The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Balmain Colliery

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Balmain Colliery

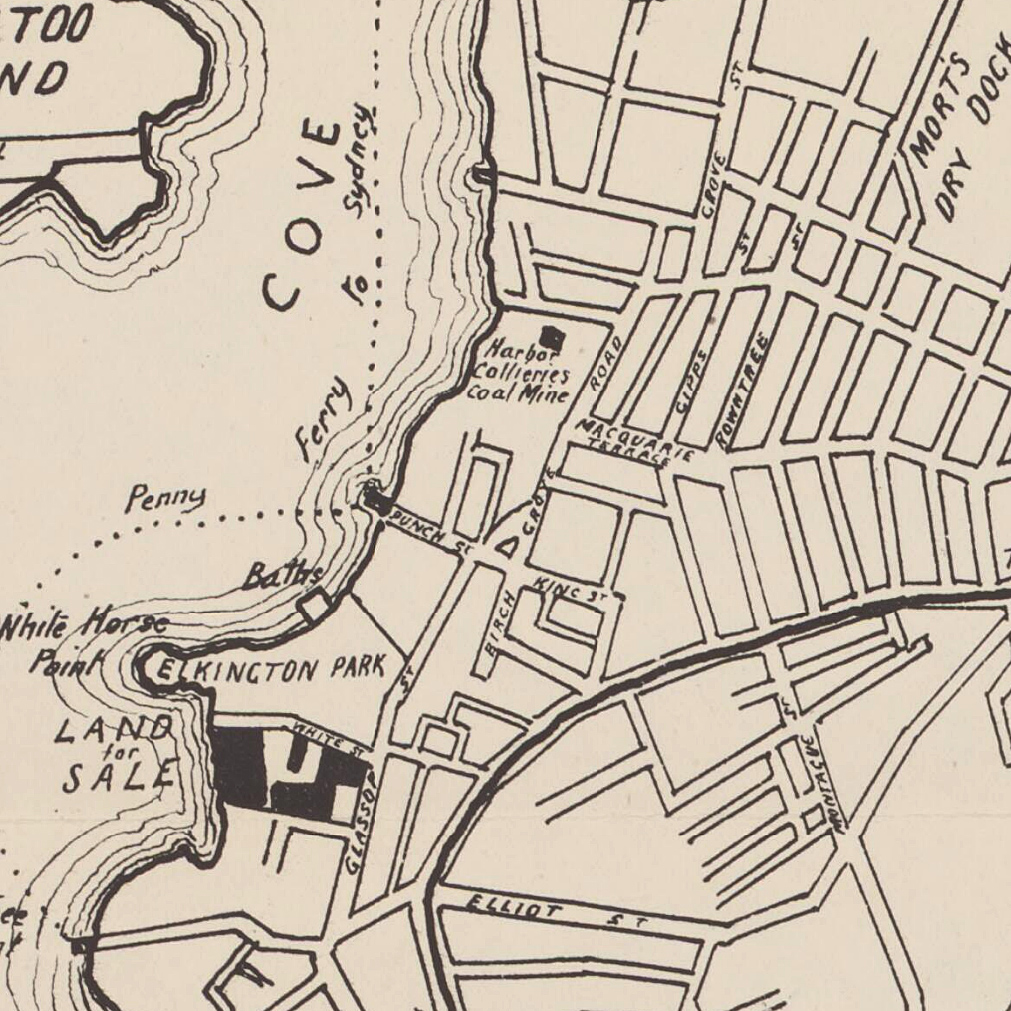

[media]Early European settlers found coal deposits north, south and west of the city and it was assumed that coal existed under Sydney as well. The cost of transporting coal from Newcastle provided an incentive for local exploration and bores were drilled in various places from the late 1870s. In the early 1890s the Sydney and Port Hacking Coal Company found a good seam at about 900 metres under Cremorne and sought a suitable site for surface workings. Local property owners objected to a coal mine in their backyards and the company settled on a site in Birchgrove bounded by Birchgrove Road, Water Street and the Birchgrove Public School. The Birchgrove area was already semi-industrial and another major employer was welcome.

The mine begins operation

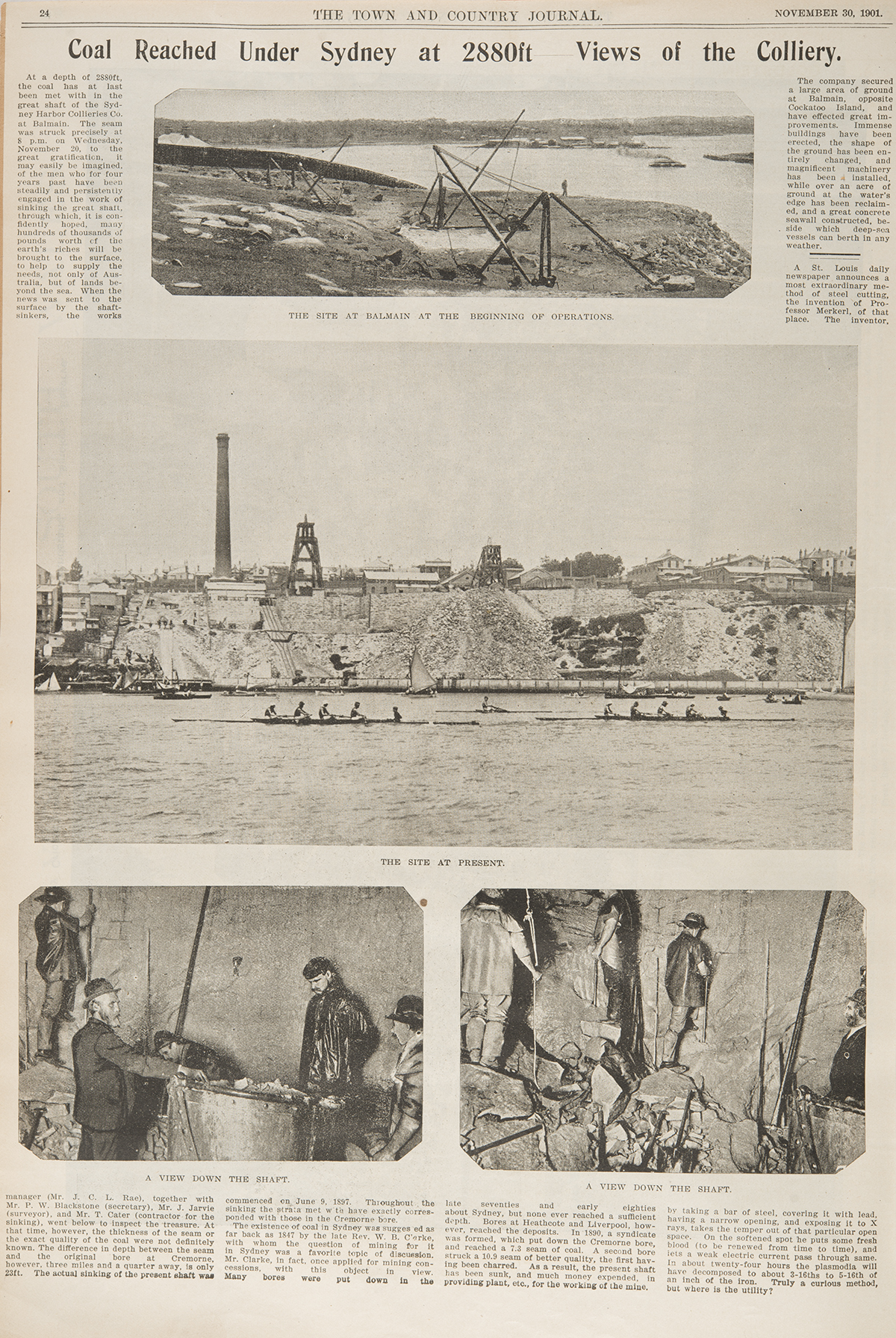

[media]The first shaft, named 'Birthday', was sunk between 1897 and 1902. Both this and the second shaft 'Jubilee' (both names commemorated Queen Victoria), were 5.5 metres in diameter and were fully lined with more than four million bricks. The sinking of the shafts did not always go smoothly. In 1900 five men being lowered in a bucket were tipped out 120 metres from the bottom and fell to their deaths. The sinkers went on lengthy strikes in 1902 and again in 1905.

[media]In 1902 the Birthday shaft struck coal at about 900 metres, making this the deepest coal mine in Australia, but it was a thin seam and the decision was made to extend the mine towards the more promising Cremorne bore which, being at the same depth, was assumed to be part of the same stratum of coal. This necessitated long drives in an easterly direction under the Balmain peninsula, but because the company held a licence only to mine under the harbour and public reserves, a special Act of Parliament ( Sydney Harbour Colliery Act, 1903) was needed to permit tunnelling under private land. [1]

Financial difficulties

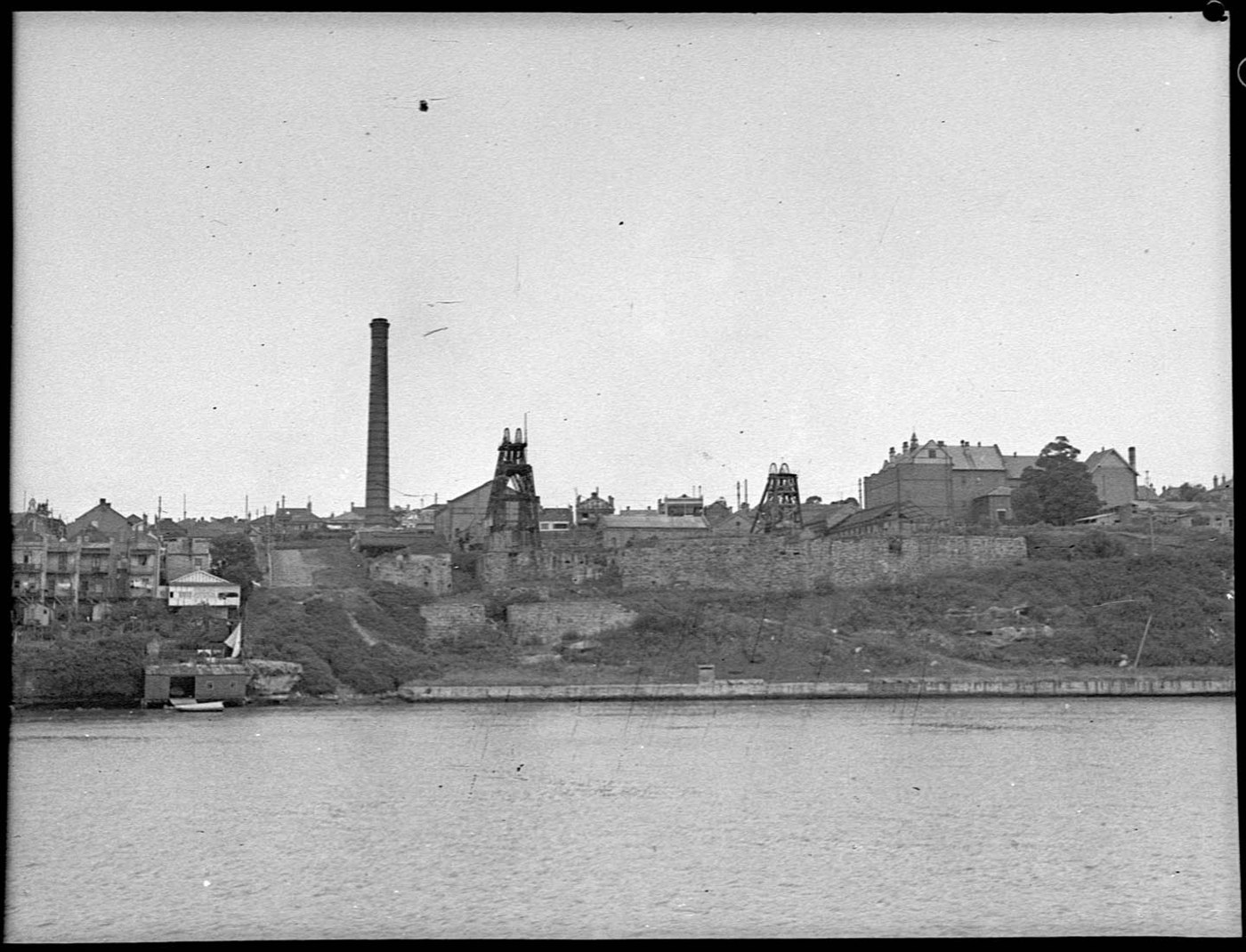

[media]The company faced heavy costs, not only for the extensive tunnelling required but also for the cost of surface machinery and buildings. It never managed to produce enough coal from the thin seam being worked to cover these capital costs and work ceased in 1915. The mine was reopened in 1924 but as the working face advanced further and further from the shafts, ventilation became a problem, along with the logistics of transporting men and coal long distances to and from the shafts. Rather than continuing to tunnel towards Cremorne, the workings spread out beneath the harbour between the Balmain peninsula, Balls Head and Goat Island. Finances continued to present a challenge and in 1928 the company was reorganised on a semi-cooperative basis. The miners became the Balmain Coal Contracting Company and took over the running of mining operations, selling their coal to the parent company, renamed Sydney Collieries Ltd. [2]

About 300 men were employed at any one time, working three shifts a day. Working conditions were unpleasant. Because the working face was about three kilometres from the shafts, ventilation was poor and the mine was very hot, humid and dusty. The roof tended to break away leaving dust and rubble blocking the narrow low-roofed passageways, which were also littered by the dung from the ponies that were used to pull coal wagons.

To make a profit wages and conditions had to be compromised, which caused conflict with the Miners' Federation. The union sought to preserve and enhance miners' conditions in other collieries and feared that Balmain was setting an undesirable precedent. Sydney Collieries finally went into liquidation in 1931. The mothers of children at the adjacent school must have been relieved; their children had returned home every afternoon with their clothes blackened from the coal dust, which blew into the playground with every breeze.

Methane gas production

In 1932 the mine was taken over by the Natural Gas & Oil Corporation which expected to find oil or methane gas if a bore was put down a further kilometre or so below the bottom of the mine shafts. In 1933 two men preparing to bore were fatally injured in an explosion. By 1937 the bore had reached about 1.5 kilometres but gas flow was weak and the expected reservoir of gas had not been found. In 1945 another explosion killed three men. During and after World War II the gas was compressed and sold as fuel, but gas flows diminished and production ceased in 1950. [3]

Reuse of the site

[media]In the 1950s the Birthday and Jubilee shafts were filled in with fly ash from the nearby White Bay Power Station and concrete seals placed on the shaft heads. In the half century since then, it is assumed that most of the workings have collapsed and filled with water. The site was used as an industrial depot for several decades and is now occupied by Hopetoun Quays, a development of more than a hundred townhouses. In 2014 Leichhardt Council placed a plaque at the corner of Water and River Streets, Birchgrove to mark the site and commemorate those who worked and died there.

References

Kennedy, Brian & Barbara. Sydney Tunnels. Kenthurst, NSW: Kangaroo Press, 1993.

NSW Department of Primary Industry. Balmain's own coal mine. Primefact 556 (February 2007). http://www.resourcesandenergy.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/109307/balmains-own-coal-mine.pdf.

Notes

[1] NSW Department of Primary Industry. ‘Balmain's own coal mine; Primefact 556 (February 2007), http://www.resourcesandenergy.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/109307/balmains-own-coal-mine.pdf

[2] NSW Department of Primary Industry. ‘Balmain's own coal mine; Primefact 556 (February 2007), http://www.resourcesandenergy.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/109307/balmains-own-coal-mine.pdf

[3] NSW Department of Primary Industry. ‘Balmain's own coal mine; Primefact 556 (February 2007), http://www.resourcesandenergy.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/109307/balmains-own-coal-mine.pdf

.