 'Health and Beauty'. [39] Under the auspices of the Ladies' Sanitary Association, she addressed large audiences of working-class women in the poorer inner suburbs of Sydney, and the northern suburbs. Topics she addressed included anaemia, household remedies, 'Our Babies', the hereditary nature of conditions such as insanity and phthisis (pulmonary tuberculosis), and the nutrition necessary to bear and raise healthy children. She encouraged discussion at the end of each lecture and answered questions. [40] The Sydney Morning Herald covered her August 1897 lecture at Sydney Town Hall, 'Digestion and Indigestion', reporting there were not enough seats to hold her audience and disappointed women were turned away. The newspaper reported that Berne had, in 'plain simple language', explained the importance of cookery and good eating and told her audience that 'bad cooking and bad food were the causes of much domestic and national misery and disaster.' [41]

Berne was also affiliated with the St John Ambulance Association and was appointed lecturer to their city ladies' class in 1896, lecturing on first aid, home nursing and hygiene at St James Hall in Sydney. [42]

That same year Berne also addressed her local branch of the Womanhood Suffrage League, at the Petersham Town Hall. Her speech, 'A Group of Noble Women', appraised the lives and careers of medical women such as Florence Nightingale, Dr Elizabeth Blackwell, Mrs Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Dr Sophia Jex-Blake and the pioneering work of The London School of Medicine for Women. [43] Berne was also involved with public meetings in connection with the Kindergarten Union of New South Wales. [44] Berne's affiliation with these pioneering feminist organizations, and the platforms she received, indicate her status amongst politicised women in both working and middle-class communities in Sydney, and also within the medical world of New South Wales.

Private practice in Macquarie Street Sydney

As well as public speaking engagements, Berne ran a private practice, sharing her rooms with two dentists. In 1896 she opened her practice in Epsom House, 219 Macquarie Street, then moved to 181 Macquarie Street in 1897–98. [45] Women doctors struggled to build private practices, as they were seen as oddities, and building a patient base took time, but it was necessary, given the exclusion of women doctors from general hospitals. While Berne established herself in Sydney, she lived in the Victorian filigree terraces Cyrus and Arthurville in L'Avenue Park, Newtown (now Warren Ball Avenue). [46]

Honorary medical work in women's health

Berne was also devoted to the cause of improving the lives of underprivileged women and girls in Sydney, working with them in the lower dock area of Woolloomooloo, for little or no fees. [47] It is possible this came about through her friendship with Jane Foss Russell (Barff) and her association with the Sydney University Women's Society, whose members served at the Woolloomooloo Girls' Club, Harrington Street Night School for Girls, and The Newington Asylum for Aged Women, at Parramatta. [48] Berne also delivered food and hygiene lectures to The Working and Factory Girls Club. [49] Berne's affiliation with these philanthropic women's groups suggest her beliefs aligned with those of pioneering feminist organisations in 1890s Sydney.

The Stanmore Lady Wheelers

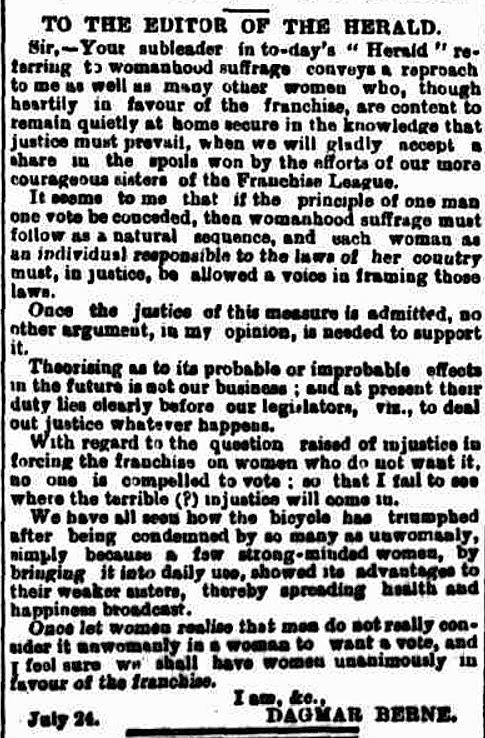

[media]Berne did not spend all her days working. She was an advocate of women's cycling, possibly influenced by her mentor Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, who was vice-president of the South Lambeth Tricycling Club. [50] In 1898, Berne became the vice-president of the Stanmore Lady Wheelers, a Sydney women's bicycle club formed and captained by wheelwoman Sarah Maddock, and within a year had become its president. [51] The popular social and touring club met regularly, bicycling to beauty spots such as Narrabeen lagoon, Cabarita, Sandringham, Penrith and Nowra. [52] In 1900, Berne wrote to The Sydney Morning Herald, championing the bicycle for women:

We have all seen how the bicycle has triumphed after being condemned by so many as unwomanly, simply because a few strong-minded women, by bringing it into daily use, showed the advantages to their weaker sisters, thereby spreading health and happiness broader. [53]

'Seeking the cure' in Springwood

By 1898, Berne's health was failing; she had a persistent cough and her body was wasting. At the insistence of her sister Eugenie, she sought medical advice and was diagnosed with advanced tuberculosis. She relinquished her medical work in Sydney and moved to Springwood, in the Blue Mountains, which had an elevated climate, renowned for its health-giving properties. Florence Berne was also principal of the Springwood Ladies College. Dagmar lived at the college, where the curriculum, rich in physical culture, calisthenics and outdoor games such as golf and tennis, reflected the exhortations of Dagmar Berne and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson that women should lead lives full of physical activity. [54]

[media]Berne participated in the life of this school and the small town, providing hygiene lectures to the girls and evening fundraising lectures on 'Health and Beauty' and 'Medical Women, Past and Present.' [55] She was also appointed vice-president of the Springwood Institute, a Debating and Social Club. [56] She did not lose her interest in Sydney feminism, and maintained a subscription to household women's journal The Dawn, printed by the famous suffragist Louisa Lawson. [57]

Last days in Trundle

By January 1900 Berne's pulmonary health had worsened and she moved to the drier and warmer township of Trundle, in western New South Wales. Trundle needed a doctor, and, despite her failing health, Berne conducted a private practice, initially from the property of family friends, Yarrabundie Station, then at professional rooms at the southern end of the Trundle Hotel. [58] Newspaper articles of the time suggest Berne was well loved and respected by the people of Trundle, and she probably enjoyed a higher social status in this town than she had in her previous life. [59] Berne expressed particular concern with the wellbeing of women after childbirth, insisting they receive adequate rest away from the demands of their household, which was a belief ahead of her time. [60] She regularly offered her services for little or no charge, and was remembered by a Trundle resident, Mrs Long, as:

… very conscientious and capable, and everyone in Trundle loved and respected her, for she was so kind and took such a personal interest in all her patients. The doctor always adored children and was wonderful with them … she regarded her practice as a work of love, not as a professional necessity. [61]

On the night of her death, 22 August 1900, Berne treated a man who injured himself with broken glass at the Trundle Hotel, [62] although she was so frail that 'she could hardly shake a bottle of medicine.' [63] She haemorrhaged and died of pulmonary phthisis and exhaustion in the hotel at midnight that evening. Her death was noted in The Sydney Morning Herald. [64]

Dagmar Berne was laid to rest in the Trundle General Cemetery. In 1901, Catholic patients donated a pair of bronze altar vases to the Roman Catholic Church of St Michael's at Trundle, which are inscribed 'In Loving Memory of Dagmar Berne, Licentiate Royal College Physicians and Surgeons'. In 1909, Berne's mother moved Dagmar's body to Waverley Cemetery in Sydney, although other members of the Berne family believed she should rest with the people of Trundle. [65]

Establishment of The Dagmar Berne Prize

Berne had owned an acre of land in Bega that was sold when probate was granted on her estate in 1915. [66] Soon after, her mother Georgina presented funds to the University of Sydney to establish a memorial to her daughter. The Dagmar Berne Prize was created in 1917 and was for many years awarded to the woman who gained the highest marks in the final year of Medicine. Dr Mona Ross (later Nelson) was the first woman to receive the prize in 1917, followed by her sister Dr Marjory Ross (later Thomas) in 1918. [67] In 2013, this monetary award was awarded annually to a candidate for the degrees of the Bachelor of Medicine and the Bachelor of Surgery for proficiency in the final barrier examinations. [68]

Dagmar Berne's life is honoured in Berne Place, Berne Crescent and Dagmar Berne Street in the Australian Capital Territory suburb of Macgregor. [69] In 2014, the Trundle Hotel website recorded her as the hotel's 'patron saint'. [70]

References

Vanessa Witton, 'An Improper Calling: a novel and exegesis based on the life of Australian pioneer doctor Dagmar Berne', Doctorate of Creative Arts thesis, School of Communication Arts, University of Western Sydney, 2007

Marjorie Hutton Neve, 'This Mad Folly': The History of Australia's Pioneer Women Doctors, (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1980)

Notes

[1] Vanessa Witton, 'Dagmar Berne's Story', Radius, Winter (2008): 30–31, accessed October 22, 2014, http://sydney.edu.au/senate/documents/History/Dagmar.pdf

[2] The Bega Gazette, June 6, 1868; The Bega Gazette, November 21, 1872. At the time of his death Fred Berne was president of the Bega School of Arts and employed in numerous working roles including magistrate and Commissioner for Affidavits in the district. See 'Business Directory', The Bega Gazette January 1, 1874

[3] Marjorie Hutton Neve, 'This Mad Folly': The History of Australia's Pioneer Women Doctors (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1980), 62. Neve states Berne's 1895 public lecture at Sydney Town Hall, 'Our Babies', suggests she may have suffered from phthisis (pulmonary tuberculosis) from birth.

[4] The Bega Gazette, April 2, 1874

[5] Margaret Evans, Voices from the South: Oral History, True Stories (Bega: M and N Evans Publishing, 1993), 2

[6] Hardie and Gorman Pty Ltd, 'The Bernefield Estate, St. Peters [cartographic material] : for auction sale on the ground, at 3 o'clock, Saturday 2nd November 1895', National Library of Australia, MAP Folder 157, LFSP 25, accessed October 15, 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.map–lfsp2537. By 2014 only Berne Street had survived the widening and reconfigurations of the Princes Highway

[7] M Little, 'Some Pioneer Medical Women of the University of Sydney', The Bulletin of the Post–Graduate Committee in Medicine, University of Sydney, 14, no 2 (May 1958), 27

[8] AJ Proust, ed, A Social and Cultural History of Medicine in NSW in the Nineteenth Century: Southern Tablelands and Monaro (Forrest, ACT: AJ Proust, 1999), 273–274

[9] Marjorie Hutton Neve, 'This Mad Folly': The History of Australia's Pioneer Women Doctors (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1980), 63

[10] Testimonial for Dagmar Berne, April 15 1890, Royal Free Archive Centre, London School of Medicine for Women Registry Records, Student Files, No 282, Dagmar Berne

[11] John Atherton Young, 'Second Act: The Medical School 1882–1889', in JA Young, AJ Sefton and N Webb, Centenary Book of the University of Sydney Faculty of Medicine (Sydney: Sydney University Press for The University of Sydney Faculty of Medicine, 1984), 137

[12] William Epps, Anderson Stuart, MD: physiologist, teacher, builder, organizer, citizen (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1922), 118

[13] Susanna De Vries, The Complete Book of Great Australian Women (Sydney: Harper Collins, 2003), 97

[14] The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, 7 May 1885, 6

[15] Nina Webb 'Women and the Medical School' in J A Young, A J Sefton and N Webb, Centenary Book of the University of Sydney Faculty of Medicine (Sydney: Sydney University Press for The University of Sydney Faculty of Medicine, 1984),218–220

[16] Marjorie Hutton Neve, 'This Mad Folly': The History of Australia's Pioneer Women Doctors (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1980), 63

[17] Marjorie Hutton Neve, 'This Mad Folly': The History of Australia's Pioneer Women Doctors (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1980), 64

[18] University of Sydney Calendar Archive 1887, accessed April 8, 2012, http://calendararchive.usyd.edu.au/Calendar/1887/1887.pdf. Evening News, May 17, 1889

[19] MK Doherty, The Life and Times of Royal Prince Alfred Hospital Sydney, Australia (Sydney: NSW College of Nursing, 1996), 136–137

[20] Marjorie Hutton Neve, 'This Mad Folly': The History of Australia's Pioneer Women Doctors (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1980), 66

[21] The Sydney Morning Herald, April 21, 1890

[22] London Metropolitan Archive, City of London, London School of Medicine for Women and Related Collections, Student Files 1874–1949, H72/SM/C/01/02, No 282, Dagmar Berne, Testimonial for Dagmar Berne, 15 April, 1890. These records were consulted when they were at the Royal Free Archive Centre.

[23] London Metropolitan Archive, City of London, London School of Medicine for Women and Related Collections, London School of Medicine for Women Annual Report, 1891. These records were consulted when they were at the Royal Free Archive Centre.

[24] Marjorie Hutton Neve, 'This Mad Folly': The History of Australia's Pioneer Women Doctors (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1980), 109

[25] In advertisements for Springwood Ladies College, Miss Fredericka (Florence) Berne stated she trained at London University and taught for several years in England. Illawarra Mercury, 1899, April 15, 3, accessed November 5, 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news–article132324564. She matriculated June 1891. Her name appears in the University of London General Register Part II, 15, in a list of undergraduates 31 March 1883–31 March 1893 who had not passed an examination by March 1899. Senate House Library Archives, University of London

[26] UK Census, 1891, RG 12/124, Pancras–London, UK Census Online, accessed November 5, 2014, http://www.freecen.org.uk/

[27] Robert Scot Skirving, 'Dagmar Berne: the First Woman Student in the Medical School of the University of Sydney', Medical Journal of Australia, 11 (no 14), October 1944, 407–409

[28] Archives of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons, Glasgow, 2006

[29] The Medical Directory (London: J and A Churchill, 1894), 98

[30] The Medical Directory (London: J and A Churchill, 1894), 98

[31] Marjorie Hutton Neve, 'This Mad Folly': The History of Australia's Pioneer Women Doctors (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1980), 68

[32] Marjorie Little and John WR Glenn, Character reference for Dagmar Berne and publication, 1894, National Library of Australia, NLA MS 3700

[33] State Records New South Wales, Medical Board of New South Wales, Album of Signatures, 19 June 1889 – 12 August 1896, NRS 9872

[34] Eric Hilder, One Hundred And Twenty Years of Medical Registration in New South Wales 1838-1958, compiled from the records of the New South Wales Medical Board by Eric Hilder (New South Wales: Department of Public Health, c1959), 106; Louella McCarthy, 'Finding a Space for Women: The British Medical Association and Women Doctors in Australia, 1880-1939', Medical History, 62 (No. 1), 2018, 97

[35] Singleton Argus, September 1, 1900, 4

[36] N Kyle, Her Natural Destiny: the Education of Women in New South Wales, (Kensingon: NSW University Press, 1986), 104. The first female medical graduates were not permitted to work in the New South Wales general hospital system until after Berne's death. See Louella McCarthy, Uncommon Practices: Medical Women in New South Wales 1885–1939 (PhD Thesis, University of New South Wales), 2001, 344. Very few of the first generations of women doctors in Australia joined the British Medical Association.

[37] Marjorie Hutton Neve, 'This Mad Folly': The History of Australia's Pioneer Women Doctors (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1980), 69, 109

[38] The Brisbane Courier, January 5, 1898, 2

[39] Lecture given at Waverley Presbyterian Church, Waverley, Sydney Morning Herald, May 25, 1895, 10

[40] The Sydney Morning Herald, July 30, 1895, 3; 'Sanitary Association', Evening News, July 30, 1895, accessed November 5, 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news–article109878097; Clarence and Richmond Examiner, May 4, 1897, 3; The Sydney Morning Herald, December 13, 1898, 6

[41] The Sydney Morning Herald, August 24, 1897; August 31, 1897, 3

[42] Sydney Morning Herald, May 6, 1896, 4; Sydney Morning Herald, August 26, 1896, 3; December 23, 1896

[43] Sydney Morning Herald, May 19, 1896

[44] Australian Town and Country Journal, 1 August, 1896, 35

[45] Sands Directory, 1896, 1897, 1898

[46] Sands Directory, 1895, 1898

[47] University of Sydney Archives, Dagmar Berne File, Mrs RS Hayter, Letter to Professor K J Cable, September 28, 1980

[48] U Bygott, 'Barff, Jane Foss (1863–1937)', Australian Dictionary of Biography: Supplementary Volume 1580–1980 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2005), 18–19, accessed April 8, 2007, http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/AS10024b.htm

[49] Working and Factory Girls Club, Report (Sydney: Wm Andrews and Co, 1898), 6

[50] E Crawford, Enterprising Women: The Garretts and their Circle (London: Francis Boutle Publishers, 2009), 310

[51] The Sydney Morning Herald, April 6, 1898, 4; March 6, 1899, 9

[52] The Sydney Morning Herald, September 14, 1897, 3; October 12, 1897, 6; October 8, 1898, 10; October 11, 1898, 6; March 22, 1899, 10

[53] The Sydney Morning Herald, July 26, 1900, 11

[54] E Crawford, Enterprising Women: The Garretts and their Circle (London: Francis Boutle Publishers, 2009), 47–48, 310. Even as early as 1868, Garrett Anderson's first lecture to the London Association of Schoolmistresses was 'The Physical Training of Girls.'

[55] Illawarra Mercury, April 15, 1899, 3, accessed 5 November 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news–article132324564

[56] The Nepean Times, February 18, 1899; June 24, 1899; September 9, 1899

[57] O Lawson, ed, The First Voice of Australian Feminism: Excerpts from Louisa Lawson's 'The Dawn', 1888–1895 (Brookvale: Simon and Schuster 1990), 17

[58] M Hutton Neve, 'This Mad Folly': The History of Australia's Pioneer Women Doctors (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1980), 68

[59] The Western Champion, August 24, 1900 and The Lachlander, August 31, 1900.

[60] M Hutton Neve, 'This Mad Folly': The History of Australia's Pioneer Women Doctors (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1980), 69

[61] M Hutton Neve, 'This Mad Folly': The History of Australia's Pioneer Women Doctors (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1980), 69

[62] JP Watts and Chas F Wright, The Story of Trundle: A Country Town and Its People (Parramatta: Macarthur Press, 1987), 88

[63] M Hutton Neve, 'This Mad Folly': The History of Australia's Pioneer Women Doctors (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1980), 69

[64] 'The late Dr Dagmar Berne', The Sydney Morning Herald, August 25, 1900, accessed October 15, 2014, http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/14332459

[65] M Hutton Neve, 'This Mad Folly': The History of Australia's Pioneer Women Doctors (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1980), 69

[66] State Records of New South Wales, Probate Jurisdiction, Georgina Dagmar Berne, April 20, 1915, Probate Packet No 68544

[67] MK Doherty The Life and Times of Royal Prince Alfred Hospital Sydney, Australia (Sydney: NSW College of Nursing, 1996), 137

[68] 'The University of Sydney List of All Prizes With Conditions', accessed October 16, 2014, http://sydney.edu.au/scholarships/docsprizes/medicine_prizes.pdf

[69] ACT Planning and Land Authority website, accessed August 12, 2012, http://www.actpla.act.gov.au/home

[70] 'Dr Dagmar Berne, Patron Saint of the Trundle Hotel', accessed October 16, 2014, http://www.trundlehotel.com.au/dagmar.html

.