The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Aboriginal migration to Sydney since World War II

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Aboriginal migration to Sydney since World War II

The establishment of 'settled places' was central to the process of colonisation in Australia. This involved not only the vast physical and environmental changes wrought by European agriculture, architecture and engineering, but also the cultural changes associated with urbanisation. Much has been written about the Indigenous people of the Sydney region and their brutal treatment at the hands of European colonisers, who had little understanding of, or respect for, their traditional ways of life. [1] Less well documented are the patterns of Indigenous migration to Sydney from elsewhere. [2] This article will consider the experiences of Aboriginal people who moved to Sydney over the period from the mid-twentieth century, and the strategies they used to maintain communal bonds and cultural identities in response to pressures to assimilate. It will focus in particular on those who moved into suburban, mostly government, housing in western Sydney, and on the gender dimensions of urban relocation. The design of urban spaces and residential architecture together with the moral regulation that many experienced, especially those who were suburban tenants of the New South Wales Housing Commission, worked against the fulfilment of obligations to country and family.

Patterns of settlement

The precise patterns and extent of early and mid-twentieth century Indigenous migration to Sydney are difficult to determine. Much took place beneath the official radar, for until the 1960s Indigenous affairs were administered by the Aborigines Welfare Board on the basis that Aboriginal people who moved into towns and cities implicitly accepted an obligation to assimilate. For much of the twentieth century, Aboriginal people were not separately enumerated in the Commonwealth Census and although it is true that some were prepared to 'pass', and burn their bridges with Indigenous communities, [3] most were not. Those who continued to identify as Aboriginal sought out family and friends already living in the city. With the exception of Canberra, the patterns of Aboriginal movement to capital cities have largely been state and territory-based. As a result, the traditional country of most Aboriginal people living in Sydney is elsewhere in New South Wales.

Settlement trends reflected points of origin. For example, there are strong links between the Aboriginal community at La Perouse – originally a reserve to the city's south but eventually incorporated into the metropolitan area – and communities on the south coast. Most who moved to Sydney from the north coast or the state's west settled in the Redfern/Waterloo district, as did many of those who had been removed from their parents as children (the 'Stolen Generation') and were in search of family members. The Redfern area has long been (and still is) a meeting place, the symbolic heart of Aboriginal Sydney, going back to the days when Aboriginal people worked in the Eveleigh Railway workshops. [4] Anecdotal accounts indicate that between the wars the growth of the inner-city Indigenous population was gradual and largely prompted by the closure or reduction in size of various government reserves in rural New South Wales and the displacement of those who lived there. Urban migration increased in the 1940s and 1950s when labour shortages in Sydney meant Aboriginal people could earn higher wages there than were available in the bush. [5]

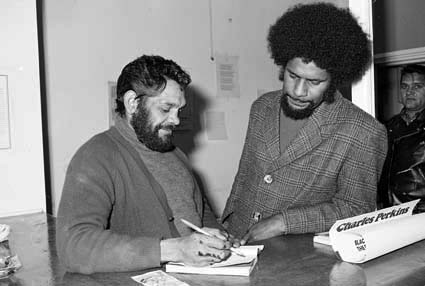

Chain migration created considerable overcrowding in the run-down inner-city housing that provided the only genuine rental option available to Aboriginal people. Racist letting practices by landlords and agents precluded those who identified and/or were identified as Indigenous from obtaining tenancies in better dwellings. The neighbourhoods in which Aboriginal people made their homes were often shared with members of the poor white working class – many from Irish Catholic backgrounds – and these districts were characterised by lively street culture and robust local social life. [6] In 1974, in response to plans by developer Ian Kiernan to redevelop the area around Eveleigh Street for private housing, Indigenous leaders, in coalition with local priests, approached the Whitlam federal government to set up an area of dedicated Aboriginal housing. [media]This led to a federal grant, the formation of the Aboriginal Housing Company and the purchase of the area that became known as The Block. [7] This became (and remains) the centre of Aboriginal community life and the site of numerous community and cultural facilities.

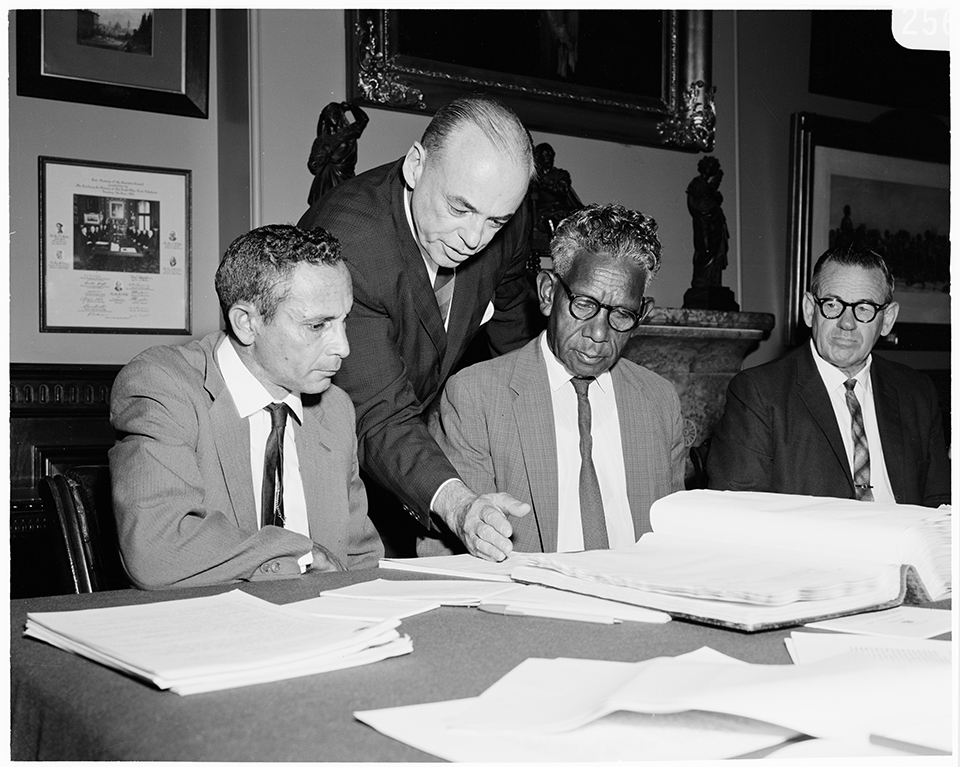

The shift in state policy towards urban integration occurred during the 1960s. Initially, in response to Indigenous population pressures in rural areas, the Aborigines Welfare Board sought to relocate 'worthy' Aboriginal families to suburban homes, some in country towns but many in Sydney. The organisation's senior officers hoped that families selected for such assistance would serve as a model for others to follow. Dawn magazine, the board's official publication, carried several 'success' stories. Alma Ridgeway brought her children from Burnt Bridge near Kempsey to live in Rozelle [8] and the family was shown happy and smiling and celebrating their good fortune. The mainstream press also covered the process. [media]In 1967, for example, the Sydney Morning Herald reported that Isabelle McLeod's family had moved from the south coast to Green Valley, near Liverpool, then a newly established government estate, and that she had become a pillar of the local community. [9] Such reports represented Aboriginal people as eager to move from humpy to house, from backwardness to modernity, and doing so without ambivalence. In reality the process was much more painful and complicated.

[media]In the late 1960s, the state Labor government wound up the Aborigines Welfare Board and allocated its responsibilities to mainstream government departments. It introduced the Housing for Aborigines (HFA) scheme under which the Housing Commission of New South Wales was required to provide a separate pool of predominantly suburban housing for Indigenous applicants, much of it located on large public estates in western Sydney, like those at Mount Druitt and Green Valley. [10] Although they had been entitled to apply for government housing since the Commission was established after World War II, very few Aboriginal people had succeeded in obtaining tenancies. Many were reluctant or unable to navigate the application process. Those who did had to endure the searching invigilation process required of all applicants, to determine if they would be respectable, neighbourly and capable of exemplifying what the Commission called 'civic pride'. Invariably, Aboriginal applicants were deemed unsuitable to be tenants. Although the pool of available housing increased dramatically with the introduction of HFA, applicants still had to endure the scrutiny of Commission gatekeepers in order to make it onto the waiting list. Only the elderly and those with school-age children were eligible to apply.

The introduction of the Indigenous public housing program had been heralded by its supporters in liberal integrationist terms, as symptomatic of a move away from the segregation and assimilation strategies of the past. However, the program's administration did not quite live up to these ideals and in many respects the practices of the Housing Commission resembled the social engineering exercised by the old Welfare Board. From an Aboriginal perspective, the exercise of colonial power had simply been shifted to a different agency. The primary function of the Commission was not social welfare or service provision but social engineering. It aimed to create déclassé respectable suburban communities. The structures and expectations associated with living in government suburban housing required much greater adjustment from Aboriginal people than from the white working class, for whom it was principally designed.

Adapting to urban life

How did they respond to the alienating and fragmenting forces of a modern city? Despite the experience of dislocation, most of those who came to Sydney from elsewhere in southeast Australia were long removed from Indigenous traditional life. Generations of Aboriginal people had experienced dispossession, dispersal and assimilation policies. However, as post-colonial theorists have argued, Indigenous cultures survive colonial dispossession and programs of assimilation. Conquered peoples are not simply remade in the image of the coloniser; they adapt to colonialism, interpreting and transforming the new symbolic structures through the lenses of their cultures. They accommodate coercive institutional pressures but rarely completely accept the moral influence of those authorities, whether state or religious, who seek to assimilate them. The principal challenge for those who moved to Sydney was to sustain their ongoing commitments to family and country despite the difficulties they confronted.

Many Aboriginal people were reluctant to embrace a conventional European sedentary existence. For example, the models of fixed residence and regular wage labour are central to the discourses of citizenship in Australia but are largely incompatible with Indigenous rhythms of life. Many of those who travelled from their home country to Sydney did not remain permanently. They returned to the bush for extended periods. This is still the case. For some, this was in order to take advantage of seasonal agricultural work, but more often it was family business and spiritual commitments to land that drew them back. Children were taken away from school [media]in the city in order to spend time in their home community, renewing and strengthening their Indigenous bonds. This disrupted employment patterns and it was more difficult for Aboriginal people without permanent addresses to deal with the state and to access mainstream support and services – education, health, social security and so on. [media]The long waiting list for government housing, for example, meant that there was a considerable time between lodging an application and being assessed for suitability for a Housing Commission dwelling. Many Aboriginal people had moved elsewhere by the time the Commission sought to contact them, and upon return had to reapply.

The spatial and architectural design of urban residential districts presented formidable cultural obstacles for Aboriginal people. Dwellings were usually built to accommodate nuclear families. Although this had also been true of the largely substandard houses constructed on reserves, such arrangements had not constrained the practice of extended family life in all-Indigenous places, as in the city. In the inner-city communities – not only in Redfern/Waterloo but also in areas like Newtown, Marrickville and Glebe – Aboriginal people learned to adapt their living places to accommodate many more people than they were originally designed for. A woman who grew up in Redfern in the 1950s recalled:

My mother was very good at making places for people to sleep. My father was a jack of all trades. So a place that was basically a two- or three-bedroom place was turned into a five-bedroom place. [11]

Suburban housing, in particular, was designed around the norm of the isolated nuclear family. [media]In Mount Druitt and Green Valley, where many of the mostly three-bedroom HFA houses were located, Indigenous tenancies were originally dispersed across wide areas on a 'salt and pepper' basis, in order to discourage the formation of Aboriginal solidarities (although areas of concentration were more common in south-western Sydney). The tenancy rules made it difficult for Aboriginal people to meet their obligations to host extended family members, often for extended periods. The Commission required that residents be limited to those listed as tenants, usually parents and children. There are numerous examples of Aboriginal tenants being threatened with eviction because unauthorised people were living with them in their houses. [12] The Commission was quick to respond punitively to the complaints of neighbours about loud and raucous outdoor gatherings, in gardens or the street, often involving extended family members. These confronted the expectations of privatised suburban tranquillity.

Many Aboriginal people who moved into new suburban estates found that the design of suburban lots and the moral expectations associated with living in such places were difficult to adjust to. For example, the tending of gardens, both front and back, signified respectability. Most of those who had lived on reserves had not been in the habit of exercising stewardship over, or feeling responsible for, the land immediately around their dwellings. Though tending and managing country was central to traditional culture, gardening was not. In the 1960s and 1970s conventional ideas about suburban gardens encouraged the planting of grass, exotic plants and flowers, but not drought-resistant natives. This separation of the suburban garden from the bush was foreign to those who had never lived in places that had been landscaped in the European style. New Aboriginal tenants in government houses from the 1960s generally experienced pressure from the New South Wales Housing Commission to trim their lawns and tend their gardens. Neglecting these tasks often led to criticism from neighbours, and even threats of eviction from officers of the Commission.

Perhaps a larger problem was associated with groups of footloose children. The division of public and private space proved to be particularly difficult for Aboriginal parents in suburban areas, especially those who had previously lived on reserves, where children experienced few constraints on their movement. The average size of Indigenous families was larger than the average for other Australian families, and it was difficult for parents, particularly single mothers, to confine large numbers of children to the boundaries of their suburban lot. Anger at children trespassing on neighbours' properties was a very common source of dispute among residents of Commission estates. [13]

Gender and suburban housing

There is substantial evidence that Aboriginal women were more eager to apply for government housing than their menfolk. As those primarily responsible for domestic labour and child-rearing, they had struggled in the substandard reserve housing, much of which had no internal running water and only the most basic of cooking facilities. Despite these difficulties, during the mid-twentieth-century assimilation era, the Welfare Board told them that to be deemed worthy of full citizenship, and to enjoy its benefits, Aboriginal people needed to demonstrate they were capable of respectable, clean and orderly domestic habits. Dawn magazine was filled with household hints designed to turn Aboriginal women into good housewives. Many recall the humiliation of the domestic inspections that were part of reserve and station life. [14] Those who lived with large families in cramped dwellings found it nearly impossible to present the appearance of domestic order. Yet for many, especially those who internalised the moral judgements about housework, the suburban bungalow offered a chance for stability and emancipation from the ceaseless toil of the reserve house or riverbank humpy. The fantasy of the modern housewife, ensconced in new suburban housing and freed from domestic drudgery by labour-saving appliances, was central to postwar images of the Australian way of life. Although this was principally a white Australian idyll, it had significant appeal to many Aboriginal women as well. Ruby Langford wrote of first seeing her HFA house in Green Valley:

My first glimpse of the house left me with a lump in my throat. When the kids asked why I was crying I said they were happy tears. [15]

However, for Aboriginal women to achieve this goal they had to get past the Commission gatekeepers, usually men, who were sent out to judge both the applicants' need for housing and the likelihood that they would be clean, quiet, morally respectable, good parents and neighbours.

[media]For many women, Commission housing provided a refuge from broken relationships and circumstances in which abuse was real or threatened. For example, in June 1970 a young Aboriginal woman applied for Commission housing, while living with her parents in Mount Druitt. Her relationship had broken down after her husband got drunk and fell asleep while responsible for caring for the couple's young children. In the argument that ensued he pulled a gun on her. The police were called, but he wasn't charged. The inspection report stated:

Would suggest further investigation to see how G's domestic problems sort themselves out before deciding whether she would be a suitable tenant.

Welfare considerations were not paramount in the Commission's evaluation of applicants for tenancies. Of the 3223 files of applicants for HFA housing, from the late 1960s to the early 1980s and covering all of New South Wales, 863, or just over a quarter, were from single mothers. In addition, the relationships of many women who applied jointly with their partners broke down soon after they moved into government housing. Many tenancy files contain notes from Commission officers describing reluctance and hostility from husbands and de facto spouses during the inspection process. Many men were apparently more inclined than women to remain in reserve housing or among their friends and relatives in the inner city. So in some respects the process of suburbanisation was gendered. The movement away from Aboriginal communities was often driven by women, some of whom were seeking to take their families away from cultures of addiction and violence.

Conclusion

Today the majority of Indigenous people in New South Wales live in cities or large towns and western Sydney accommodates the largest Aboriginal community in Australia. The demographic transformation of the Aboriginal population from predominantly rural to urban was encouraged by the provision of identified social housing (including housing now owned by Aboriginal organisations) in suburban areas, where before the 1960s there was virtually none. However, the establishment of inner-city communities preceded this suburbanisation. Such communities defied the official expectation that those who made the journey to the city would, by choice or circumstance, become assimilated. Indeed by struggling to sustain their connections to homelands and families, they helped to produce sacred Aboriginal places in the heart of Australia's largest city. The processes of living as Indigenous citizens, whether in inner or outer urban areas, or in private or public tenancies, involved resisting moral norms that were central to city life. [media]These included challenging conventional ideas about residence and way of life, adapting houses for large families, and redefining outdoor spaces in communal terms. However, it is important to recognise that urbanisation was also associated with cleavages within Aboriginal communities – between those who wished to identify as Aboriginal, and the minority whose dreams of social mobility led them to pass. In particular, public housing provided women, especially single mothers, with stability and the opportunity to escape the circumstances of poverty, struggle and varying degrees of patriarchal oppression that many encountered while living in Aboriginal communities.

References

K Anderson, 'Constructing Geographies: Race, Place and the Making of Sydney's Aboriginal Redfern' in P Jackson and J Penrose (eds), Constructions of Race, Place and Nation, University College London Press, London, 1993

H Goodall, Invasion to embassy: land in Aboriginal politics in New South Wales, 1770–1972, Allen & Unwin in association with Black Books, St Leonards NSW, 1996

M Hinkson, Aboriginal Sydney: A guide to important places of the past and present, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2001

J Kohen, The Darug and Their Neighbours: The Traditional Aboriginal Owners of the Sydney Region, Blacktown and District Historical Society, Sydney, 1993

R Langford, Don't Take Your Love to Town, Penguin, Ringwood Vic, 1988

G Morgan, Unsettled Places: Aboriginal People and Urbanisation in New South Wales, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2006

S Morgan, My Place, Fremantle Arts Centre Press, Fremantle WA, 1987

L Taksa, 'Pumping the Life-blood into Politics and Place': Labour Culture and the Eveleigh Railway Workshops ', Labour History, no 79, pp 11–34

Notes

[1] H Goodall, Invasion to embassy: land in Aboriginal politics in New South Wales, 1770–1972, Allen & Unwin in association with Black Books, St Leonards NSW, 1996; J Kohen, The Darug and Their Neighbours: The Traditional Aboriginal Owners of the Sydney Region, Blacktown and District Historical Society, Sydney, 1993

[2] G Morgan, Unsettled Places: Aboriginal People and Urbanisation in New South Wales, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2006

[3] A process perhaps best described in S Morgan, My Place, Fremantle Arts Centre Press, Fremantle WA, 1987, an autobiographical account of growing up in a 'passing' family in Perth

[4] L Taksa, 'Pumping the Life-blood into Politics and Place': Labour Culture and the Eveleigh Railway Workshops ', Labour History, no 79, pp 11–34

[5] G Morgan, Unsettled Places: Aboriginal People and Urbanisation in New South Wales, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2006, ch 3

[6] M Hinkson, Aboriginal Sydney: A guide to important places of the past and present, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2001

[7] K Anderson, 'Constructing Geographies: Race, Place and the Making of Sydney's Aboriginal Redfern' in P Jackson and J Penrose (eds), Constructions of Race, Place and Nation, University College London Press, London, 1993

[8] Dawn, December 1955, p 6, HYPERLINK "http://www1.aiatsis.gov.au/dawn/docs/v04/s12/8.pdf" http://www1.aiatsis.gov.au/dawn/docs/v04/s12/8.pdf, viewed 4 December 2008

[9] G Morgan, Unsettled Places: Aboriginal People and Urbanisation in New South Wales, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2006, pp 75–6

[10] G Morgan, Unsettled Places: Aboriginal People and Urbanisation in New South Wales, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2006, ch 4

[11] interview quoted in G Morgan, Unsettled Places: Aboriginal People and Urbanisation in New South Wales, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2006, p 110

[12] G Morgan, Unsettled Places: Aboriginal People and Urbanisation in New South Wales, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2006, ch 4

[13] G Morgan, Unsettled Places: Aboriginal People and Urbanisation in New South Wales, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2006, pp 92–4

[14] G Morgan, Unsettled Places: Aboriginal People and Urbanisation in New South Wales, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2006, ch 5

[15] R Langford, Don't Take Your Love to Town, Penguin, Ringwood Vic, 1988, pp 173–4

.